Better Behaved Behavioral Models

We often can’t rely on ourselves to act rationally (or prudently). We know this, but influential social science models have a bad habit of ignoring it. They need a more realistic role for “reason” in how our decisions and actions interact. We evolved to frequently act without “deciding.”

1. The widely used Rational Actor Model makes three assumptions: First, life is a stream of decisions, second we make them consciously (often calculatingly), and third, they lead us to act rationally.

2. That most self-improvement resolutions reliably fail (despite our consciously decided aims) is one of many demonstrations that those assumptions are all frequently false, is. Much of what we do isn’t consciously considered or calculated on the spot, and what we rationally know often doesn’t determine our actions.

3. The Rational Actor Model isn’t an action model; it’s a decision-model that ignores how we do much of what we do. It is fundamentally aspirational, under-empirical, and applies only in limited situations. Yet this “rationalist delusion” dominates economics and social policy.

4. Behavioral Economics—its name amusingly highlighting what’s been lacking—offers hope. Its discoveries (which we experience every day, but which un-behavioral economists typically ignore) include “cognitive biases” (assumed to be “systematic errors” in our “machinery of cognition”). This is progress, but it’s a near-reaching revolution (repairing the old rationalist clunker).

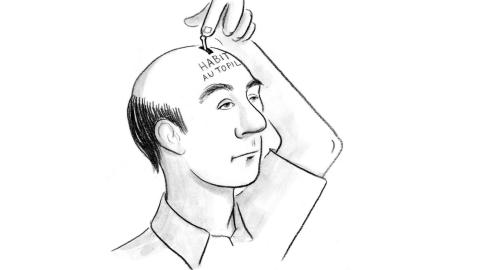

5. Better behavioral models should be, like us, habit driven. Our lives are often a stream of habitual actions (whose harvest we repeatedly reap on autopilot). We consciously decide only if that flow is interrupted. Thinking is expensive and reinventing cognitive or behavioral wheels is rarely productive, so we evolved to acquire second nature habits from others. Darwin said “much of the intelligent work done by man is due to imitation” not reason. We are habit-formers and habit-farmers.

6. Habits = behavioral tools enabling rapid action without costly conscious attention. Each habit can be modeled as a situational trigger with an action script. In triggering situations, they can be overruled, but only with conscious effort. Action scripts likely use rule of thumb style conditional logic-scripts, rather than cognitively unnatural numerical methods.

7. Habits can be rationally useful or irrationally unfit for a given situation. And cognitive biases could be bad cognitive habits—badly triggered action scripts—rather than built-in brain bugs. Especially since what is called rational, requires training.

8. We must be rational when habits are acquired, since later they will be repeated without deliberation. As Aristotle noted living well required “rational habits.”

Force of habit shapes our lives. Shouldn’t it also shape how our sciences model us? Especially those we build institutions on. Bring on the habitology (and habitonomics).

Illustration by Julia Suits, The New Yorker cartoonist & author of The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions