Nuclear Fear, Science, and Ideology

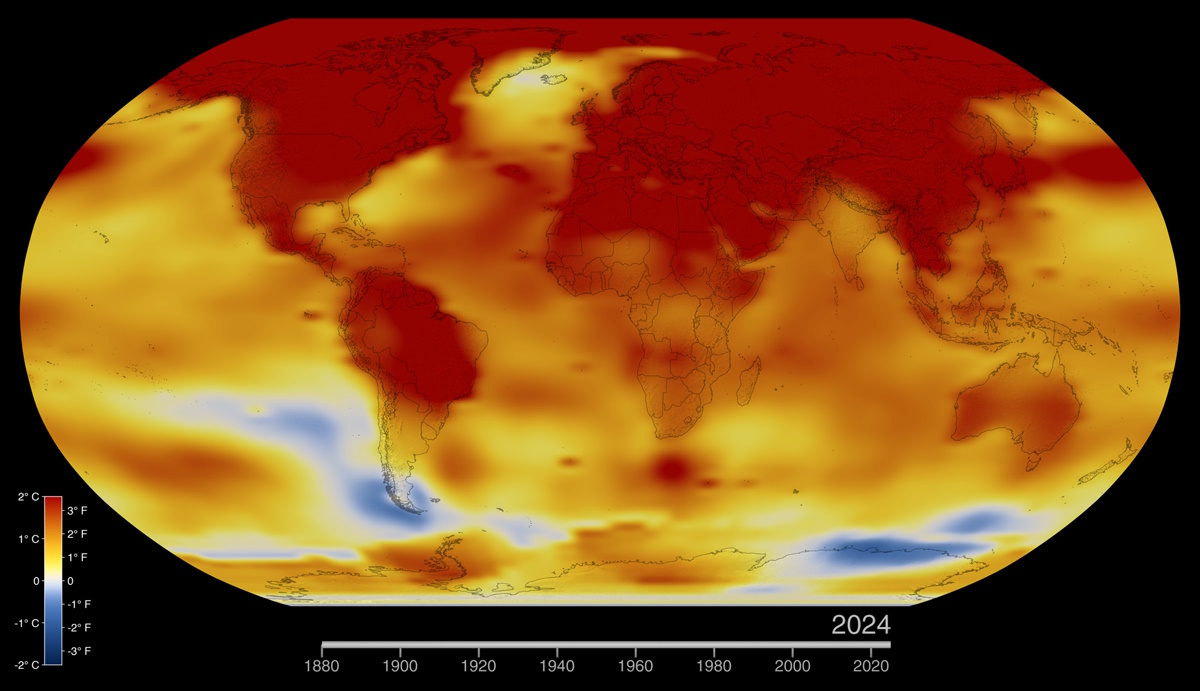

In a front-page story at today’s Washington Post, David Brown spotlights research on the comparative risks of nuclear and coal power. As Brown reviews, nuclear power is far less of a risk to public health than coal generation, and this difference is magnified when factoring in the health impacts of climate change. Yet despite the comparative advantages of nuclear power, both to human health and in tackling climate change, many liberal groups remain in strong opposition. In a guest post, risk communication expert and author David Ropeik reflects on the the role of ideology in shaping views of nuclear power and climate change. Both liberals and conservatives tend to deal with science-related information on the two topics in similar ways, argues Ropeik. Each tend to reject information that is contrary to their existing viewpoints— Matthew C. Nisbet.

The first glimmers of hope begin to shine from the nuclear crisis in Japan, but they will do little to brighten the views of some about nuclear power. As the disaster at Fukushima has shown, nuclear certainly has risks, as do all forms of energy. But the disaster has also reminded us that it’s really hard to get people to change their minds about a risk, once those minds have been made up. And closed mindedness isn’t the brightest, or safest, way to make the healthiest possible choices about how to stay safe.

As a TV reporter in Boston, I covered several nuclear power controversies. Seabrook. Pilgrim. Yankee Rowe. These were great stories…lead stories…because they involved possible public exposure to nuclear radiation, and everybody knows that’s really dangerous. My stories were full of ominous drama and alarm. But when I joined the Harvard School of Public Health and researched nuclear power for a chapter in a book, “RISK, a Practical Guide for Deciding What’s Really Safe and What’s Really Dangerous in the World Around You”, I was ashamed to learn how uninformed and misleading my alarmism had been. Ionizing radiation is indeed a carcinogen. But it’s not nearly as potent as most people fear.

Ninety thousand survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been followed for 66 years by epidemiologists from around the world and compared to normal cancer rates in Japan, only about 500 of those survivors have died because of the radiation. About two thirds of one percent. The radiation also caused birth defects in children born to women pregnant when they were exposed, but no long term genetic damage. These findings are widely accepted in the scientific community. Governments around the world base their radiation regulations on them.

But that evidence is rejected by people who have made up their minds about nuclear power. They reject the reassuring evidence from respected neutral organizations and substitute their own, from sources like Greenpeace or others that have a well-established anti-nuclear posture. Which is interesting, because this is just what many of those anti-nuclear activists accuse the conservative right of doing on climate change; denying the science, using only the facts that fit their pre-conceived views, quoting only the experts who agree with them. What they’re doing with nuclear power is sort of like complaining about people who argue against climate change by citing facts from closed-minded right wing science deniers like Senator James Inhofe or Rush Limbaugh, then turning around and doing the same thing.

Blogger Chris Mooney writes on Desmogblog “Are Liberals Science Deniers? Now’s a Good Time to Find Out.” He refers to the nuclear debate as ”…a natural experiment in the politicization of science,” and optimistically bets that anti-nuclear liberals will be more open minded and respectful of the scientific evidence than conservatives. And indeed some of his respondents, and comments elsewhere, come from self-identified liberals who are open to consideration of nuclear power.

But liberal inflexibility about nuclear power is still widespread. Peter Canellos of the Boston Globe writes about strident anti-nuke Helen Caldicott trying to “…brace up wobbly liberals who look to nuclear energy as a cure for global warming.” Writers responding to a blog I wrote for NPR, “Nuke-O-Noia Could be the Greatest Threat to Japan,” in which I suggested the health impacts of fear could do more harm than the radiation – as the UN found was the case after Chernobyl – said; “Do you need references to other studies that show different statistics for TMI and Chernobyl? I’m stunned.” Another commentator wrote: “Nuclear Propaganda Radio. I’m giving my financial support to Democracy Now,” a liberal radio program that’s avowedly anti-nuclear.

More thoughtful liberals maintain their anti-nuke positions by saying it’s unaffordable, or we haven’t figured out how to dispose of the waste, or that spending on nuclear denies economic support for renewables. Much of which is rooted in a fear of nuclear radiation that flies in the face of the biological facts. Nuclear radiation is dangerous, but not as much as those rooted fears believe. That puts the tradeoffs of nuclear power compared with other energy sources in a whole new light.

But the point here is not about nuclear power. The observation here is that our perception of risk is never a neutral unbiased view of the evidence. The psychology of how we perceive and respond to risk is an affective mix of facts and how those facts feel. And once we’ve made up our mind about a risk, Confirmation Bias takes over and we choose to believe the evidence that agrees with what we already believe. True liberals, non-wobbly liberals, are supposed to oppose nuclear power. Period. True conservatives, for some reason, are supposed to deny climate change. Period. Find the facts that fit. Toss out the inconvenient truths. Personally denigrate anyone who disagrees, because other views are not just a different way of looking at things. They’re a threat. These are litmus test issues for who gets to belong to the tribe, and who doesn’t.

That sort of thinking may be a deep seated part of how we perceive risk, but it’s risky in and of itself. Closed-mindedness is self-evidently dangerous. It may feel safe to steadfastly wave the tribal standard, but it’s surely a wobbly way to make decisions about energy policy, or any other risk, if we want to make the most informed and healthiest choices.

–Guest Post by David Ropeik, an Instructor at Harvard, consultant in risk perception and risk communication, former environment reporter in Boston, and author of the newly released, “How Risky Is It, Really? Why Our Fears Don’t Always Match the Facts.”