Halloween’s Media Myth: Did the War of the Worlds Lead to Mass Hysteria?

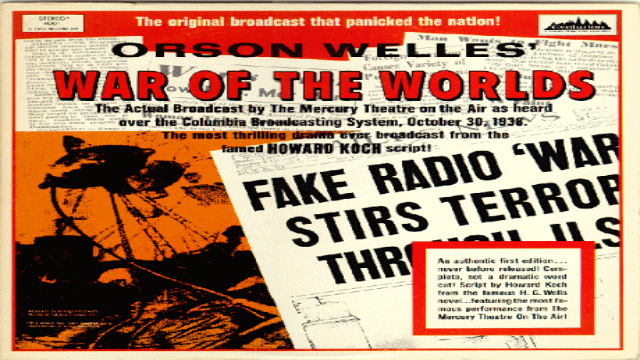

The War of the Worlds dramatization that aired October 30, 1938 has been called “the most famous radio show of all time.” It was a vivid, clever, fast-paced broadcast that told of an invasion of Earth by Martians wielding deadly heat rays.

The program was an adaptation of H.G. Welles’ famous 1898 science fiction work, The War of the Worlds, which was set in England. The 1938 radio dramatization was directed by 23-year-old Orson Welles, who placed ground zero of the Martian invasion in rural New Jersey, not far from Princeton.

Welles’ dramatization supposedly was so alarming—and so realistic in its use of simulated news bulletins telling of the alien attack—that listeners by the tens of thousands, or even the hundreds of thousands, were convulsed in panic and mass hysteria.

They fled their homes, jammed highways, overwhelmed telephone circuits, flocked to houses of worship, set about preparing defenses, and even contemplated suicide in the belief that the end of the world was at hand.

Or “so the media myth has it,” W. Joseph Campbell writes in Getting It Wrong, his new book that debunks 10 prominent media-driven myths. Getting It Wrong offers compelling evidence that the panic and mass hysteria so readily associated with The War of The Worlds program did not occur on anything approaching nationwide dimension.

While some Americans were frightened by what they heard, Campbell writes, “most listeners, overwhelmingly, were not: They recognized it for what it was—an imaginative and entertaining show on the night before Halloween.”

Getting It Wrong is Campbell’s fifth book, all of them published since 1998. Campbell is a full professor in the School of Communication at American University. Before entering journalism education, he was a newspaper reporter and wire service correspondent for 20 years, in a career that took him across North America to Europe, Asia, and West Africa.

Here he describes the media-driven myth of The War of the Worlds radio program and at the end of the interview you can watch a YouTube clip of Campbell discussing the case.—Matthew Nisbet

How do you define “media-driven myths”?

“Media-driven myths” are prominent stories about and/or by the news media that are widely believed and often retold but which, under scrutiny, prove to be apocryphal or wildly exaggerated. Media-driven myths are dubious tales masquerading as factual that often promote misleading interpretations of media power and influence.

They can be thought of as the “junk food of journalism.” They can be too good to resist, but they’re not terribly healthy, not terribly nutritious.

What drew your attention to the War of the Worlds as a possible example of a media myth? What were the claims about this event?

Like many media-driven myths, claims about the 1938 radio dramatization seemed too good, too delicious, to be true. Those claims, essentially, were that Americans by the tens of thousands—even the hundreds of thousands—were pitched into panic and mass hysteria by listening to the radio show.

But think about it: Tens of thousands? Even hundreds of thousands? That sounded to me quite unlikely and highly improbable. Especially given that mass panic is such a rare phenomenon.

As a historian and veteran journalist, how did you research this case?

I examined many sources, including dozens of news accounts published the day after The War of the Worlds program. And I found that those reports were largely anecdotal and emphasized breadth over depth. Close reading of contemporaneous news reports made clear that no persuasive case can be made that tens of thousands of Americans were convulsed in panic that night. As I write in Getting It Wrong,“U.S. newspapers reached indefensible conclusions that panic and mass hysteria prevailed in the aftermath of TheWar of the Worlds broadcast.”

I also scrutinized the research reported by Hadley Cantril, a Princeton University psychologist who studied public reaction to The War of the Worlds program and published his results in 1940 in The Invasion From Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic. Cantril’s work is sometimes regarded as a landmark in mass communication research. He estimated that at least 6 million people listened to the program that October night. Of those, at least 1.2 million were “frightened,” “disturbed,” or “excited” by what they heard. Cantril did not operationalize those terms which, in any case, are hardly synonymous with panicked or hysterical.

Cantril’s own calculations, then, indicated that most listeners were neither panic-stricken nor fear-struck. They presumably recognized and enjoyed the program for what it was—an entertaining and imaginative radio show which, by the way, aired on CBS in its regularly scheduled time slot of 8 to 9 p.m. on Sunday.

A couple of articles also were helpful in my research. They were a short article by Michael Socolow, and an essay by Robert E. Bartholomew, both of whom expressed skepticism that the program caused widespread panic.

In evaluating the War of the Worlds claims, what evidence led you to classify it as a media myth?

The anecdotal news reports simply did not rise to the level of nationwide panic and mass hysteria.

Had there been widespread panic and mass hysteria that night, newspapers for daysand evenweeks afterward would have been expected to have published details about the upheaval and its repercussions. But as it was, newspapers dropped the story after only a day or two.

Moreover, there were no deaths, serious injuries, or even suicides associated with the program. Had there been widespread panic and hysteria, surely many people would have been badly injured and even killed in the resulting tumult.

Cantril and other have pointed to the surge in the volume of telephone calls that night as evidence of panic and hysteria. But call volume scarcely is a revealing measure of panicked reactions. It’s true that calls surged in many parts of the country, especially in metropolitan New York and New Jersey, but many of the callers were seeking confirmation or clarification, which is an altogether rational response. Also, newspapers reported that some callers volunteered their services to confront the invaders. These callers may have been confused, but they were necessarily panic-stricken.

And more than a few callers called to compliment CBS and to urge the network to rebroadcast the show.

Of everything you have read and evaluated about this case, what did you find the most interesting?

It’s the willingness to believe that Americans in 1938 were so gullible and so credulous as to be panicked by a radio show.

Also interesting is what I call in Getting It Wrongthe “would-be Paul Revere effect.” This was when well-intentioned people possessing little more than an incomplete understanding of TheWar of the Worlds broadcast, set out to warn others of the sudden and terrible threat. These would-be Paul Reveres burst into churches, theaters, taverns, and other public places, shouting that the country was being invaded or bombed, or that the end of the world was near. A false-alarm contagion took hold in a number of places that night, mostly in New York and New Jersey.

The unsuspecting recipients of what were typically jumbled, second- and third-hand accounts had no immediate way of verifying the troubling news they had just received so unexpectedly. Unlike listeners of the radio show, they could not spin a dial to find out whether other networks were reporting an invasion. This second- and third-hand fright didn’t last long. It was evanescent. But it is interesting that the show caused some level of apprehension among many people who had not heard one word of the program

This would-be Paul Revere effect is a little recognized subsidiary phenomenon of the broadcast.

What accounted for the spread of the War of the Worlds myth? Why does the myth persist today?

Newspaper accounts published the day after the radio dramatization laid down what has become the dominant narrative that the show created mass panic and hysteria. This notion was solidified by newspaper editorial commentary published in the days immediately following the broadcast. For newspapers, Welles’ radio spoof offered an irresistible opportunity to rebuke radio as an unreliable, untrustworthy, and immature medium.

The New York Times said, for example: “Radio is new but it has adult responsibilities. It has not mastered itself or the material it uses. It does many things which the newspapers learned long ago not to do, such as mixing its news and advertising.”

And the Chicago Herald-Examiner said: “Radio news is frequently unreliable, and often sensational and alarming. Radio news ought to be presented with the same restraint that is exercised by newspapers….”

The newspaper-radio rivalry certainly was not new in 1938. It had taken shape during the 1920s. But by 1938, radio’s immediacy in bringing news to Americans had become very apparent—and was troubling to newspapers. Radio was becoming the principal medium for reports of breaking news. It was an increasingly important rival medium to newspapers. And newspapers seized the occasion to bash radio in the aftermath of the show. This unrelievedly negative commentary reinforced the notion that TheWar of the Worlds program had sown panic and mass hysteria among Americans.

Are there contemporary claims about media impact that are similar?

Interestingly, a couple of fairly recent cases have evoked the supposed reaction to TheWar of the Worlds program. In March 2010 in the former Soviet republic of Georgia, a privately owned television station broadcast a phony report that Russia was invading the country. The station used to dramatic effect taped footage of Russia’s incursion into Georgia in 2008, passing it off as a new assault. The phony report caused and, reportedly, a brief spasm of confusion and consternation in Georgia.

It was supposed to have political satire of some sort, but it really backfired on the station.

The episode reminded many people of TheWar of the Worlds broadcast.

So did a phony report on state-run television in Belgium in 2006, which told of the sudden abdication of the royal family and the unilateral claim of independence by the Dutch-speaking half of the country. The television network, RTBF, said the program demonstrated the importance of debating the country’s future. But few people agreed; nor were they much amused.

How do you use this case in the courses that you teach in journalism?

I use it eagerly, around Halloween time, in classes in which the subject is relevant. I play a portion of a recording of the program— usually the first 20, 25 minutes—and pass around Halloween candy as the dramatization unfolds.

Supposedly, it was about 20 to 25 minutes into the show when listeners in 1938 began panicking. I lead a discussion among students about what internal clues listeners could have detected to confirm that it was a dramatization and not an alien invasion. Events moved far too quickly, for example. That’s a pretty obvious clue: In less than 30 minutes, the Martians blasted off from their planet, traveled across space to Earth, landed in New Jersey, set up their heat rays, and launched their devastating attack. We also discuss external evidence that listeners could have checked, too. Such as consulting the day’s newspaper listing of scheduled radio programs.

I have taught an honors colloquium three times that draws specifically on the myths debunked in Getting It Wrong. In those classes, I have required students to visit the Library of Congress to research newspaper coverage of The War of the Worlds show. It’s been a very successful assignment in that it introduces students to the resources of the Library of Congress and requires them to scrutinize microfilmed issues of a newspaper published long ago.

In the YouTube clip below, you can watch W. Joseph Campbell discuss the War of the Worlds media myth:

See Also:

W. Joseph Campbell’s blog and web site Media Myth Alert.