S.C. Black Freedmen Organized First Memorial Day Celebration In 1865

My man Ta-Nehisi Coates has proven once again why I always click the link to his blog over at The Atlantic when the minutia of the internet starts trending towards nothingness. Today Coates features some excerpts from a piece by Harvard historian David Blight in the New York Times that describes the first celebration of what we have now come to know as Memorial Day.

I’ve decided to include some different excerpts from the same article here on my own blog at Big Think, mostly because I grew up seventy miles from Charleston, S.C. and I am embarrassed to admit that I have never heard of this before now.

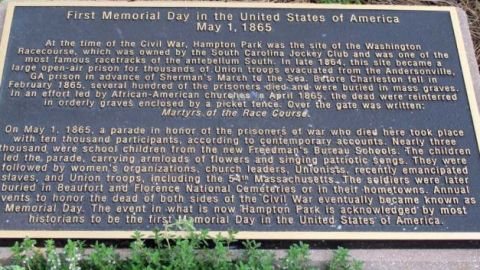

After the Confederate evacuation of Charleston black workmen went to the site, reburied the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

The symbolic power of this Low Country planter aristocracy’s bastion was not lost on the freedpeople, who then, in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged a parade of 10,000 on the track [in May, 1965]. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

The procession was led by 3,000 black schoolchildren carrying armloads of roses and singing the Union marching song “John Brown’s Body.” Several hundred black women followed with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses. Then came black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantrymen. Within the cemetery enclosure a black children’s choir sang “We’ll Rally Around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner” and spirituals before a series of black ministers read from the Bible.

After the dedication the crowd dispersed into the infield and did what many of us do on Memorial Day: enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches and watched soldiers drill. Among the full brigade of Union infantrymen participating were the famous 54th Massachusetts and the 34th and 104th United States Colored Troops, who performed a special double-columned march around the gravesite.

“What’s interesting to me is how the memory of this got lost,” Blight said. “It is, in effect, the first Memorial Day and it was primarily led by former slaves in Charleston.”

While talking about the Decoration Day event on National Public Radio, Blight caught the attention of Judith Hines, a member of the Charleston Horticultural Society. She was amazed to hear a story about her hometown that she did not know. “I grew up in Charleston and I never learned about the Union prison camp,” Hines said. “These former slaves decided the people who died for their emancipation should be honored.”

Thank you, Professor Blight, for your efforts to expand the official narrative of our nation’s history to include all of the instances of Americans who have sacrificed their lives for our freedom. And thank you to the Avery Research Center in Charleston for holding on to the details of our history.