Vision Loss: The Forgotten German Prophets Secretly Behind Modern Art

The forgotten aspects of art history will always be the most intriguing. Digging up the dead storylines of art history, whether in the distant or the recent past, will never end, mostly thanks to forces that buried the facts, if not the bodies, for whatever agenda. Artists and Prophets: A Secret History of Modern Art 1872-1972 at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt resurrects German visionaries and Jesus wannabes from the late 19th and early 20th centuries to look at how their exploits and artistic creations helped shape the course of German and European modern art. It also shines light on how the impact of those figures fell into obscurity as another casualty of the ideological war waged by that most unfortunately unforgettable of German messianic aspirants — Adolf Hitler.

In the German and English exhibition catalog, Curator Dr. Pamela Kort sees the “circumstances,” political and otherwise, of Europe generally and Germany specifically around 1872 “giv[ing] rise to artists-cum-prophets who were not just religious dissenters but social revolutionaries of a kind.” Their influence stretches all the way to the disastrous post-World War I era of 1920s hyperinflation that spawned the “inflationary saints” of the Weimar Republic who offered solace to the suffering population. When Hitler and the National Socialists likewise capitalized on the inflationary hunger for meaning and stability, they eliminated the visionary competition by outlawing occultism in 1937. Unfortunately, for Kort’s “artists-cum-prophets,” after the fall of the Nazis in 1945, the push to erase the charismatic hold of Hitler lumped in these visionaries as well.

As Kort puts it, “Ever since the Enlightenment there had been little place for the irrational in German-speaking Europe. The apocalypse initiated by the ‘false’ prophets of the Third Reich only further sealed the case.” The mystic nature of the artists in Artists and Prophets proved their undoing in the eyes of history, but that same irrational appeal caught on with like-minded and like-spirited modern artists who built upon their ideas and gave them physical form in art.

From vegetarianism to nudism to proto-Dadaism, these visionary artists provided a template for later German artists to follow, usually with little to no acknowledgement of the spiritual source. “At the heart of this book,” Kort asserts, “is the view that, despite their largely having been written out of art history … [such artist-prophets] were not only well known in avant-garde circles but often secretly esteemed by them. There were also more than a few in the cultural world who helped themselves freely to their ideas, without bothering to credit them … It is high time that this secret history of art be told.”

The exhibition centers around five key figures of German spirituality: Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, Gusto Gräser, Gustav Nagel, Friedrich Muck-Lamberty, and Ludwig Christian Haeusser. Barely known within Germany today and entirely unknown beyond it, these figures come back to life in this exhibition and Kort’s catalog essays. “There were many others, but none so well known as these,” Kort writes in defense of her choices. “Each of them possessed a high degree of charisma, and each also felt ‘called upon personally’ to propagate their revelations ‘for their own sake and not for fees.’” Kort masterfully unravels the tangled history of German spiritualism and combs out the faithful from the Thomas Kinkade-like frauds.

Diefenbach, dubbed the “Vegetarian Apostle” due to his promotion of the vegetarian fad that spread across Germany beginning in the 1860s (and even turned Hitler meatless), stands as the spiritual and artistic source of the exhibition’s narrative. In response to the stiff moralism of creeping Victorianism and belligerence of blossoming nationalism of late 19th century Europe, Diefenbach preached nudism and pacifism while trekking across Germany collecting apostles and future visitors to his commune Monte Verità, the “mountain of truth.” His back-to-nature philosophy, which also embraced the mystic theosophy then en vogue, as well as his long-haired, “personal Jesus” personality inspired generations of less-spiritual, less-scrupulous copycats, but also a flock of devoted followers from the faith and art fields.

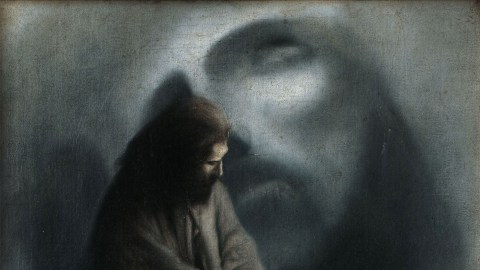

The quality of the art of the visionaries, including that of Diefenbach, strikes modern eyes with a “you had to be there” feeling. Diefenbach’s The Prophet (detail shown above; ca. 1892) may be a self-portrait of Diefenbach himself brooding over his destiny in a kind of “Gethsemane” moment. The Prophet carries all the philosophical weight of the Art Nouveau and Symbolist schools, but sinks under a lack of skill compared to those movements’ best practitioners. As is the case with so many of these artists-prophets, Diefenbach’s more prophet than artist, but you can’t question the appeal of the combined skill sets, however unequal.

It’s when you get to artists who drank the prophetic Kool Aid that Artists and Prophets really proves its emphatic point and makes a valuable connection between these prophets and modern art history. The star of Artists and Prophets is Egon Schiele, who not only steals the spotlight on the exhibition’s front page and catalog cover, but also best embodies Diefenbach’s legacy, from the startling nudes that championed nudism to the mystical symbolic works that dealt with death and its spiritual implications. Schiele’s personal artistic spirit guide, Gustav Klimt, doesn’t appear in the show, but Kort makes clear the connection between Klimt and these spiritualists generally and the (unacknowledged) link between Klimt’s 1902 Beethoven Frieze and Diefenbach’s 1892 Per aspera ad astra frieze that Klimt undoubtedly saw and took tips from.

Artists and Prophets builds its case beautifully with selections from other prophet-inspired artists such as František Kupka, Johannes Baader, and Heinrich Vogeler, but the two key modern German artists embodying the post-World War II influence are Joseph Beuys and Friedensreich Hundertwasser. Hundertwasser’s ecstatically colorful canvases capture the vividly alive nature of the earlier visionaries, while Beuys adoption of the performative aspects of those same prophets set the stage for modern performance art itself. Beuys styled himself as a kind of messianic figure of modern art and, as Kort proves, clearly knew the story of Diefenbach, but in the post-war climate hostile to pre-war messiahs thanks to Hitler’s charismatic chaos, Beuys allowed himself to be seen as an original, sprung wholly created from his own head with no allegiances to the troublesome German past except for those he could control and convert into his art.

As Jesus himself reportedly said, “A prophet is not without honor, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house.” Artists and Prophets: A Secret History of Modern Art 1872-1972 honors the memory and legacy of forgotten artist-prophets such as Diefenbach and rewrites a lost chapter in the history of modern art. It’s hard to pinpoint the beginning of any art movement as untidy as that of performance art, but it’s nearly impossible to avoid the influence of Joseph Beuys. So, if you can link Beuys to a forgotten predecessor, you’ve accomplished a great deal in illuminating the roots of performance art, which may be the most significant art medium today. Just as the upcoming film Woman in Gold brings the issue of restoring Nazi-stolen art to its rightful owners to the masses, Artists and Prophets restores a Nazi-stolen legacy to its rightful owners, both the forgotten names and we who have forgotten.

[Image:Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach. The Prophet (detail), ca. 1892. Oil on canvas, 56,5 x 44,5 cm (63 x 51 cm). Sammlung Schmutz, Wien. © Marta Gómez Martínez.]

[Many thanks to the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt for providing me with the image above from, a review copy of the catalog to, and other press materials related to Artists and Prophets: A Secret History of Modern Art 1872-1972, which runs through June 14, 2015.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]