“Starf@#king”?: Björk at the MoMA

It’s hard to remember a major show at a major American museum generating so much angst as Björk at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Some arts sites quickly began aggregating art critics’ aggravation over almost every detail of the show. What began as art criticism evolved into a media lynching of the MoMA, American museums, and pandering-to-the-public curators (in this case, Klaus Biesenbach). New York art world critics, and husband-and-wife team, Jerry Saltz and Roberta Smith hated the show in different ways, but both connected to their love of Björk and her music. ArtNews’ M.H. Miller wins the poison pen prize, however, for coining the new critical term “starf@#king” to describe the MoMA’s treatment of Björk as much as its treatment of the viewing public. The question of whether Björkis good or not might really be a question of what Björk is really about.

Saltz saw it coming, citing an earlier piece on the show as evidence. Listing other pop star-focused museum shows, Saltz writes that, “By now all of these shows feel like the museum trying to boost its numbers, pandering, and at sea.” Another “red flag” for Saltz was the curator, Biesenbach: “I reasoned that his fan heart was sure to get in the way of this being done in an erudite, historically contextualizing way, placing the art and the artist in her own time.” Finally, even though Saltz claims to admire Björk, he “whined about MoMA being unable to think of any other living or dead artist for such a show.” At least Saltz is honest enough to admit his prejudices, even if he congratulates himself on all of them coming true, at least in his view. Smith shows more unequivocal admiration for Björk and damns the MoMA for lacking “the ambition to do her ambition justice.” For Smith, the exhibition failed to do Björk justice.

Miller minces few words in his hatred not just of the show, but also of the previewing experience itself. Comparing the Björk exhibition experience to Planet Hollywood and the Hard Rock Café, Miller declares a “state of emergency” for the MoMA in the title of his piece. Miller lands his coup de grâce on the show and similar exhibitions with his final words: “And the show is hardly a retrospective — it’s starf@#king, something increasingly familiar at MoMA, and a failure even at that.” In both conception and execution, the critics seemingly all agree that Björk is a mess, and a not very hot one.

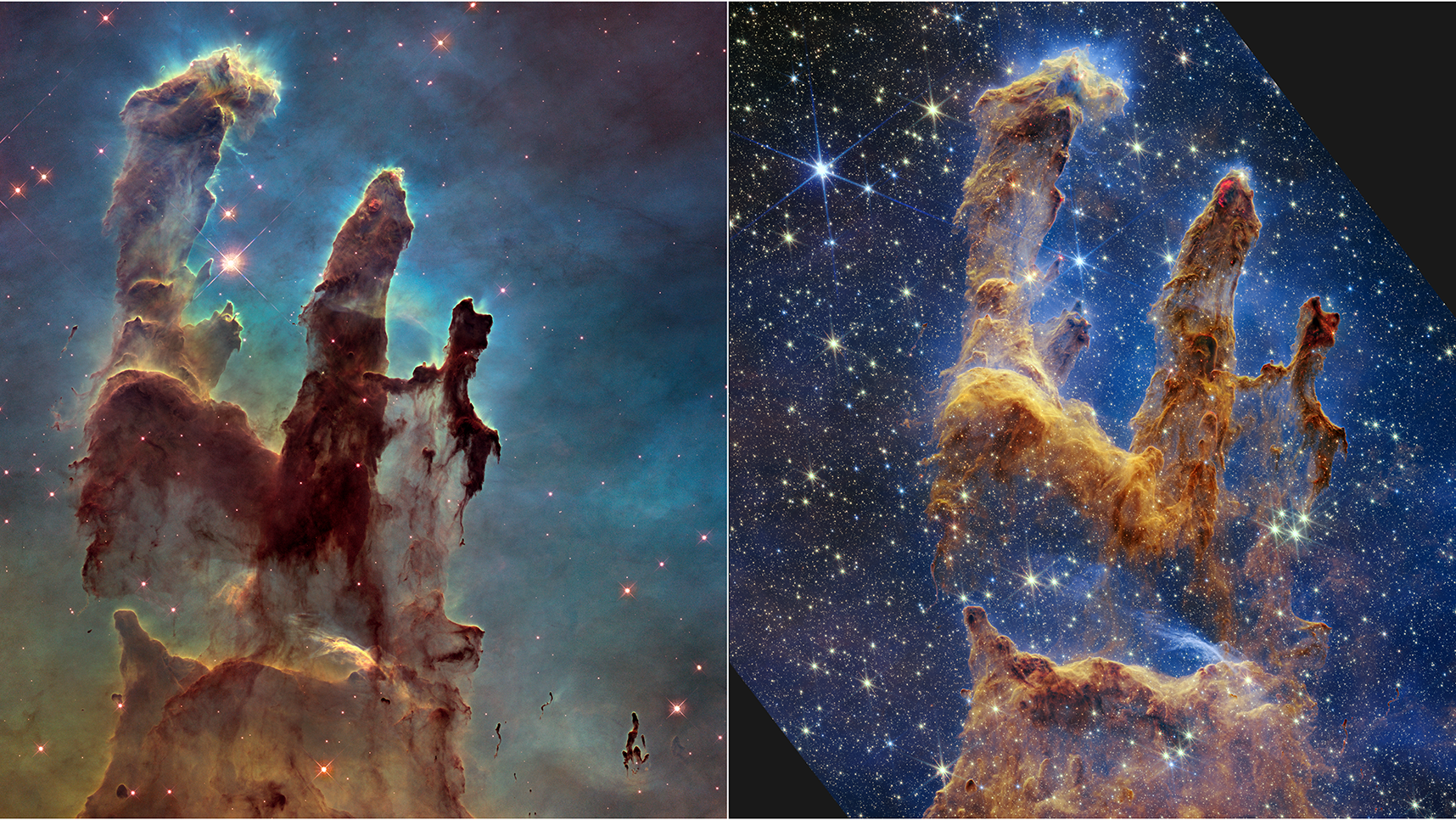

What were the MoMA’s intentions? According to the press release, it hoped for “a retrospective dedicated to the multifaceted work of the singer, composer, and musician” that “offers an experience of music in many layers, with instruments, a theatrical presentation, an immersive sound experience, a focused audio guide, and related visualizations — from photography and music videos to new media works.” Biesenbach imagined packaging “a chronology of sounds, videos, objects, instruments, costumes, and images that express the artist’s overarching project: her music.” In other words, you’ll come for the “swan dress,” but stay for the music, including “Black Lake” (still shown above), a new, 10-minute music video from her new albumVulnicura, directed by Andrew Thomas Huang, and especially commissioned by the MoMA for the exhibition.

How did those intentions play out in the minds of the critics? The promised innovations turned out to be disappointingly minor modifications on now-standard museum audio guides and presentations. The Icelandic poet Sjón’s fairy-tale approach to Björk’s life story annoyed more than charmed the critics listening to it as they wandered through the exhibition. Apparently quite legitimate logistical concerns involving foot traffic through the video spaces only further frayed critics’ nerves. What the MoMA dreamt of as playful and fun played out at the preview as trite, clichéd, and infantile.

Was that a fair assessment? I didn’t attend the Björk preview, but I can personally attest to the touchiness of some press members at such events. For me, the key to the puzzle of this disconnect between museum and media hid in music critic Alex Ross’ catalogue essay, “Beyond Delta: The Many Streams of Björk” (excerpted here). Ross takes his title from avant-garde composer John Cage, who said, “We live in a time I think not of mainstream, but of many streams, or even, if you insist, upon a river of time, that we have come to delta, maybe even beyond delta to an ocean which is going back to the skies.” In that quote, Cage claimed that the increasing fracturing of music into genres and subgenres might be reaching a turning point, a place where the musical mainstream and other musical minor streams converge as a “delta” feeding an “ocean” where such labels lose meaning. Ross goes on to see “[i]n the intersecting tributaries of Björk’s work … a glimpse of the delta that Cage described at the end of his life — whether or not Cage himself would have been able to wrap his mind around her music.” Björk thus becomes the great, unifying hope for a global musical future (and all the cultural, social, etc., unifications that would follow).

Ross ends with the idea that, “[a]s in Franz Schubert’s final string quartet or Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite, [Björk’s] music has a seismographic action, recording shocks and sensations that we may not see firsthand.” Is Björk the exhibition, like Björk’s music, such a secretly cataclysmic, earth-shaking show that even the critics can’t feel its effects? How long will it take us to catch up with the aftershock, assuming there actually is one? If the critics can’t catch up, what hope does the public have? Ultimately, is this a show in search of an audience that does not yet exist? Or, even worse, if you side with the critics, is this a show made with no consideration for the audience at all?

The Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott made what remains, for me, the most interesting critical point about the show. “Of all the visual delights and exotica on display at the Museum of Modern Art’s Björk exhibition — androgynous robot sex, canoodling with snakes in the rain forest, and the famous Alexander McQueen ‘Pagan Poetry’ dress with its drafty upper reaches — perhaps the most quietly shocking was the visual presence of actual music,” Kennicott writes. “Yes, printed music, pasted on the walls where visitors queue to enter the multimedia ‘Songlines’ galleries, and also on the covers of the multiple catalog inserts.” After noting that printed music’s “all been banished” from mainstream classical music books or even concert programs, Kennicott concludes that “[t]he visual presence of music — except rarely as a fuzzy decorative background over which something else has been printed — is seen as off-putting, even terrifying to newcomers.”

The lack of music played in the home and, hence, musical literacy leads to these fears, of course, but there’s also a sense of class conflict in which notated music serves as a stand in for classical music and, by unfair association, elitism. But if people could overcome those fears, perhaps through the accessibility and playful fun of Björk’s multi-genre, multi-persona approach, perhaps we could truly get “beyond delta” as Cage (and Ross) propose. I recall how the presence of musical notation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 2012 exhibition Dancing Around the Bride helped make imposingly difficult artists such as Cage and Marcel Duchamp “friendlier.” Here was music as a language that could be written down, such displays say, and what can be written down can be shared and understood, given enough effort to crack the code.

Björk may remain a hard code to crack, not only for the critics, but also for the interested, but annoyed viewing public stuck in long lines and listening to off-putting audio. But I think the major problem with the show is that the smallest, quietest elements — the notated music, and what it means — can’t compete with the bigger, louder elements of costumes and videos. You’ll come for the “swan dress,” stay for the music, but you should leave with a new appreciation of how music (and art) unites rather than divides us, given the proper appreciation of it as a human language designed to communicate rather than confound. Is Björk merely “starf@#king”? If we see it as just that — no matter how poorly conceived or executed — maybe we are truly screwed.

[Image:Björk. Still from “Black Lake,” commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and directed by Andrew Thomas Huang, 2015. Courtesy of Wellhart and One Little Indian.]

[Many thanks to The Museum of Modern Art, New York, for providing me with the image above from, a copy of the catalogue to, and other press materials related to the exhibition Björk, which runs through June 7, 2015.]