Repairing the World: The Road to The Rothko Chapel

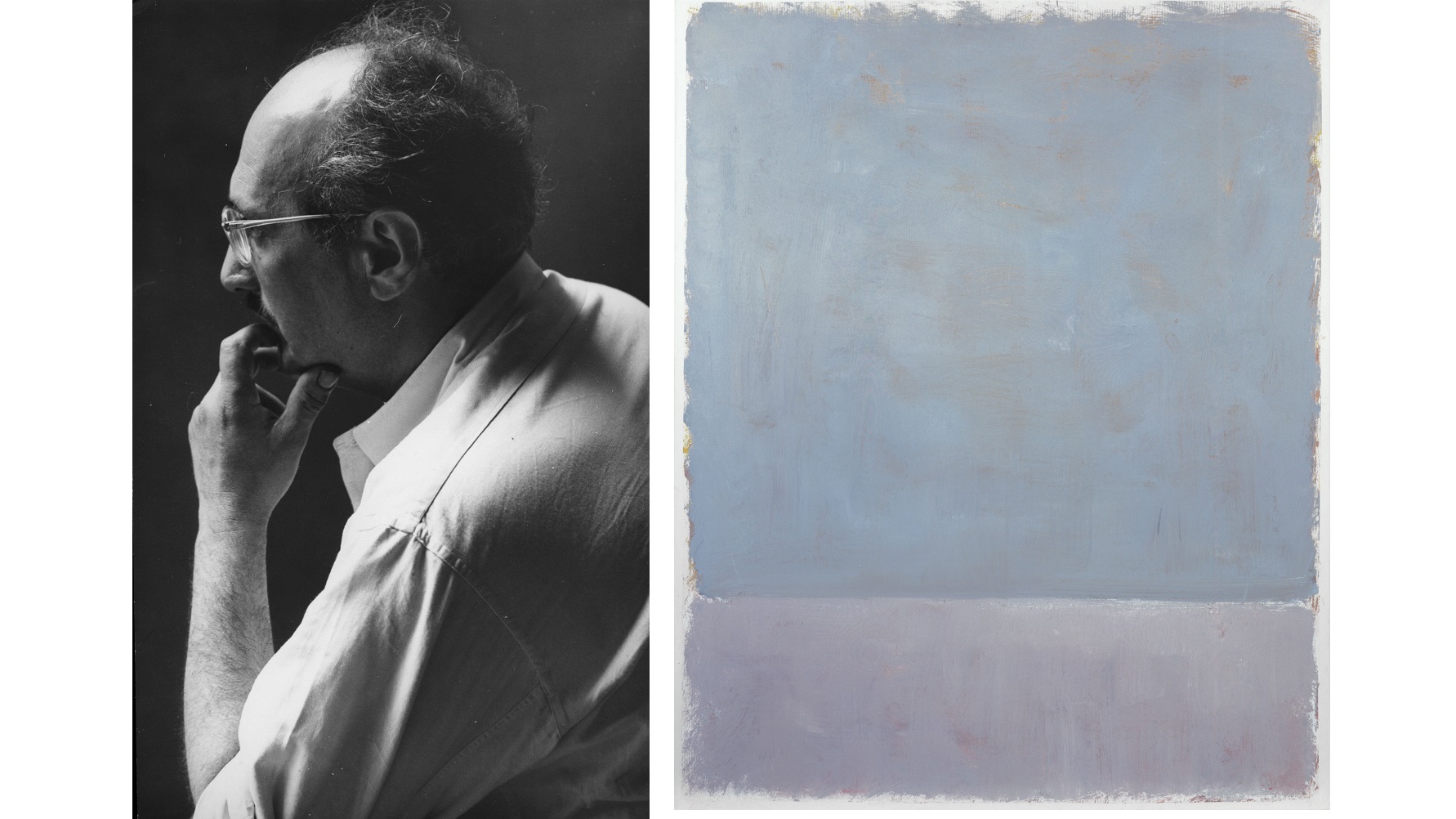

Of the many concepts of Judaism artist Mark Rothko took to heart, the idea of tikkun olam, Hebrew for “repairing the world,” penetrated the deepest. In Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, academic and a cultural historian Annie Cohen-Solal cuts to the heart of Rothko’s life and art and sheds new light on how both seemingly had to end at The Rothko Chapel (shown above), the Houston home of Rothko’s final works that he tragically didn’t live long enough to see himself. In this tightly focused new biography, Cohen-Solal shows us both how The Rothko Chapel culminates Rothko’s life-long mission to repair his world and how it continues to serve as a light of hope in our darkening world.

Born in 1903 in Dvinsk, which is part of Latvia today but then part of the Russian Empire, young Marcus Rothkowitz grew up in a “reading family” and early on studied the Talmud. “This complex relationship to the Talmud,” Cohen-Solal writes, “is in fact a key to understanding the life and work of Mark Rothko.” Cohen-Solal quotes Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s idea that, because the physical Temple in Jerusalem was never rebuilt, “study, the Talmud, has become the real temple of Israel.” Thus, the Talmud becomes the first “temple” or “chapel” in a series of sanctuaries for Rothko.

Throughout Cohen-Solal’s biography, Rothko’s life stands in as a microcosm of the larger 20th century Jewish experience from this “temple” rebuilding to the modern diaspora itself. In addition to color plates of Rothko’s art and black-and-white archival photos from Rothko’s life, Cohen-Solal includes maps tracing Rothko’s emigration to the United States, his transatlantic travels in his final decades, as well as his many studios and homes in New York City spread across four decades. At first, these maps full of arrows and dots seemed more like the study of a migratory bird than that of an artist, but they strikingly convey in pictures what Irving Howe (whom the author quotes) described in words as “a journey of dispersion” taken in the 1950s, when “to become an avant-garde painter meant to become an avant-garde Jew.” Rather than the legendary “Wandering Jew” expiating some blood libel, Rothko and his fellow avant-gardists wander in search of a place of refuge physically, spiritually, and artistically.

Cohen-Solal masterfully places Rothko within the larger contexts of 20th century America society, politics, and art. From traveling cross-country from Ellis Island to Portland, Oregon, with a sign saying he knew no English around his neck, to dropping out of WASP-infested Yale because of the anti-Semitic climate, to finally discovering a world of fellow outcasts in Abstract Expressionist circles, Rothko’s road to acceptance was a long, hard one, but continually one driven by a fierce faith in democratic principles and the communicative power of art working together. “Art is not only a form of action, it is a form of social action,” Rothko wrote, a quote Cohen-Solal wields as the epigram for a chapter titled “In Search of a New Golden Age: 1940-1944.” As the Holocaust raged in war-torn Europe, the nadir of 20th century Jewish life, Rothko never stopped looking for a new golden age in a world of seeming dross.

Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel most likely won’t supplant James E.B. Breslin’s longer Mark Rothko: A Biography as “the” authoritative Rothko biography, but that was never its purpose. From the very title on, you know how the “plot” of Cohen-Solal’s biography ends — at The Rothko Chapel. She reveals and even revels in her naked teleology in comparing Rothko’s own purpose-driven vision of art history with Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s purpose-driven philosophy. Sometimes the “chapels” Cohen-Solal strews throughout Rothko’s life seem like biographical cherry-picking to make an over-arching point that inescapably ends with those 14 black paintings in Houston, but I’ll defend her approach in the name of greater understanding. No single thread of a life, just like no single painting, song, or moment, truthfully encapsulates the more messy existence of any individual, but when you try to wrap your arms around an artistic vision as cosmic as that of Rothko, pulling that one thread from the tapestry may be the best, perhaps only way of embracing it. Breslin’s book may be bigger, but in the sense of deeper understanding, Cohen-Solal’s book is better.

After seeing the paintings at The Rothko Chapel, musician Peter Gabriel wrote the song “Fourteen Black Paintings”:

From the pain come the dream

From the dream come the vision

From the vision come the people

From the people come the power

From this power come the change

Just as Gabriel’s lines build upon one another, Rothko’s road to his finally realized chapel built upon every experience that preceded it. Cohen-Solal’s Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel shows how The Rothko Chapel’s current mission of providing a non-denominational place of peace finally achieved Rothko’s dream of “repairing the world,” if only by changing one little corner of it. At a time when Rothko’s work is selling higher than ever, Cohen-Solal’s book hopefully sells Rothko’s legacy as not just artistic or financial treasure, but rather as call for a healing harmony as timelessly old as “The People of the Book” and as presently urgent as today’s headlines.

[Image:Rothko Chapel, Houston, 2012 by Another Believer – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]