Picturing the Price of Being an Artist

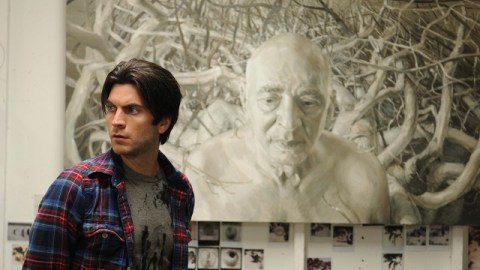

“Artists don’t have families,” the mysterious Warner Dax tells confused painter Daniel at their first meeting in the new film The Time Being. Dax (played by film and theater legend Frank Langella) challenges Daniel (played by Wes Bentley) not just to complete a series of obscure tasks for the cash to keep his struggling career, marriage, and family alive, but also to consider the price he’s paying in the pursuit of art. Time spent painting means time not spent with family. An enigmatic film full of subtle acting and shot in a subtle, but powerfully evocative style, The Time Being thoughtfully examines the cost of the creative life and seriously asks if it is truly worth paying.

We first encounter Daniel as the stereotypical struggling artist lovingly supported by loving wife and son but straining under the weight of conflicting responsibilities. All seems straight out of central casting as we witness poor sales at a gallery opening complete with the requisite bare red brick walls and the wine-filled clear plastic cups, until a mysterious request reaches Daniel through his dealer. Sniffing a possible commission, Daniel drives to the mystery caller to personally deliver the purchased paintings and show his latest work. Bentley, who played Seneca Crane in The Hunger Games, subtly but clearly portrays the hunger of a young artist for both critical and commercial recognition.

Daniel’s trek to Dax’s tastefully decorated home reminded me of naïve, yet ambitious Jonathan Harker’s trip to Count Dracula‘s castle, probably because I knew one of the great stage and film Draculas—Frank Langella—waited at the end of the hallway. Langella’s played every type of bloodsucker from vampires to politicians and Dax joins that list, but with an especially frosty ruthlessness that’s downright Nixonian. Daniel’s clearly overmatched by Warner in the negotiations, but as the story unfolds, we find that the two men have much more in common than Daniel’s suspects.

Warner offers Daniel payment for filming different scenes to his exact specifications. A request for a specifically staged sunset seems eccentric but acceptable. A second job to film children on a playground skirts the edges of pedophilia, but Daniel hesitatingly accepts. A third request to film a museum exhibition tour sets in motion the events that both reveal Warner’s real intentions as well as delve even deeper into the issue of being an artist and a member of a family at the same time.

Nenad Cicin-Sain, director and co-screenwriter (with Richard N. Gladstein) of The Time Being, envisioned his directorial debut as not just telling us about Daniel’s evolution catalyzed by Warner, but showing us as well through the cinematography. Daniel begins as a painter of black and white still lifes of decomposing fruit (painted in real life by artist Eric Zener). Daniel’s paintings reflect his black-and-white view of the world, as well as the deterioration of what once held so much promise in his art and life. As Daniel conceptualizes his life in a new way, he turns to conceptual art that includes the human figure as well as all the colors of life (painted in real life by artist Stephen Wright). “[T]here is no red in the film in the first half and no blue until three quarters of the way in,” Cicin-Sain explains. “Emotional events trigger colors, music and tone. In most films a protagonist goes through some kind of change. I feel a film should do the same.” Cicin-Sain cites Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography on Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1970 film The Conformist as an influence, and you can see the same simplicity and nuance of visual storytelling.

As much as Daniel wants to conform to his own idea of a great artist, a part of him continually wants to step back from the brink and return to the safe haven of his family. The Time Being asks in a very simple, but moving way how and why anyone, not just artists, spends their time being. The question of whether you can you ever have it all actually boils down to can you ever have the time to have it all. While Daniel films time’s fluid movement of the rising sun against the seascape, his wife and son play on a beach—literally offering him a grounding place to save himself from drowning in his own ambition. At times, The Time Being might actually be too subtle for many to catch Cicin-Sain’s drift, but if you slow down enough and give into the visual and narrative flow, The Time Being is time well spent.

[Image:Wes Bentley as Daniel beside a portrait of Frank Langella as Warner Dax in The Time Being, distributed by Tribeca Film. Portrait by Stephen Wright.]

[Many thanks to Tribeca Film for providing me with the image above from, press materials for, and a screener copy of The Time Being, starring Frank Langella and Wes Bentley and opening in select theaters on July 26, 2013.]