Omnivore’s Dilemma: Rethinking John Singer Sargent

The standard line against painter John Singer Sargent goes like this: a very good painter of incredible technique, but little substance who flattered the rich and famous with decadently beautiful portraiture — a Victorian Andrea del Sarto of sorts whose reach rarely exceeded his considerable artistic grasp. A new exhibition of Sargent’s work and the accompanying catalogues argue that he was much more than a painter of pretty faces. Instead, the exhibition Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends and catalogues challenge us to see Sargent’s omnivorous mind, which swallowed up nascent modernist movements not just in painting, but also in literature, music, and theater. Sargent the omnivore’s dilemma thus lies in being too many things at once and tasking us to multitask with him.

Sargent scholar Richard Ormond succinctly explains in the catalogue how this show differs from previous ones: “What materialises here is a painter in the vanguard of contemporary movements in the arts, in music, in literature, and the theatre. His enthusiasms were for all things new and exciting; he was a fearless advocate of the work of younger artists, and in music, his influence on behalf of modern composers and musicians ranged far and wide. … Sargent the painter is well-known; but Sargent the intellectual, the connoisseur of music, the literary polymath is something new.” Sargent’s closest friends were artists because he most easily befriended fellow artists who energized his own artistic vision. The portraits in Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends not only document his circle of trusted friends, but also display the worldwide web of associations that made Sargent an artist.

Sargent the modernist seems an odd phrase for someone so associated with the Gilded Age, but it’s not gilding the lily to say that Sargent shares many modernist traits. It’s true that the world was much bigger and less well-connected than technology allows today, but Sargent was truly an international man of mystery. Born to expatriate American parents in Florence, Italy, Sargent traveled Europe throughout his childhood and youth, picking up languages and cultures like souvenirs. In a smaller, more user-friendly catalog to the show, Barbara Dayer Gallati describes the great melting pot of Sargent’s mind as “the hybrid nature of his cultural identity.” Sargent isn’t the man without a country as much as the man of all countries. For Sargent, it was a small world after all, with all the cultures of the Western world (and many outside it) easily within his reach thanks to the connections he made throughout his life. For Gallati, “additional insight into the mind of Sargent may be gained by considering the labyrinthine, international matrix of artists, musicians (he was a talented pianist himself), writers, actors, and patrons who were his friends and muses.”

The most apt contemporary analogy for viewing the portraits in Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends is scrolling through someone’s Facebook friends to learn about them. Looking at each portrait opens a door into an artist of the past (many forgotten today) that also reveals a dimension of Sargent. Unless you’re already an authority on the arts of the period, reading more deeply into the background of each portrait is essential, thus making the catalogue essential reading. (The smaller, more portable catalog makes up in convenience and insightful brevity what it sacrifices in depth as a gateway into understanding the significance of each portrait.)

The Met organizes the exhibition chronologically as it follows Sargent’s travels from Paris (where he finished his formal art training), to London (where fellow expatriate American Henry James introduced him to wider arts circles), to the Broadway artists’ colony in the English countryside (where he let his inner Impressionist finally roam free), to America (especially the high society of Boston and New York), to Italy, and to the Alps. The common thread in all these adventures is Sargent’s omnivorously inquisitive mind, which, as Ormond neatly describes, was “open enough to seek, smart enough to grasp, and gifted enough to use all that he found.”

It’s ironic that we see Sargent as an arch conservative today, while his contemporaries saw him once as the arch radical. The Met’s own Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau) stands in the middle of the exhibition to testify how Sargent once found himself ostracized by the social set he hoped to gain commissions from as a portraitist. Sexy Madame X with her (once) daringly dangling shoulder strap (later painted into a respectable place) marked Sargent as a dangerous painter. However, as Ormond points out, “It took less than a decade in England for Sargent to pass from arch-apostle of the ‘dab and spot’ school [of Impressionism] to establishment portrait painter.” Yet, even when he joined the establishment, Sargent found ways to work his daring, modernist ideas into portraits that would please patrons looking for immortality but also philosophically open to his aesthetic.

Those most philosophically open to that aesthetic were, of course, fellow artists. Sargent’s two portraits of author Robert Louis Stevenson seem today like candid celebrity snapshots from People magazine in their daring informality: one in which Stevenson walks and talks across the image alive with ideas and a second showing him in repose, face still alive with ideas, but a smoldering cigarette indicating his comfort with the painter. Around the same time Sargent painted one of his most signature works, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. Featuring the children of fellow artists lighting paper lanterns at twilight amidst the titular flowers, “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose is poised between several aesthetics: French Impressionism, English Pre-Raphaelitism, and Aestheticism,” Elizabeth Kornhauser writes. Sargent’s amazing synthesizing mind created an image of beauty and daring that’s lost its bite today because we’ve grown more comfortable with art movements that once challenged the status quo.

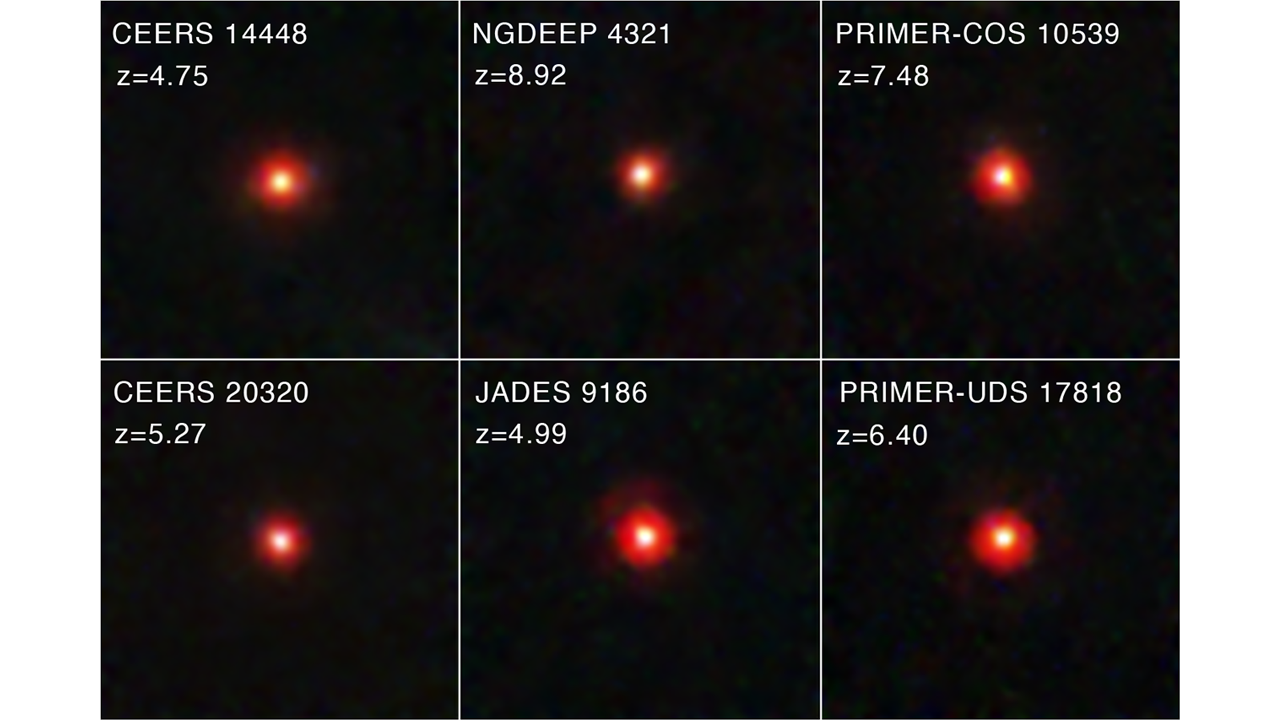

That paradox of comfort and challenge emerges most strikingly in the work Group with Parasols (Siesta) (shown above). Although the 1904 work shows four of Sargent’s friends (including fellow artist Peter Harrison) sleeping in an Alpine meadow, “[t]heir identities, however, [are] irrelevant to the pictorial agenda, which was to evoke voluptuous mood through painterly pyrotechnics,” Trevor Fairbrother explains. Ormond sees Group with Parasols displaying Sargent’s “modernist credentials in the way that he crops and foreshortens the composition and flattens the space.” At the same time Picasso earns his modernist “street cred” by flattening the picture plane, Sargent’s doing the same thing, all while composing an image that up close is a jumble of color and brushstrokes (a “coruscating frenzy,” Ormond calls it) that only resolves into a jumble of human figures when you pull away. To fall asleep on Sargent’s modernism is to miss such electric moments. In Group with Parasols, Sargent’s almost daring us to nap on him.

Aside from these masterpiece moments, Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends shows us what it was like to be an artist at the time. Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood allows us to peek at the Impressionist in action, out in the open air, all done in the Impressionist style he helped shape. An Out-of-Doors Study captures Sargent’s long-time friend Paul Helleu at work in the field while giving a sense of the energy of the moment through the vigorous brush strokes that bring even the grass vibrantly alive. I didn’t know Dennis Miller Bunker before Sargent’s portrait of him painting at Calcot, which shows the younger artist stepping away from his canvas in a moment of thought (or doubt), but now I want to know more about this early American Impressionist who died at 29. Sargent’s affectionate portrait of the troubled Italian genius Antonio Mancini, whom Sargent called “the best living painter,” typifies the love and respect Sargent had for his craft as well as for those who would suffer for it.

“Such men wake one up,” artist Julian Alden Weir wrote of Sargent upon meeting him as a fellow student entering the competitive art world. Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends will awaken you to the depths behind the beautiful surfaces of Sargent’s portraits and challenge you to engage with the arts on a similar scale. I found myself Googling the names of the artists and musicians Sargent knew and loved, but that were unfamiliar to me. While listening to the music of Sargent’s friend Emmanuel Chabrier, I wondered what Sargent would do with today’s technology. Would his worldwide web of artistic associations be even wider? Would we be playing “Six Degrees of John Sargent” instead? If nothing else, Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends reminds us (to steal Ormond’s words) to be open enough to seek while hoping (the omnivore’s dilemma) to be smart enough to grasp, and gifted enough to use all we find.

[Image:John Singer Sargent (American, Florence 1856-1925 London). Group with Parasols (Siesta), 1904. Oil on canvas, 22 3/8 × 28 9/16 in. (56.8 × 72.5 cm). The Middleton Family Collection.]

[Many thanks to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, which runs through October 4, 2015. Many thanks also to Rizzoli USA for providing me with review copies of John Singer Sargent: Painting Friends by Barbara Dayer Gallati and Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends written by Richard Ormond, text by Elaine Kilmurray, with contributions by Trevor Fairbrother, Barbara Dayer Gallati, and Erica Hirshler.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]