JFK: The Opera?

Whereas European countries were once able to tap into their history for subjects for opera, America’s never succeeded in doing the same. That problem comes in part from the decline in opera as a popular, public art form, but also perhaps from the lack of operatically epic subjects to be found in American history. Now, composer David T. Little hopes to create a modern American opera with JFK, a 2-act, 2-hour opera focusing on the life of President John F. Kennedy, whose life and death became defining moments not only for the Baby Boom generation, but also, many would suggest, the hinge upon which all American history turns for the last half century. Set to premier in 2016, JFK as a work-in-progress already raises important questions about how opera (and art in general) can approach history.

When I first heard that there was going to be an opera titled JFK, I thought Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK had somehow been set to music. Imagine a Kevin Costner-esque baritone pleading with a jury for justice for the “dying king” as New Orleans DA Jim Garrison while a Joe Pesci look-a-like sings falsetto counterpoint about “a mystery wrapped in a riddle inside an enigma” as a ghostly David Ferrie. Staging Stone’s intriguing, if muddled work would be worth it not just to see a brooding Lee Harvey Oswald tread the boards, but to make dramatic sense of the most convoluted, character-overfilled plot this side of Wagner’s Ring.

But Little’s JFK focuses not on the posthumous life of its subject but on that final day before the motorcade in Dallas. If John F. Kennedy is the mythic, Christ-like, sacrificial lamb of the modern American narrative, Stone’s JFK is the mad, post-Resurrection scramble to write the gospels, but Little’s JFK is Kennedy’s Gethsemane, with Fort Worth standing in for the Mount of Olives. Instead of focusing on the events of November 23rd, 1963, Little and librettist Royce Vavrek turn back the clock to November 22nd, which the President and his wife spent in Fort Worth as part of their tour through Texas on the way to Dallas. (The Fort Worth Opera and American Lyric Theatre commissioned the work, which will also premier in Fort Worth in 2016.)

Little said in an interview that he hopes to examine “the joys and anxieties” of Kennedy at that moment through flashbacks and dream sequences in which the past and possible futures come alive on the stage. As Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis’s book, Dallas 1963 masterfully laid out, Dallas, Texas, was a difficult, dangerous place for the Democratic president campaigning for reelection in 1964, but one that he needed to court in order to keep his office as well as keep the country together during the tough times of the Cold War. It will be interesting to see how JFK manages to balance the joys and anxieties of such a difficult period for the subject politically and personally.

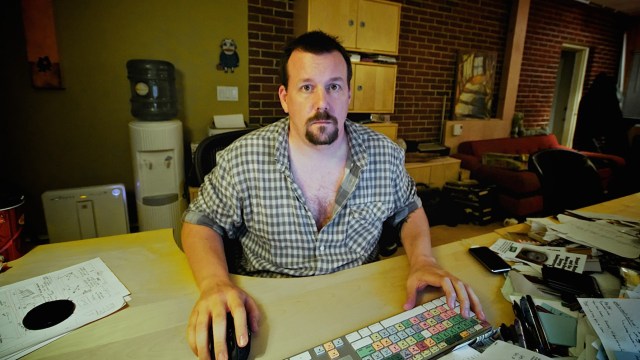

Aside from the content of JFK, the sound of Kennedy’s voice presents a unique problem. Each president carries along his own distinctive, usually heavily parodied verbal tics, but Kennedy’s Boston accent in all its “vigah” belongs in a category of its own. I remember playing my parents’ old Vaughn Meader 1962 comedy albumThe First Family after they had let it languish unheard for decades. Meader parodied the Kennedy accent and the Kennedy clan’s eccentricities to fame, until his career died of bad taste after the assassination. Two hours of Kennedy accented arias could descend into Meader territory, something that Little avoided altogether for a more mainstream voice with baritone Matthew Worth (who certainly looks the part) in the title role. Mezzo-soprano Daniela Mack will play Jacqueline Kennedy, baritone Daniel Okulitch will play Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, soprano Talise Trevigne will play hotel maid Clara Harris, and tenor Sean Panikkar will play a secret service agent and confidant of the President’s.

JFK is only in its earliest stages as workshops (and blogs of those workshops), but Little’s an interesting, thoughtful enough composer to believe that JFK will respect not just the subject, but also the audience and its intelligence. Hagiography in operatic form won’t cut it with modern American audiences already highly allergic to opera. Little, however, has a history of putting history in interesting contexts musically. Little’s Newspeak borrows its title from George Orwell’s 1984 to “explore the grey area where art and politics mix.” In Soldier Songs, Little “explore[s] the perceptions versus the realities of the Soldier, the exploration of loss and exploitation of innocence, and the difficulty of expressing the truth of war.” Perhaps most mind-bendingly, Little’s Dog Days, based on a short story by Judy Budnitz, comically asks from a post-apocalyptic future: “Where exactly is the line between animal and human? At what point must we give in to our animal instincts merely to survive?” (Clips from Little’s previous works can be found here.) Here’s hoping that Little takes the same mindful, nuanced approach to JFK rather than the two-dimensional political caricature that does nobody any good in the search for meaning from the past or for the present.

If Little’s JFK is really Jack on the Mount of Olives, Little might want to take some guidance from the example of Ludwig van Beethoven’s 1802 oratorio, Christ on the Mount of Olives. Not a full-scale opera, Beethoven’s oratorio presents a more human version of Jesus at that moment of crisis, an artistic choice perhaps influenced by Beethoven’s own troubled state of mind as reflected in the Heiligenstadt Testament he wrote around the same time (but wasn’t discovered until after his death in 1827). (You can hear a nice version of Beethoven’s work here.) Whereas others, most famously Beethoven’s personal hero Bach, elevated Christ’s lonely moment before the drama of the Passion to divine levels, Beethoven kept things rooted in the human and Earthly. If Little can bring JFK to realization as the story of a fragile human being on a grand political stage for the opera stage, then it will be a miracle of modern American culture that might just make opera popular and relevant, perhaps for the first time in America.

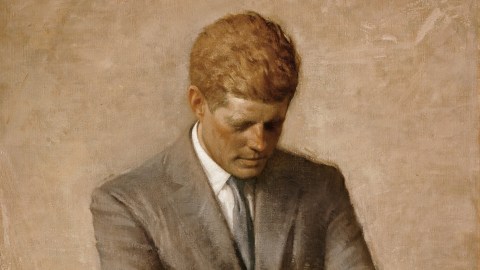

[Image:The Official White House Portrait of John F. Kennedy (detail), by Aaron Shikler. Source: Wikipedia Commons.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]