How Man Ray Made Art of Math and Shakespeare

While advanced math and Shakespeare combine to make a nightmare curriculum for some students, for artist Man Ray, one of the most intriguing minds of 20th century art, they were “such stuff as dreams are made on,” or at least art could be made from. A new exhibition at The Phillips Collection reunites the objects and photographs with the suite of paintings they inspired Man Ray to create and title Shakespearean Equations. Man Ray—Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare traces the artist’s travels between disciplines, between war-torn continents, and between media that became not only a journey from arithmetic to the Bard, but also a journey of artistic self-discovery.

Man Ray’s long, strange trip begins in Paris in 1934. Art historian Christian Zervos commissions him to photograph a collection of three-dimensional mathematical models at the Institut Henri Poincaré. Originally made to serve as algebraic and geometric teaching tools, the models immediately strike the Surrealist photographer with greater artistic potential. Zevros publishes the photographs in 1936 in an issue of Cahiers d’Art centered on the “Crisis of the Object.” That same year, Man Ray’s original photographs appear in several Surrealist exhibitions.

Yet, in 1937, just one year later, Man Ray renounces photography as his main medium in the manifesto titled La Photographie n’est pas l’Art, L’Art n’est pas de la Photographie, literally announcing that photography is not art, and vice versa. After philosophically leaving photography behind him, Man Ray physically left his photographs and other artworks behind as he fled France at the start of World War II for America. By late 1940, Man Ray settled in the then (and now) Surrealist place on earth—Hollywood. “There was more Surrealism rampant in Hollywood,” Man Ray joked later, “than all the Surrealists could invent in a lifetime.” As Andrew Strauss writes in the catalog to the exhibition, Man Ray “reinvented” himself in Hollywood, not only marrying a young dancer but also wedding himself to the idea of working in different media in new and exciting combination.

In 1947, Man Ray returned to France to retrieve his pre-war oeuvre, including his mathematical photographs. Back in America, Man Ray reevaluated the potential of those decade-old pictures. Fellow Surrealist André Breton suggested titles such as “Pursued by her Hoop,” “The Rose Penitents,” and “The Abandoned Novel” back when the mathematical photographs were first taken, but Man Ray went in a different direction when titling the paintings inspired by those photos. “While such poetic titles echoed the playful Surrealist spirit of the mid-thirties,” Strauss writes, “Man Ray felt that refreshing new titles in English could add to their potential popularity and commercial appeal in his new environment.” Man Ray then hit on the idea of using the titles of Shakespeare’s plays for the paintings. “The mathematical models would then become specific personalities featured in Shakespeare plays that would be familiar to his audience and invite curiosity,” Strauss continues.

The Shakespearean guessing game quickly aroused the inner critic of viewers. “We would play games, trying to get people to guess what play belonged to which picture,” Man Ray admitted later. “Sometimes they got it right; sometimes of course, they didn’t, and it was just as well!” Man Ray—Human Equations invites the same guessing with the same ambiguous, same fittingly Surrealist results. By bringing together more than 125 works, the exhibition allows you to take in for the first time ever the original models from the Institut Henri Poincaré Man Ray photographed, the photographs, and the paintings they inspired.

Despite having all the facts before you, however, things never truly add up in a convincing way, just as Man Ray intended, thus calling into question the long-perceived, unjustified differences between “solid” math and the “squishy” liberal arts of literature and painting. For example, on the blackboard shown in Shakespearean Equation, Julius Caesar, writes the illogical equation “2 + 2 = 22” beside rational formulae “a : A = b : B” and “a : b = A : B,” thus introducing us to a whole new world of math merged with art. As exhibition curator Wendy A. Grossman writes in her catalog essay, “Squaring the Circle : The Math of Art,” “Devices such as inversion, negation, doubling, disjunction, and symbolic form common to mathematicians are techniques equally employed by Surrealists in order to achieve the movement’s professed goal of going beyond the real.” If the Surrealists used modern math in pursuit of unreality, Grossman argues, “Is this confluence merely coincidental, or do Surrealism and modern mathematics share something of the same spirit? Or is there something Surreal about mathematics that drew these artists to this realm?”

Just as the idea of modern math and modern art intersecting challenges common assumptions, stirring Shakespeare into the equation adds another intriguing dimension. There’s a long tradition of paintings of Shakespeare’s plays. Shakespeare scholar Stuart Sillars cites in the catalog epilogue William Blake and Henry Fuseli as notable examples, and powerful contrasts to Man Ray’s approach. “Trying to place Man Ray’s Shakespearean Equations series within the tradition of paintings that illustrate or are inspired by Shakespeare’s plays is at once pointless and essential,” Sillars writes, “pointless because the originality and zest of the images, like all his work, argues against such placement, and essential because by comparison the sheer originality of his work becomes clearer.” Despite titling and suggesting Shakespearean qualities, Man Ray’s paintings tell but don’t tell us anything about the plays in a direct or obvious way—a paradox as mathematically modern and as conceptually complex as Shakespeare’s works themselves. The Bard himself would be proud.

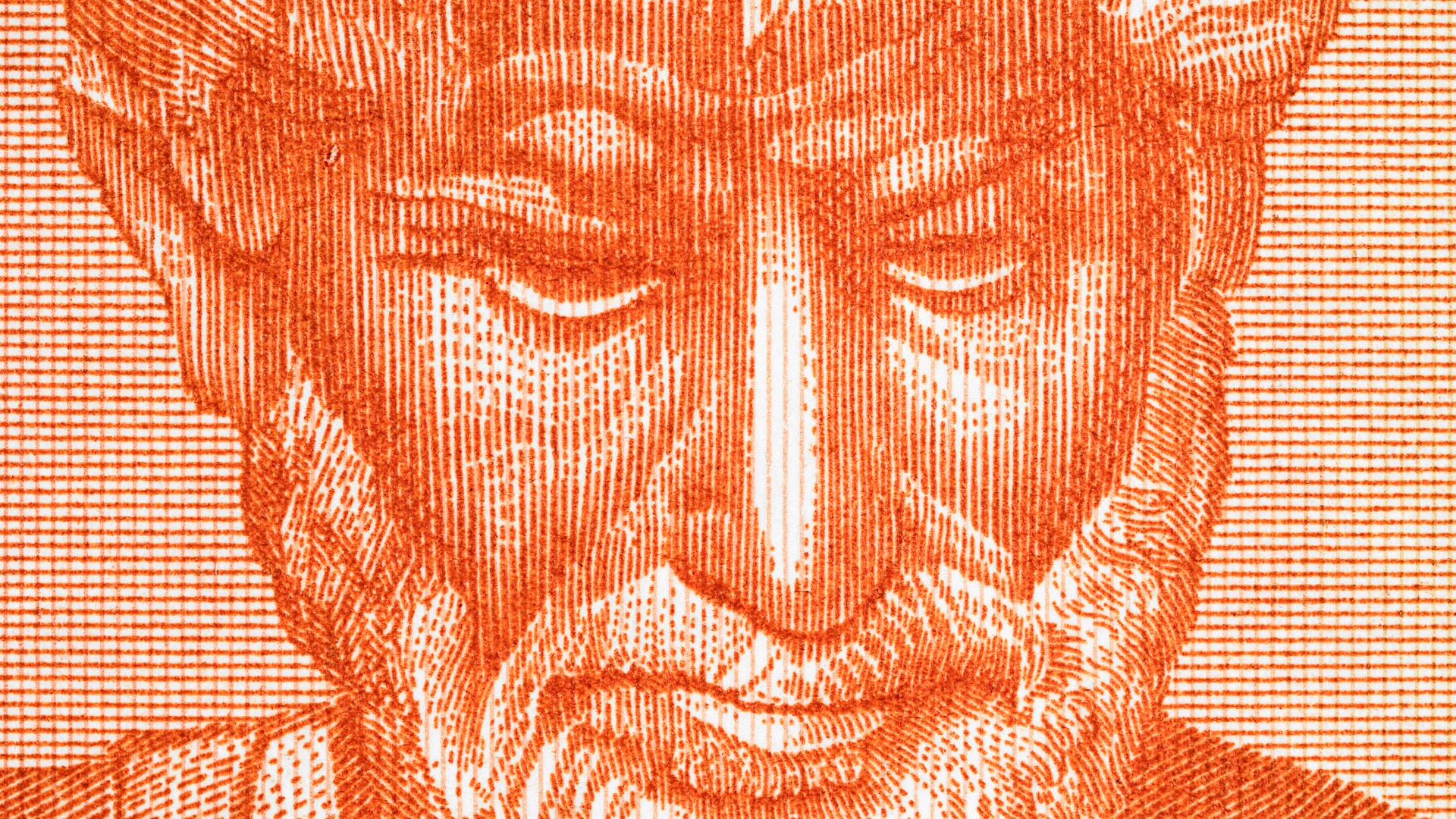

One example of Man Ray’s paradoxical, quintessentially Shakespearean method in action is Shakespearean Equation, King Lear (shown above). Strauss sees King Lear’s famous “tears speech” depicted “by means of a diluted pigment dripping down the canvas” and even suspects that this “presumably fortuitous effect provided inspiration for the choice of title.” Grossman sees Man Ray’s affixing of the canvas to a large wooden hoop—“a geometric figure known to mathematicians as a Kummer surface”—as the artist’s attempt to “turn[] the work into a three-dimensional object that, like so much of his work, defies easy categorization and belies a common perception that his canvases from this series were simply cerebral and literal transfers of his photographs involving little artistic mediating vision.” In essence, Man Ray’s King Lear shows off his mathematical knowledge in the name of artistic independence, all, of course, while depending on a Shakespearean allusion—a paradox neatly holding together right before your eyes. Or, as Sillars neatly puts it, “[H]ere, the Shakespearean equation is the image, not a pedestrian decryption.” As much as you try to solve the puzzle, the puzzle remains bigger and more powerful than any single answer, making this exhibition both frustrating and irresistible.

To accompany these paintings’ first exhibition, Man Ray designed a fittingly different album. On the front cover appeared a yellow, triangular flap with the words “TO BE,” the first half of Hamlet’s famous quote and the most immediately recognized line in all of Shakespeare. Man Ray deflated all expectations, however, when readers lifted the flap to find the words “Continued Unnoticed,” a confession of the artist’s disappointment over the failure of the paintings to reach a wider audience. By bringing these works and Man Ray’s methods to public notice, Man Ray—Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare introduces the artist to the public he’s been waiting for—a 21st century audience more comfortable with the surrealism of post-modern life and accepting of the intersection of math and art in the magical electronic devices it wields. The world of easy answers is gone, even when we have the whole world just a few clicks away. Man Ray—Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare demonstrates that embracing the paradox can be challenging, fun, and undeniably human.

[Image:Man Ray, Shakespearean Equation, King Lear, 1948. Oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 24 1/8 in. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1972. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2015. Photography by Cathy Carver.]

[Many thanks to The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, for providing me with the image above from, other press materials related to, and a review copy of the catalog for Man Ray—Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare, which runs from February 7 through May 10, 2015.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]