Crude Behavior: How Big Oil Tries to ‘Artwash’ Itself

As British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig spewed enough crude into the Gulf of Mexico to be seen from space in late April 2010, the Tate Britain saw fit to celebrate their long-standing sponsorship by BP at their annual summer party. While oil stuck to shorelines and wildlife, the black mark of ecological destruction failed to stick to BP, at least for that night. Artist-activists Mel Evans and Anna Feigenbaum and the Liberate Tate crew crashed that party with performance art protesting both the polluters and those who associated with them. Now, five years later, Evans revisits the relationship between “Big Oil” and “Big Art” in Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts. Evans accuses Big Oil of focusing more on cleaning up their image than their business’ collateral damage and charges cultural institutions that take Big Oil sponsorship money as accomplices to that crime.

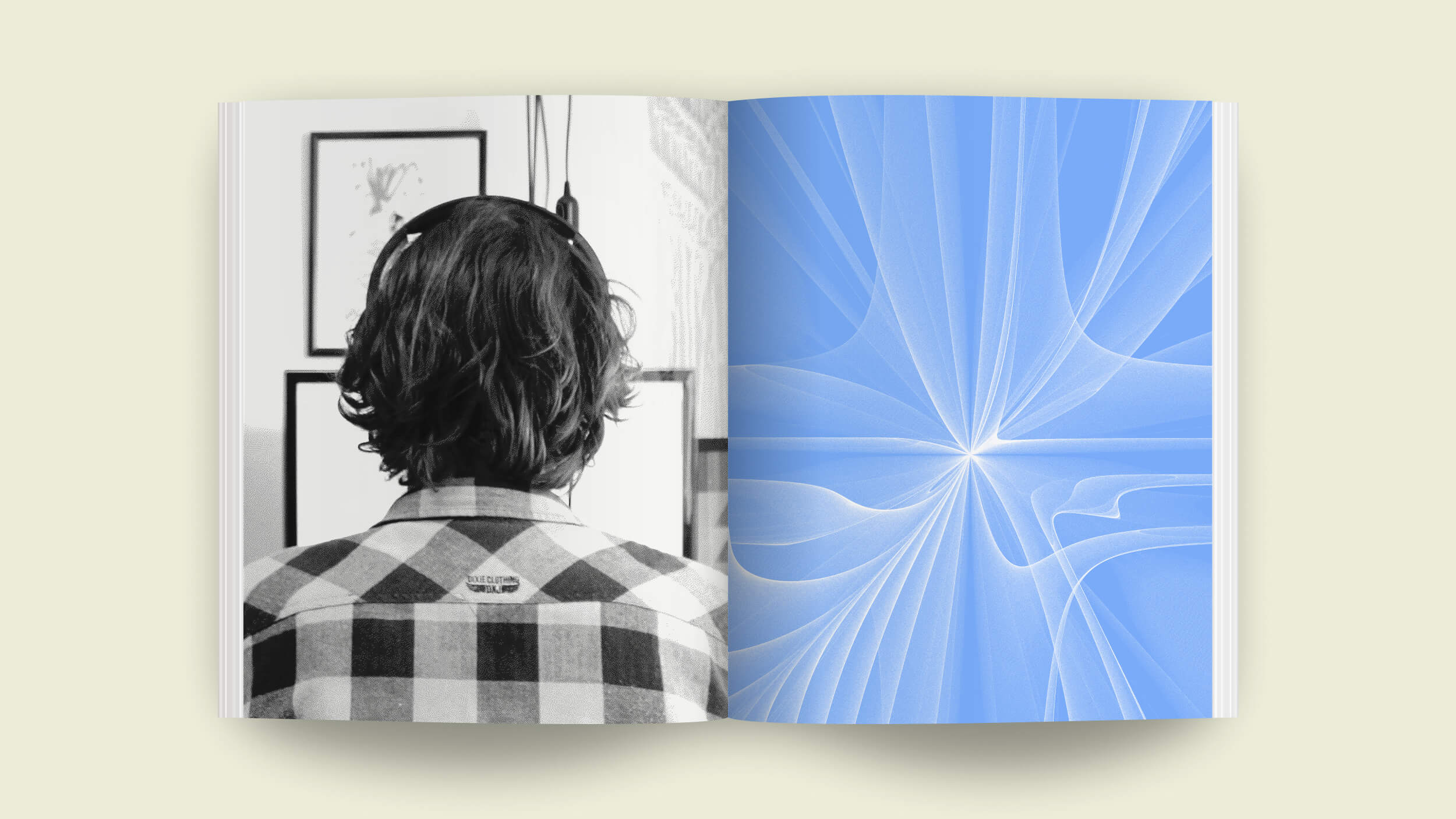

At the Tate summer party back in 2010, Evans and Feigenbaum gashed open bags of molasses “oil” onto the marble floors before donning BP ponchos and failing to contain the “spill.” When Tate personnel surrounded their performance with black screens to cordon off their activism, the women “thanked” the Tate for assisting with the cover-up of their botched efforts — a perfectly ad-libbed touch completing the metaphor of what the party itself was about. Evans coins the term “artwash” from predecessors “whitewash” and “greenwash” to identify this phenomenon. In contrast to the sticky, slippery mess Evans made that evening in protest, Artwash presents a clean, coherent argument that should gain traction with anyone interested in the arts, the environment, or both.

Evans identifies the normalization of a global oil-based economy as a key roadblock to taking on Big Oil. If we all need oil to run the world, then polluting the environment is simply the cost of business, right? “Crude behavior” becomes everyday behavior. Evans argues no. Humanity survived before oil and can survive after oil. “Alternative sources of heat, transport, and power both exist and evolve,” Evans writes in defense of alternative energy sources (which Big Oil and their proxies have gone out of their way to hinder in selfish self-defense). “Oil dependency is a social standard constructed daily by those who benefit from the vast profits made possible by extreme risk and exploitation of land, homes, and habitats,” Evans suggests. Myths such as the “American love affair with cars” fall apart when you look at them as marketing campaigns. Thus, Evans concludes, “[t]he use of oil can be questioned, and so too can oil sponsorship of the arts.”

But who really pays attention to sponsorship? “If the sign had no impact whatsoever,” Evans counters, “it simply wouldn’t be worth putting it up.” Evans masterfully traces how British Petroleum accentuates its “British-ness” by linking itself to the most British of cultural institutions (click to read BP’s own PR links): Tate Britain, the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the Royal Opera House, and the Royal Shakespeare Company. BP never lets the reality of their majority ownership by US banks, institutions, and individuals get in the way of their PR fantasy. Such cultural connections give BP and similar companies “a social license to operate” (as one executive bluntly put it) that really amounts to a “license to spill” (the name Evans et al. gave to their 2010 performance piece). When BP faced its deepest criticism over Deepwater Horizon, the Tate Britain’s then-director Nicholas Serota rushed verbally to its defense, thus providing what Evans sees as “vital solidarity” in the PR war to keep oil dependency the unquestioned status quo.

The standard defense of Big Oil money for the arts as a necessary evil is that cultural institutions need it to survive. In reality, as Evans fully demonstrates with tables and charts, “Oil sponsorship is one small, replaceable thread in the multi-coloured cloth of the organisational incomes of large galleries in the UK, North America, and Europe.” Perhaps the survival argument would float if Big Oil were helping out the little guy in the culture field, but Big Oil only loves Big Art because Big Art can only provide the big PR impact it’s looking for. Evans links this part of the normalizing of oil culture (as savior of the arts) to Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal policies dating back to the 1980s. Thatcher wanted government out of the arts and touted business and the invisible hand of the market as the future funders of culture, even if that invisible hand came covered in spilled oil. Thus, the “Iron Lady,” Evans concludes, “was molding the logic that would inform arts funding debates for decades.”

But why art? Isn’t there an easier and more public way for Big Oil to “wash” its reputation? BP’s sponsored the British Olympic and Paralympic teams to “sportswash” its reputation, but sports doesn’t have the cultural cachet that the arts does. Evans argues that the arts serve as the high priests of the contemporary religion of good taste. Therefore, “[n]othing counterbalances the sins of harmful impacts endemic to the oil industry better than a good dose of holiness.”

In addition to this “saved by association” assertion, Big Oil’s affiliation with Big Art silences artists who would challenge the status quo of acceptance. In addition to censoring or at least blunting the bite of challenging contemporary art focused on the environment, BP logos would provide “an uncomfortable contradiction” in galleries featuring the landscapes of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable or works by ecologically minded performance artist Joseph Beuys. Art dangerous to Big Oil is undermined by sponsorship. One also has to wonder how connected to this sponsored undermining is the undermining of arts education by big business and its proxies. Just recently, UK Education Secretary Nicky Morgan had to walk back negative comments about arts degrees. If an education policy maker denies the value of the arts, then Big Oil (and business in general) has done its self-protective cover-up job far too well.

Americans might read Artwash and its British focus and say it can’t happen here, but it’s already happening. Look no further than The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new $65 million David H. Koch Plaza, or the $100 million David H. Koch Theater (home to the New York City Ballet and New York City Opera), or the $15 million David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History that, according to the website, helps answer the question, “What does it mean to be human?” Would you rather have the oil-refining, climate-denying Koch brothers (who have also funded scientific and educational institutions) or untainted cultural institutions telling you what it means to be human?

As Evans says in a video introducing her book Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts, the movement against Big Oil’s culture-based cover-up is building and just needs “a good shove” to topple BP and other giants over. On the first anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon spill, Liberate Tate reminded people of the human cost of Big Oil’s crude behavior by pouring oil over one of their members curled up on the marble floor of the Tate (image shown above). Art such as Human Cost is exactly what Big Oil wants to control and stop because it could awaken the masses from the petroleum-cultural-government-military complex nightmare we’re all living to our disadvantage and their huge profit. Passionate but never shrill, emotional but precise in her logic, Evans makes a compelling case for arts saving the world from its addiction to oil. If we are to imagine a new world free of Big Oil and its damaging consequences, artists and art—if we let them — will help us picture the way.

[Image:Liberate Tate, Human Cost, 2011. Photo credit: Amy Scaife.]

[Many thanks to the University of Chicago Press and to Pluto Press for providing me with a review copy of Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts by Mel Evans. Many thanks also to Mel Evans and Liberate Tate for providing me with the image above.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]