Comebacks: Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and the City of Detroit

Few American cultural institutions stared as deep into the yawning, austerity-driven abyss of large-scale deaccessioning as The Detroit Institute of Arts. When the City of Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013, vulturous creditors circled the DIA’s collection, estimated worth (depending on the estimator) of $400 million to over $800 million. Some experts see signs of a Detroit comeback, however, but one very visible sign is the new DIA exhibition Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, a showcase of the city’s ties to Mexican artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera as well as a tribute to Kahlo’s and Rivera’s own artistic comebacks. Few exhibitions truly capture the spirit of a city at a critical moment in its history, but Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit is a show of comebacks that will have you coming back for more.

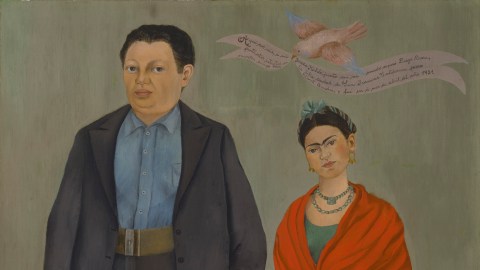

The road to Detroit for Rivera and Kahlo actually begins in San Francisco, where then-DIA director Wilhelm Valentiner approached Rivera in April 1931 about painting murals at the DIA. At the time, Rivera was the most famous (and controversial) muralist in the world thanks to his socialist politics and willingness to express those politics in his art. His diminutive wife, Kahlo, also painted, but few took notice at the time. Works by Kahlo, such as Frieda and Diego Rivera (from 1931; detail shown above), painted the same month Valentiner met with Rivera, drew attention based almost solely on his notoriety. The banner flying over Kahlo’s head announces who she and her husband are and the name of Albert Bender, the San Francisco friend and collector for whom the painting was made. The dual portrait later appeared at a San Francisco “women artists” exhibition, marking the first time the public could see (if not take notice of) Kahlo’s art.

Whereas San Francisco offered some of the Latino culture of their native Mexico for the Riveras, Detroit came as a culture shock. While Rivera kept busy drawing preliminary sketches for the murals in the then state-of-the-art Ford Motor Company River Rouge plant, pregnant Kahlo struggled to find her place in the Motor City. Kahlo’s 1932 painting Self-portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States captures vividly how torn the artist felt between the two worlds as well as how clearly she preferred her native country to what she came to call “Gringolandia.” The loss of her pregnancy during her time in Detroit inseparably associated her life-long physical and emotional agony as shown in the painting Henry Ford Hospital. Kahlo paints her nude body broken and bleeding on a hospital bed clearly marked “Henry Ford Hospital” as Henry Ford’s factories line up across the horizon and assorted objects (her damaged pelvis, the dead fetus, a machine of unknown purpose) hover around her body like balloons attached by thin red strings.

Kahlo frequently left Detroit to go to San Francisco or Mexico during their time there, her presence not nearly as vital as that of Rivera’s. Looking back at this time from a modern perspective, it’s difficult to comprehend her obscurity beside Rivera’s mammoth fame, as if he dwarfed her artistically as well as physically. But in many ways the “Frida” of “Fridamania” created after Hayden Herrera’s landmark 1983 biography begins in Detroit, where Kahlo suffered the most, but also began to channel that suffering into her art. Kahlo’s comeback as a force for feminism and modern art would take decades to happen, but that comeback begins in Detroit.

Unfairly, as Kahlo’s star rose, Rivera’s star sunk. In recent decades, thanks in no small part to the 2002 film Frida, in which Salma Hayek plays the long-suffering, almost angelic title character to Alfred Molina’s philandering Diego. Rivera was certainly no saint, but many still conflate his poor character with his talent. However, even before casting him as a cad, critics slapped Rivera with a Communist label, most strenuously during the “Red Scare” heyday of 1950s American McCarthyism. Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals (which you can virtually “tour” here and here) reflect a short period in American history when socialism found a fair hearing in the wake of the rampant capitalism that led to the Great Depression. Rivera murals combine realistic details of cutting-edge assembly line technology along with sympathetic portrayals of the people working those assembly lines. Such a critique of American capitalism not only in the heart of a manufacturing hub, but also cooperated with and even partially financed (by Henry Ford’s son, Edsel) seems like a fantasy today. The feeling of those years that allowed Rivera’s murals to stand also elected Franklin D. Roosevelt president and welcomed the hope of the “New Deal” that critics also saw as dangerously “socialist.”

To their credit, even in the darkest McCarthyite years, the DIA never destroyed Rivera’s murals, although they did hang a “disclaimer” during the 1950s calling “Rivera’s politics and his publicity seeking … detestable,” but also praising how “Rivera saw and painted the significance of Detroit as a world city.” The disclaimer ended with the suggestion that, “If we are proud of this city’s achievements, we should be proud of these paintings and not lose our heads over what Rivera is doing in Mexico today.” After completing the Detroit Industry murals, Rivera traveled to New York City to paint the Man at the Crossroads mural for Rockefeller Center in New York City at the request of Nelson Rockefeller, who wanted the best muralist money could buy, if not the politics that came with him. When Rivera refused to remove the portrait of Vladimir Lenin from the mural, Rockefeller ordered him to stop painting and destroyed the mural altogether. It is a small miracle that the Detroit Industry murals survive today.

The comeback of the city of Detroit itself would be much more than a small miracle. But thanks to the resilient spirit of the natives as well as DIA’s dogged efforts to cling to the city’s heritage and identity, I’m willing to bet on their success. The exhibition Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit beautifully embodies that comeback spirit on many levels — as the place Fridamania’s birth pains made her posthumous comeback possible, as the home of Rivera’s murals that bear witness once more to his genius, but also as a place where art itself can represent the best that a city once was and can be again.

[Image:Frieda and Diego Rivera (detail), Frida Kahlo, 1931, oil on canvas, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, Gift of Albert M. Bender © 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to The Detroit Institute of Arts for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, which runs through July 12, 2015.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]