Child’s Play: Picasso the Sculptor

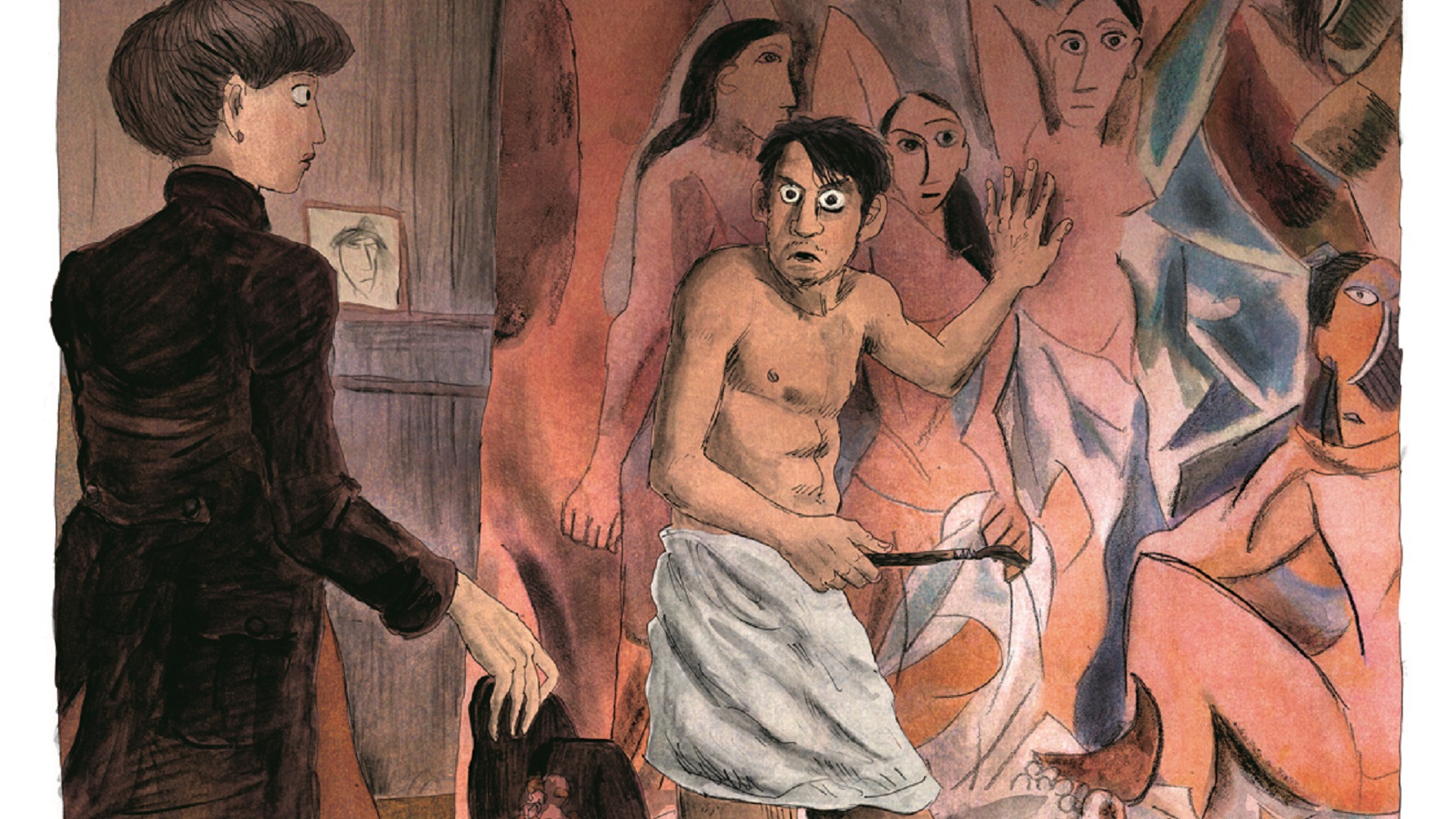

“It took me four years to paint like Raphael,” artist Pablo Picasso famously said, “but a lifetime to paint like a child.” After years of serious training as a painter to learn all the rules of the trade, Picasso pursued for the rest of his life the innocent disregard for rules of a child. That disregard for “the right way” of painting by Picasso gave the world Cubism, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Guernica, and a host of other masterpieces stretching over seven decades in front of an easel. But while Picasso painted for the whole world to see, he also sculpted in private for his own pleasure and edification. Picasso Sculpture, a new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, looks at how Picasso’s innocent, inventive, inner child ran free in a medium he never formally studied — sculpture.

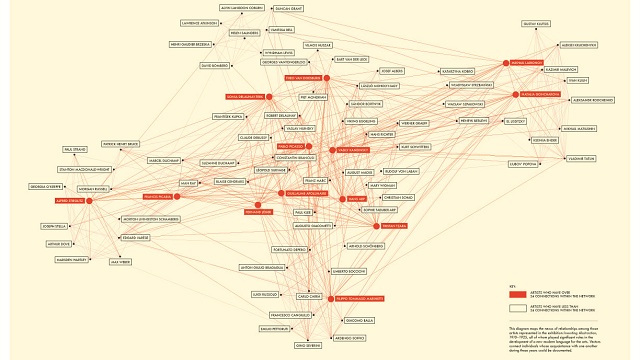

Picasso Sculpture gathers together more than 140 sculptures made between from 1902 and 1964, including 50 from the Musée national Picasso–Paris, the institution that received Picasso’s personal collection upon his death in 1973, which included many of these sculptures that Picasso kept in his home and never publically exhibited. Picasso Sculptures organizes the pieces chronologically, skipping from inspired sculptural period to period, just as Picasso did. The curators identify “Picasso’s commitment to sculpture [as] episodic rather than continuous,” with each gallery or two devoted to “each new phase [that] brought with it a new set of tools, materials, and processes, and often a new muse and/or technical collaborator.” Picasso’s child’s play at sculpture followed childlike whims rather than any kind of set plan.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Glass of Absinthe. Paris, spring 1914. Painted bronze with absinthe spoon. 8 1/2 x 6 1/2 x 3 3/8″ (21.6 x 16.4 x 8.5 cm), diameter at base 2 1/2″ (6.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Louise Reinhardt Smith. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The first galleries hold Picasso’s earliest attempts at sculpture. Looking at Picasso’s earliest sculptures — heavy, solid, and motionless as 1902’s Seated Woman— you can see the first steps of a person with no idea what they’re doing and just mimicking others, but still trying to find his own voice. Many of these sculptures feature then-muse Fernande Olivier and parallel Picasso’s paintings. After a wood-carving phase inspired by African and Oceanic sculptures and then a three-year sculpting hiatus ending in 1912, Picasso’s sculpture and painting finally begin to diverge. In spring 1914 Picasso created six unique sculptures each titled Glass of Absinthe(shown above). Reunited for the first time ever since Picasso’s studio, each Glass of Absinthe features a different ornamental absinthe spoon perched like a hat atop a head-like bronze “glass.” Fun, irreverent, and maybe a little drunk, these sculptures perfectly capture Picasso’s wild Montmatre days surrounded by the intoxicating spirit of creative collaboration.

Image: Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Woman in the Garden. Paris, spring 1929–30. Welded and painted iron. 6 ft. 9 1/8 in. × 46 1/16 in. × 33 7/16 in. (206 × 117 × 85 cm). Musée national Picasso–Paris. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

World War I ended the Montmartre party, unfortunately. Picasso’s friend Guillaume Apollinaire sustained wounds during the war, but died during the Spanish flupandemic of 1918. Commissioned to create a memorial to the poet who helped publicize his earliest work, Picasso struggled to capture the spirit of Apollinaire in sculpture for years. After collaborating with sculptor Julio González and learning from him how to weld metal, Picasso made one last attempt to remember the poet with Woman in the Garden (shown above), an assemblage of salvaged metal welded together and painted white that magically suggests a woman tending to long-stemmed flowers as her metallic hair floats in the wind. The piece literally defies gravity as the lightest of subjects come to life in cold, hard iron. It’s not a portrait of Apollinaire, but it does capture the humor and lightness of his poetry, as well as Picasso’s increasing comfort with expressing his most intimate feelings through sculpture, his “second language.”

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Flowery Watering Can. Paris, 1951–52. Plaster with watering can, metal parts, nails, and wood, 33 11/16 × 16 9/16 × 14 15/16 in. (85.5 × 42 × 38 cm). Musée national Picasso–Paris. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Even when World War II disrupted Picasso’s life once more, he continued to sculpt. When war-driven metal shortages made sculpting in metal illegal in Nazi-controlled Paris, Picasso snuck his sculptures out under cover of night to the foundry. After the war’s end and a brief period of infatuation with classical Greek and Roman sculpture, Picasso began to sculpt using found objects to create increasingly complex works. His use of everyday, domestic objects reflects his post-war return to an everyday, domestic life with new love and new muse Françoise Gilot, who was 40 years younger than the artist. Life with Gilot infused into Picasso’s sculpture a youthful playfulness after war’s weariness, as seen in works such as Flowery Watering Can (shown above). Starting with an actual watering can, Picasso added scraps of metal, nails, wood, and plaster to create a recognizable floral subject, but seen through the eyes of a manchild artist refusing to grow up, grow old, and grow to accept the rules.

Walking through the galleries of Picasso Sculpture, you can’t help but wonder what’s in the next room. The clearly seen impish delight Picasso took in taking newer, different directions in sculpture proves it wasn’t just a diversion from his painting, but a whole new approach to a different medium. Sculpture allowed Picasso to take anything and everything at hand and turn it into art, including transforming torn and burnt tissue paper into the head of a dog or a death’s head or engraving comical faces onto tiny pebbles. SNL poked fun at Picasso as an instant art machine years ago, but it’s important to remember that many of these works were made purely for Picasso’s personal pleasure and were never seen by the public until after his death.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Chair. Cannes, 1961. Painted sheet metal 45 1/2 × 45 1/16 × 35 1/16 in. (115.5 × 114.5 × 89 cm). Musée national Picasso–Paris. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the final galleries we see Picasso’s final sculptural period, marked, of course, by his happiness with his latest and last muse, Jacqueline Roque, subject of over 400 portraits by Picasso and his wife at the time of his death. In a fury of late-career activity, Picasso created over 120 sheet metal sculptures over an 18-month period. Bull (top of post) and Chair (shown above) belong to this final period where Picasso returned to the two-dimensional possibilities of Cubism through sheet metal, but now in the three-dimensional world of sculpture. Despite the two-dimensionality of the sheets, these works invite you to walk around and find new dimensions of meaning. Similarly, Picasso Sculpture invites you to revisit Picasso once again and find new, unrecognized dimensions of the man and the artist, or rather, the man and the child who made art even when nobody was watching.

[Top Image:Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Bull. Cannes, c. 1958. Plywood, tree branch, nails, and screws. 46 1/8 x 56 3/4 x 4 1/8″ (117.2 x 144.1 x 10.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Jacqueline Picasso in honor of the Museum’s continuous commitment to Pablo Picasso’s art. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for providing me with the images above and other press materials related to the exhibition Picasso Sculpture, which runs through February 7, 2016.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]