British Artist David Hockney’s California Dreaming

“[I]t was here that I found a scene that did not exist elsewhere. I suppose I was like a child in a sweet shop. The California beach was like heaven,” British painter David Hockney says in Christopher Simon Sykes’ David Hockney: A Rake’s Progress: The Biography, 1937-1975. The first volume of a proposed two-part biography, Sykes’ first volume follows Hockney—perhaps the most canonically accepted artist alive today—from his humble beginnings in Bradford huddling with his family from the “blitz” to his ascent in the art world and discovery of love and inspiration in a Californian paradise. Written with Hockney’s authorization and cooperation, but not his endorsement, David Hockney: A Rake’s Progress might be the final gesture that cements Hockney’s proper place in the art history pantheon.

Sykes first met Hockney when the author was just 17 years old. “An occasional acquaintance” for years, as Sykes describes their relationship, they lost touch when Hockney moved to California in the 1970s. In 2005, they reconnected and Sykes proposed the idea of a large-scale, multi-volume biography of the artist, who had been the subject of books and films earlier, but never with the same unprecedented depth of detail that Sykes gains from frank interviews with Hockney himself and Hockney’s surviving friends and family.

Sykes paints a vivid portrait of the artist as a child and art-obsessed young man. From caricatures of his siblings to the formative influence of The Goon Show with comedians Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers, you get a fully rounded look at a poor student consumed by a fascination with pictures to the exclusion of almost all else. Although “[m]oney was as tight as space,” in Sykes’ economical phrase, Hockney’s childhood seems the product of a loving and supportive household that may not have fully understood the budding artist in their midst, but always accepted him. Sykes masterfully recounts the standard chaotic rush of influences besetting the young artist—from Hockney seeing Old Masters at the National Gallery on his first trip to London, to the inevitable first face-to-face with Picasso, to the “quirky self-presentation” of the earliest self-portraits, to Hockney’s Portrait of My Father, which Sykes describes as “a touching an sensitive work, over which the ghost of Walter Sickert lingers.” Hockney even chose to wear National Health Service-issue glasses just to emulate Stanley Spencer.

Hockney, however, soon grew restless and challenged the boundaries of his art education. “Seeing the [Jackson] Pollock show,” Sykes writes, “made Hockney realize that his teaching had never addressed the problems of the modern movement, partly, he suspected, because his teachers didn’t really understand it.” As Hockney explains, the Young Contemporaries show that first brought him recognition “was probably the first time that there’d been a student movement in painting that was uninfluenced by older artists in this country, which made it unusual.” Sykes wonderfully captures the energy and experimentation of the early 1960s world Hockney suddenly found himself working and thriving within. Andy Warhol, Dennis Hopper, the Beatles, and a cast of cultural icons from the era all play some part in the panorama swirling around Hockney during this time.

Sykes uses the story of A Rake’s Progress—from the William Hogarthprints Hockney loved and later emulated in his own idiosyncratic take to Hockney’s stage settings and costumes for Igor Stravinsky’s opera on the same subject—as a framing device for Hockney’s own progress both as an artist and as an openly homosexual man. Just as raking light often reveals new textures in a painting’s surface, the raking light cast on Hockney’s art and life from Sykes’ angling prose reveals new dimensions. “Hockney’s outwardly sunny nature concealed a streak of rebellious anger,” Sykes writes in the context of Hockney’s long advocacy for gay rights going all the way back to the 1960s, when then-existing laws could still condemn him for his sexual orientation. Hockney’s In a Dull Village, based on a poem by Cavafy, who was among the first modern writers to openly discuss homosexuality, becomes much more powerful and courageous in this larger context.

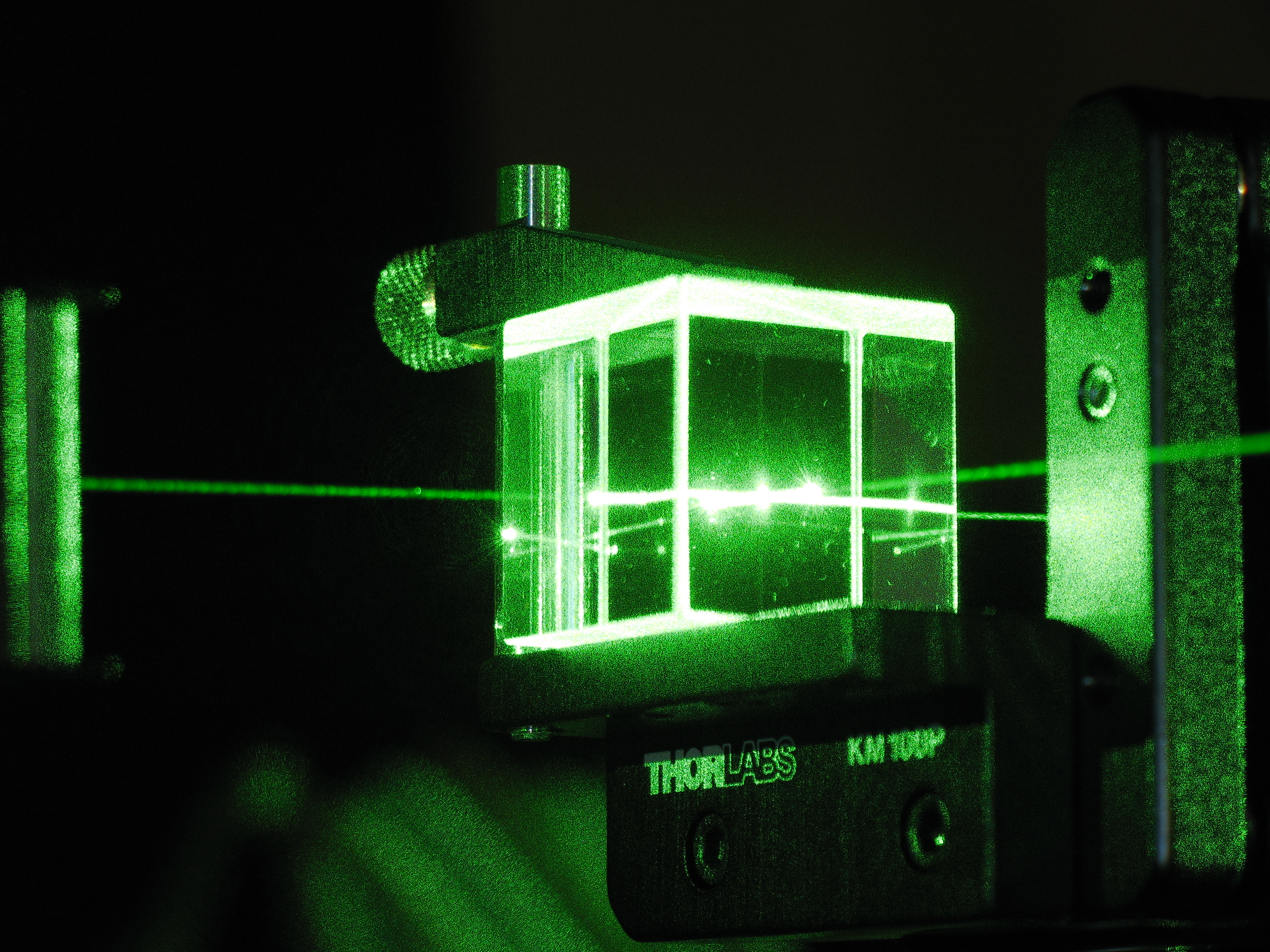

Hockney actually used the money from his Rake print sales to finance his move to California. Prior to arriving, Hockney knew only a fictional California thanks to John Rechy’s novel City of Night. The homosexual community Hockney found there allowed him to express himself more completely than ever before. Sykes also suggests that Hockney also “happened on a golden age in LA, a period when art was all about art and artist, not institutions and money.” All the stars seemed to align for Hockney in California, where his dreams of personal and creative fulfillment appeared on the verge of becoming reality. Fascinated by the sun-drenched, swimming pool culture of California, Hockney painted some of his most memorable works, including 1967’s A Bigger Splash (detail shown above), which Sykes describes as “a mesmerizing depiction of order and chaos.”

Hockney’s California dreaming came to a crashing end with the collapse of his long relationship with the young painter Peter Schlesinger and a stifling sense of creative emptiness. Fortunately, an offer to design sets and costumes for Stravinsky’s operatic version of The Rake’s Progress pulled Hockney from his funk. “For Hockney, The Rake’s Progress was a dazzling success, opening up a whole new artistic world in which he could employ his talents. More importantly, being able to run riot with his imagination had released him from the rut in which he perceived himself to have got stuck,” Sykes concludes, thus finishing the first volume of the biography on a happy, forward-looking note.

I always look at multi-volume biographies as the clincher in terms of an artist’s reputation. If well written and researched, such biographies serve as cornerstones for the later studies that plumb the depths of the subject. Picasso was, of course, Picasso long before John Richardson’s (as yet unfinished) four-part biography, but nobody can study the artist without coming to terms in some way with that monumental achievement. Similarly, Hilary Spurling’s two–part biography of Matisse revealed aspects of the master previously unknown or underappreciated. Once complete, Sykes multi-volume exploration of David Hockney’s life and art may join the first rank of artist biographies. Read David Hockney: A Rake’s Progress: The Biography, 1937-1975 now, before you fall a book (or two) behind.

[Image:David Hockney. A Bigger Splash (detail), 1967.]