A Beautiful Mind: Agnes Martin, Minimalism, and the Feminist Voice

“When I think of art, I think of beauty. Beauty is the mystery of life,” minimalist artist Agnes Martin once explained. “It is not in the eye; it is in my mind. In our minds there is awareness of perfection.” In the first comprehensive survey of her art at the Tate Modern, in London, England, the exhibition Agnes Martin strives to guide viewers to that “awareness of perfection” Martin strove to embody in her minimalist, geometrically founded art. Rather than the cold, person-less brand of modernist minimalism, Martin’s work personifies the warm humanity of Buddhist editing down to essentials. At the same time, surveying Martin’s art and thinking allows us to revisit the feminist critiques of minimalism and shows how Martin’s stepping back from the bustle of the New York art scene freed her to find “a beautiful mind” — not just for women, but for everyone.

Born in Canada, Martin shuttled between New York and New Mexico for much of her early adult life. While studying at Columbia University, Martin heard D. T. Suzuki lecture on Buddhism and considered how to apply his ideas not only to her art, but also to her life. After teaching briefly at the University of New Mexico, Martin returned to New York, where she became active in the art scene in the late 1950s. Artists such as Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, and Barnett Newman became friends, supporters, and influences, but Ad Reinhardt served as her main mentor. Reinhardt specialized in Zen-like, fortune cookie art philosophy such as “Art is Art. Everything else is everything else.” Reinhardt’s 12 rules for pure art included “no texture,” “no forms,” “no design,” “no colors,” “no object, no subject, no matter.” Martin combined in her art Suzuki’s and Reinhardt’s lessons, merging Buddhism and Reinhardt’s pure “Black Paintings” into her own style. When Reinhardt died suddenly in 1967 from a heart attack, just as Martin was receiving her most recognition, she fled the noise and temptations of New York back to New Mexico, where she remained for the rest of her life.

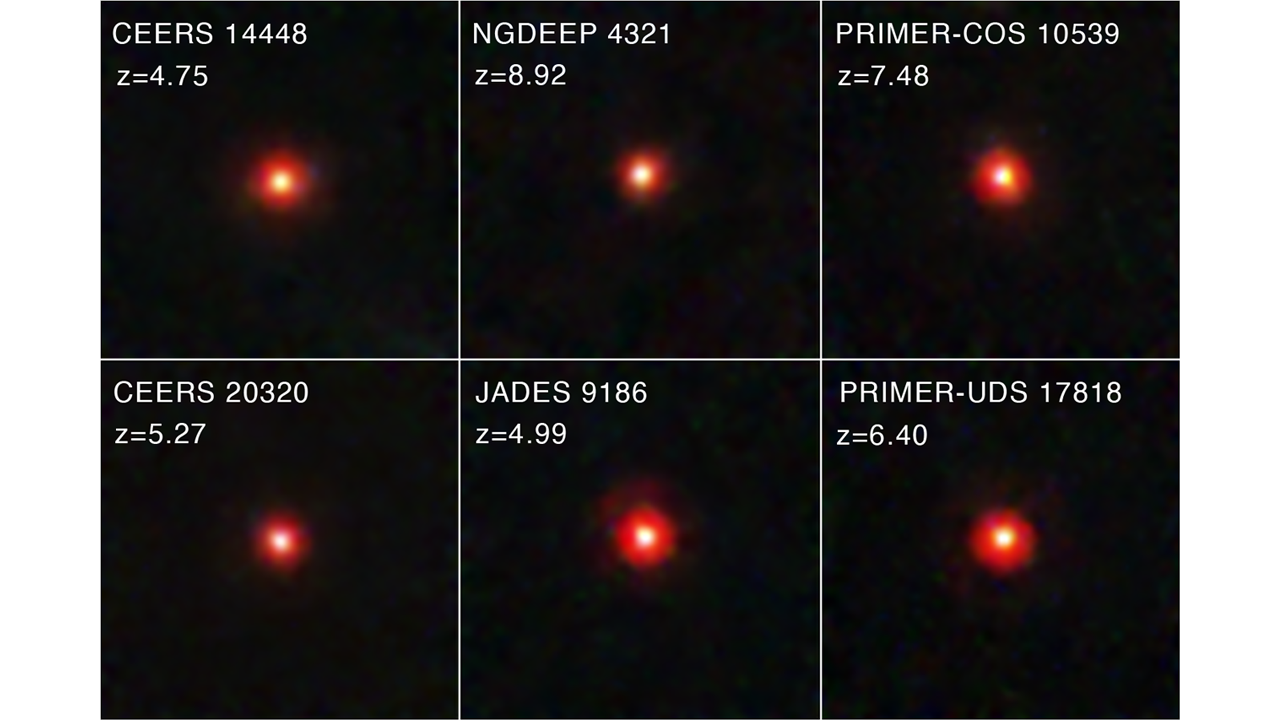

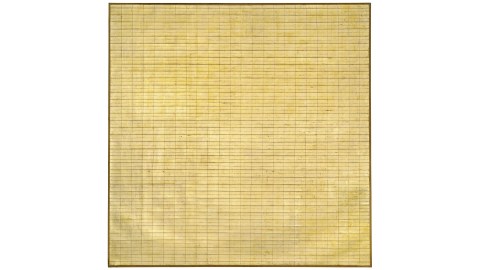

Whereas Reinhardt’s “Black Paintings” continually say “no” in their opaqueness, Martin’s minimalist images say “yes” in their openness. Friendship (from 1963; shown above) presents a simple hand-drawn grid across a gold-leaf-covered canvas. Martin edits the world down to symmetry and geometry — the simplest forms. But rather than dehumanizing, this approach rehumanizes by decluttering the world of all its heart-attack-inducing stress and confusion. You never lose the sense of a human hand making these marks, of a human mind seeking pattern in the chaos. Just as Barnett Newman (a staunch Martin supporter) drew criticism for his deceptively simple images of vertical “zip” lines on canvas, Martin’s deceptively simple grids drew criticism from those who couldn’t see how they reassert the power and presence of geometry by reassuming that geometrical order from the world of modern machines for the world of people. But whereas Newman “unzipped” this order to reveal the heroic in humanity, Martin aims at revealing the simple pleasures of friendship — the human connections she formed with Reinhardt and others. It’s a valentine of sorts, but one you must experience on a deeper intellectual and spiritual level.

In one of those great Zen paradoxes, after the loss of Reinhardt’s artistic friendship, Martin not only moved to New Mexico to find solitude (going so far as to build an adobe house in a remote area), but also stopped making art for six years (while concentrating on her philosophical writing). Martin emerged from these years in the wilderness to create in 1973 a portfolio of 30 screenprints she titled On a Clear Day. Featuring more grids, this time on Japanese rag paper (a clear Zen Buddhist touch), Martin simplified and opened her horizons even more. I can’t help but look at On a Clear Day and hear Barbra Streisand belting out the title tune from On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, the 1970 film made from the mid-1960s musical. Despite the convoluted plot of the film, the lyrics of the song, read in the context of the Martin’s art, clearly strike a kindred Buddhist note:

On a clear day

Rise and look around you

And you’ll see who you are

On a clear day

How it will astound you

That the glow of your being

Outshines every star

Whether Martin had the song in mind or not, she clearly wanted viewers of On a Clear Day to “rise and look around” to both discover themselves and the shining perfection awaiting within.

Martin’s self-imposed exile from the mainstream, New York art scene parallels her distancing from mainstream minimalism, which has often been criticized for its dominance by men and practices that often silenced non-male, minority voices. Minimalism grew as a reaction to the destructive excesses of Abstract Expressionism, which formed a cult of personality around artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. Minimalists stripped away all biography in their art, but in doing so also silenced the identity-based political movements of the 1960s and 1970s, including and especially feminism. The controversy in which minimalist sculptor Carl Andreallegedly murdered his wife, feminist artist Ana Mendieta, became (despite Andre’s acquittal) a symbolic moment for the minimalist-feminist conflict.

Martin’s feminist minimalism stands in stark contrast to other feminist artists such as Judy Chicago (whose The Dinner Party abounds with feminist content and politics) or Frida Kahlo (whose late 1970s/early 1980s posthumous renaissance rode the biographical drama of her work) in that it pares away the politics and minimizes the biography, yet still makes a feminist statement. “To progress in life you must give up the things that you do not like. Give up doing the things that you do not like to do. You must find the things that you do like. The things that are acceptable to your mind,” Martin explains. “Until you can clear up your identity you will be tied to a repetition of this life.” To Martin, editing down life from the errors of the sexist, racist, etc., past isn’t a denial of the problems, but rather a moving forward away from them. Until you recognize and move on, you’re caught in the loop of the past. Critics may say that you can never truly move from the sins of the past, but Martin challenges you to try, to seek that “clear day” where “you can see forever.”

“The measure of your life is the amount of beauty and happiness of which you are aware,” Martin once claimed. The Tate Modern’s exhibition of Agnes Martin calls us to a new awareness of the beauty and happiness in her work as much as the path to a greater awareness of the beauty and happiness in the world itself. The simple geometry of Martin’s work draws us to perceive the simple geometry of human relationships beyond accidents of race, nationality, and gender. Critics of #BlackLivesMatter falsely hear the implied next word as “more” rather than the actual “too.” Likewise, Martin’s feminism says women’s lives matter with a clear, strong, yet minimalized “too.” Martin’s feminism is just part of her larger humanism — another line in the big, interconnected grid of life. The only question that remains is whether we can quiet ourselves long enough to look, listen, and learn.

[Image:Agnes Martin. Friendship, 1963. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to the Tate Modern, London, England, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition Agnes Martin, which runs through October 11, 2015.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]