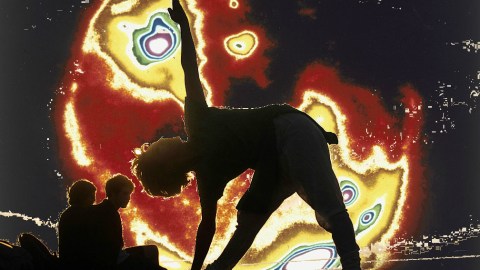

The psychedelic origins of yoga

Image source: WIN-Initiative / Getty Images

The word “soma” is not new. Northern Californians pass over the Bay Bridge into South of Market, its acronym SOMA. More broadly soma was the pleasure drug in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. In that book it worked as an opiate, keeping addicts from questioning external circumstances. The original usage of the word implied something entirely different.

Huxley, a devoted student of Eastern philosophies, knew that. The word first appeared nearly 3,500 years ago in Indian texts. The Soma Mandala is the ninth chapter of the Rig Veda, one of the world’s oldest religious texts. All 114 hymns praise this energizing drink in stark terms. In one hymn, soma is praised:

We have drunk Soma and become immortal; we have attained the light, the Gods discovered.

Soma is the god Indra’s beverage — poets requesting that the drink bless them with divine favor. Expansive language is used: flying through wide-open spaces, touching infinite space, merging with deities. These passages have led scholars to assume that the foundation of soma was amanita muscaria, a psychedelic mushroom that has been used in shamanic and spiritual rituals for millennia.

This theory was proposed by author and amateur mycologist Robert Gordon Wasson in 1968. His co-author, the scholar Wendy Doniger, has since written numerous books on India. The pair drew parallels between the poetic flights of fancy used to describe soma in the Vedas to Siberian shamanic rituals, which use the same mushrooms to create similar mind-expanding experiences.

In her 2010 book, The Hindus: An Alternative History, which ingeniously looks at Indian history and philosophy through the lens of women, Doniger writes about sacrificial soma rituals, common in Vedic times. These texts were written when most citizens lived in the mountains, where mushrooms were abundant. She noticed a textual shift when people moved into early urban civilizations around the Ganges, however. Soma disappeared, replaced by kriyas, purification exercises that informed the earliest instances of yoga.

Mushrooms were gone, but people needed their fix. Without the god-inducing beverage, they began creating intense breathing exercises to alter their consciousness. Yoga was born.

This little sliver of history would remain a footnote if not for a rather intriguing current parallel: both psilocybin (another psychedelic compound found in over 200 species of mushrooms) and yoga are aiding in addiction recovery.

Psychedelics and yoga both came to prominence in America in the middle of the last century. Sure, they were both around earlier, though not mainstream. Finding mushrooms or ayahuasca, an Amazonian brew that is also having positive results with recovery, required trips to Mexico or Peru; yoga was, for the most part, written off as voodoo, witchcraft, or as part of cultish sex rituals.

The discovery of LSD in 1938 coincided with pictures of early yoga poster boy Theos Bernard circulating after the publication of his book on Tibet, Penthouse of the Gods. Writers, artists, and philosophers began exploring inner space through entheogens, a term coined to “generate the divine within,” while Bernard’s contortions appealed to a growing physical fitness culture in America.

These seemingly odd bedfellows are both rooted in the quest for altered consciousness, something humans have been pursuing as long as we’ve been a species. Terence McKenna believed the self-reflective leap in consciousness distinct to human beings was fostered by the very mushrooms brewed by Indian bards four millennia earlier. This quest for “other” states is also at the foundation of early yogic texts, most prominently the Yoga Sutras, compiled by a little-known Kashmiri man roughly 1,600 years ago — also the book that informs all modern yoga — includes an entire section on what you can do when rearranging your consciousness in peculiar ways.

Today kriyas are most prominently practiced by Kundalini yogis, who use these intense breathing exercises to alter consciousness. The epicenter of that movement is in Los Angeles, where a sizable percentage of these white-turbaned yogis are former addicts — drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, the culture of narcissism perpetually rampant in Hollywood. Kriyas leave one feeling recharged and refreshed, filling their brains with the hormones and chemicals to replace the dopamine and serotonin surges their previous crutches provided.

Psilocybin users are having similar success. As Michael Pollan reported earlier this year in The New Yorker, researchers at NYU are seeing breakthroughs in patients enduring “existential duress” during their end-of-life phase. Earlier studies showed like results for those recovering from cigarettes, alcoholism, and cancer. Psychedelics, used for thousands of years in a variety of existential and healing modalities, are finally being scientifically studied in a culture that could use the mental and emotional alleviation they provide.

It’s hard to imagine modern yoga, with its Insta-glamorizing of lithe bikini-clad women and shirtless men posturing on beaches and mountaintops, having origins with Indian sadhus drinking heady brews to mentally fly above those beaches and mountaintops to convene with Indra in the clouds. That’s more a failure of imagination, however. Altering consciousness is an ancient component of our evolutionary heritage. That many are finding both therapeutic in an oversaturated world speaks to our eternal quest for creatively stretching beyond our boundaries. The rituals of old remain our rituals today, still seeking solace outside our skin by being firmly acquainted with the person inside of it.

Correction: An earlier version of the post listed amanita muscaria and psilocybin as the same psychedelic compound.