Scientists Are Scouring Medieval Texts for Ways to Beat Antibiotic Resistance

Scale is sometimes hard to understand. When someone reaches one hundred years of age we often shakes our heads in disbelief, hoping the same for ourselves while trying to mine their secrets. Compare a hundred years against the age of the earth and—you’ve likely heard the one about human existence being a mere second if all of history were stretched to a year.

Before, germ theory and vaccines medicine moved slowly. No serious physician would diagnose based on humors today, though that does not mean Hippocrates was completely misguided. His therapy allowed nature to run its course through the patient’s body, which is terrible advice when considering cancer but effectively all one can do when dealing with colds and flus. Sometimes, as we know, the remedy proves to be worse than the sickness. Humoral doctors also tailored specific treatments to each patient, an emerging practice that’s slowly replacing the one-size-fits-all prescription.

So while romanticizing a pre-vaccine world is for fringe quackery and conspiracy theorists, that does not mean old wisdom is always ineffective. That’s why ancientbiotics, an international group of chemists, microbiologists, parasitologists, data scientists, mathematicians, and other professionals, are scouring ancient texts in search of medicines that stand up to modern scrutiny.

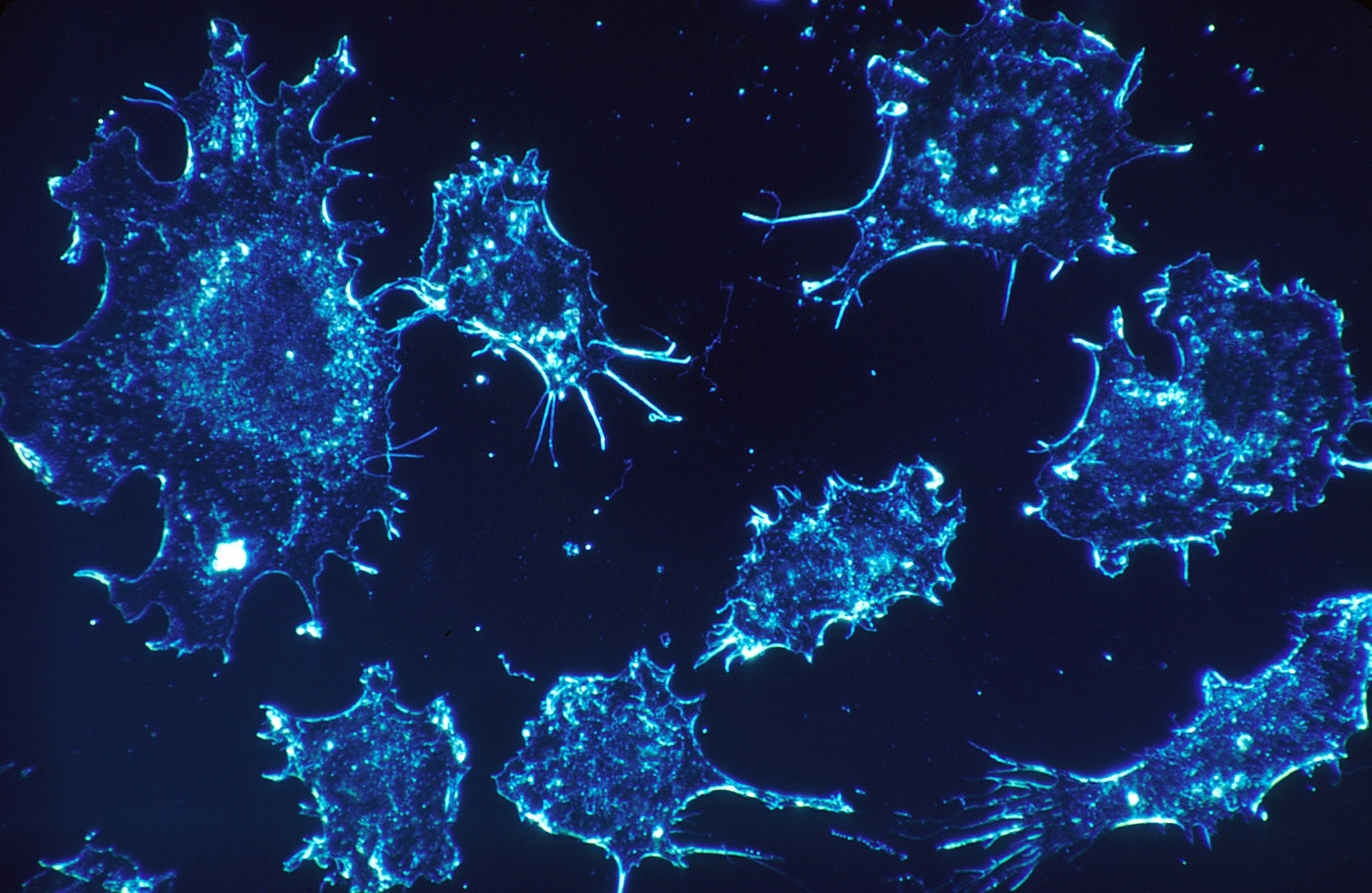

As you are probably aware antibiotics are no longer working so well. Overuse in our bodies (as well as in farm feed) has created super microbial strains that resist our resistance. Seven hundred thousand people die every year from drug-resistant infections. As the University of Pennsylvania’s Erin Connelly writes, if new treatments are not developed such infections will kill ten million people annually by 2050.

And so Connelly and others are creating a database of “medieval medical recipes” in hopes of discovering what wisdom folk cultures really accumulated. I immediately thought of quinine, which has been used to treat malaria for centuries (though the WHO first recommends artemisinin). The Quechua, indigenous South Americans, would swim in lakes by cinchona trees to treat malaria since at least the mid-sixteenth century, though it took French scientists nearly three centuries to isolate and manufacture it.

Connelly discusses Bald’s eyesalve, a thousand-year-old treatment discovered in an Old English medical textbook. A mixture of wine, garlic, onion, and oxgall, the textbook declares the balm must rest in a brass vessel for nine nights before use. As it turns out, the treatment works:

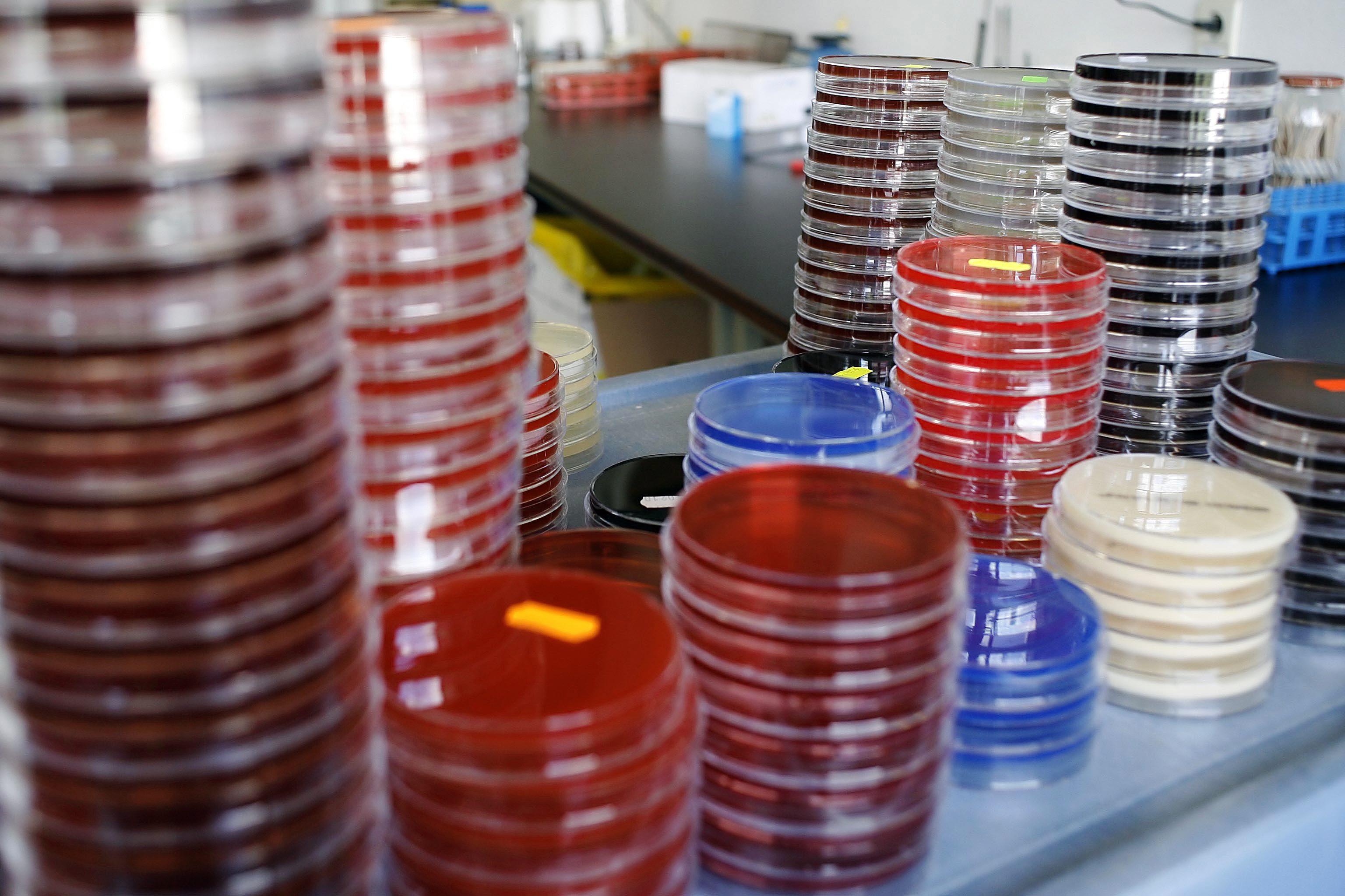

In our study, this recipe turned out to be a potent antistaphylococcal agent, which repeatedly killed established S. aureus biolfilms – a sticky matrix of bacteria adhered to a surface – in an in vitro infection model. It also killed MRSA in mouse chronic wound models.

Connelly writes that part of the challenge is our relationship with the word “medieval” and the “dark ages,” as if no progress was made during that time. While today Chinese medicine is often believed in while lacking credible evidence, Connelly hopes to discover effective antimicrobial agents hidden in medieval texts. Besides, her colleagues are not attempting bloodletting or homeopathy. All remedies are held under intense scrutiny. As she told NPR,

We no longer believe that disease is caused by an imbalance in the humors. But just like in our modern medicine, generations 500 years from now will look back at us and say, how can we trust them? Can you believe the things they used to do? But we know that there is virtue in a lot of the medicine that we do today. We’re sort of looking at the past with that open-minded viewpoint. We don’t want to just accept everything, so we have to use modern technologies in combination with these medieval texts.

For now Connelly is focused on potential agents for treating infections. Her database contains 360 recipes marked with Rx, including treatments like Bald’s eyesalve, which makes the cut due to a combination of ingredients. She’s especially excited to discover how ancient practitioners “designed recipes”—nine nights in a brass vessel might be wishful thinking, or it could take that long for the remedy to increase in potency enough to be effective.

At a time when many medical institutions are hoping to offload your medical problems onto your phone, patience is once again required. In this case it means peering back a few centuries before phones were smart, or existed at all. Our future may just depend on it.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.