How Your Diet Affects Willpower

Willpower is a common tactic in the American mindset. Need to overcome an obstacle? Cure an addiction? Finish a project? The sheer force of mental focus and discipline is what it’s going to take.

Until you get hungry.

Willpower is a real thing; only it’s not dualistic. There isn’t a small you inside of you propelling your body and thoughts forward. Walter White was right: Life is chemistry. If we’re not supplying our bodies with the right chemicals, we’re not going to follow up on our big plans.

In his book, Bulletproof Diet, Dave Asprey — founder of Bulletproof Coffee with butter, something I’m admittedly a fan of — discusses exactly why this is the case. He begins by reminding us that higher-level processes that require our neocortex are more energetically expensive than other neural processes. He writes,

A process like willpower is far more sensitive to your energy than the lower levels of biology needed for survival.

Asprey uses the triune brain model developed by neuroscientist and psychiatrist Paul D. MacLean, a model I’ve employed for years in the movement, music, and neuroscience fitness programs I’ve developed. While not everyone in the field agrees with this assessment, I’ve found it extremely useful in explaining how we prioritize our thoughts and emotional processes. Roughly, it goes like this:

Reptilian complex. The basal ganglia, which MacLean related to our ancient, ancient ancestors. This controls basic movement, procedural learning, many of our regular habits, and, importantly, our emotions. The thrust for survival occurs in this region. When we get “hangry,” it’s our body telling us to get energy quick (even if that particular sensation is the result of carb/sugar overloading). Think of the way a housecat stalks his territory — one of my three guards the litter box like it’s his personal treasure. Reptilian brain aggression at its finest.

Paleomammalian complex. Otherwise known as the limbic system, this region includes the cingulate cortex, which involves the processing of emotions and learning; the hippocampal system, where memories are processed and stored; and the amygdalae, which involves decision-making and emotional reactivity. Asprey calls this our “Labrador retriever brain.” Trouble paying attention and being easily distracted occurs here. It’s also the region that creates our consistent cravings for food. If we’ve grown accustomed to feeding ourselves the wrong types of food, it will always be on the hunt.

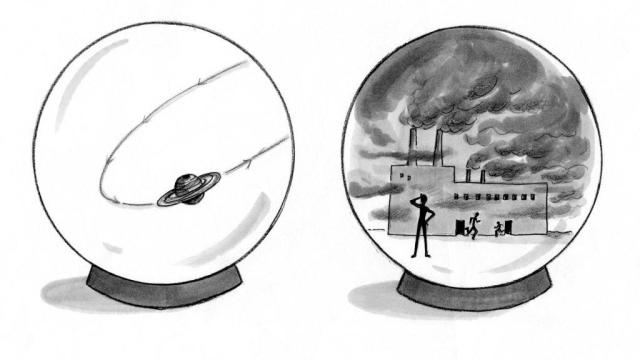

Neomammalian complex. Our neocortex. Evolutionarily the newest region, as well as the area separating us from the rest of the animal kingdom. Language, perception, planning, and perception occur here. When you want to employ a higher-level skill like willpower, the decisions made are being decided in this region.

While our brain, and entire body, is dependent on all other parts, we can simply sketch our brain like a ladder, escalating through the stages of evolution. We ensure survival; we gather resources to guarantee prosperity; we focus on ideals and creativity. Each region needs to be fed properly, which is where Asprey sees a problem.

As you might expect, it comes down to sugar. A little sugar goes a long way, but too much makes addicts of us. Asprey discusses how even seemingly healthy diets work against us. For example, a low-fat, low-calorie breakfast causes your body to secrete insulin, causing a drop in blood sugar levels. Fight or flight kicks in at some point in the late morning or early afternoon, tricking your brain into thinking you need to eat stat. Fight as hard as you like; eventually you succumb, if not immediately, then perhaps for dinner or dessert.

Chowing down on a big breakfast could prove equally insidious — if you’re eating food that’s toxic to you or piling on fruit. If it’s the former, your liver uses blood sugar to oxidize the toxins. Your brain is not receiving proper nourishment, which will again set off fight or flight. The result in both of these cases is that your neomammalian complex goes hungry. At that point, willpower seems like a struggle instead of part of a natural rhythm.

As someone who’s suffered from anxiety disorder and chronic digestive issues my entire life, cutting out grains — carb-heavy foods that turn to sugar in your body — has reengineered my system. Gone are the daily energy crashes and sudden cravings; not one example of anxiety has reared its ugly head. While I’m still new to this process, the results thus far have been stark.

I’m not prescribing nutrition advice; I know how much I loathe people telling me what to do and how to do it. We all have our personal constitutions we need to understand. That said, it took me years of eating the wrong foods to find out what works for me. As soon as I did, my body — and brain — began thanking me immediately.

I was a victim of willpower failures for too long: just one piece of this, just a bite of that. Now, beginning my morning with butter-rich coffee and not eating a high-fat lunch until the afternoon has given me an energetic boost and mental clarity I didn’t know was possible. Once I began feeding my brain what it really craves, the rest of my body became nourished as well.

—

Image: Richard Lautens / Getty

Derek Beres is a Los Angeles-based author, music producer, and yoga/fitness instructor. Follow him on Twitter @derekberes.