Asian philosophies have proven extremely influential in the United States, but are they being interpreted correctly? Frequently not, says Harvard China historian Michael Puett, who focuses on two main ideas in this video: one transported relatively recently to the United States, and another that sheds new light on the so-called naturalistic fallacy.

First up is mindfulness meditation: a practice that has become all the rage for anyone looking to live calmer, more focussed lives. It sounds innocent enough, says Puett, but the goal of distancing yourself from negative emotion presents real risks. If you find a way to cope with negative emotion without changing the material circumstances around you — focusing on internal sources of stress to the exclusion of external ones — you may begin to accept harmful treatment.

This is likewise the case with “finding your true self,” which Puett claims is little more than accepting your circumstances and normalizing potentially destructive patterns of behavior. When we search for ourselves, we search for some authentic, natural self. But putting nature on a pedestal ignores the very real call to action that Chinese philosophy presents.

Michael Puett: Mindfulness is one of the big ideas that’s come in from Asia that’s had a huge impact on America, and basically the idea of mindfulness as it’s practiced in America is one of teaching one to accept one’s feelings. If one feels anger or jealousy, just sort of distance oneself from it, and the goal is to allow one to move through the day not being so taken up by these negative emotions. That seems very powerful but of course the danger of such an approach is that it’s really teaching us not to make any fundamental changes in our life. It’s simply teaching us to accept, and not be so bothered by things, as they occur.

Now Chinese philosophers will, on the contrary, push strongly that, "No, you actually don’t want to be too comfortable with the world as it is, or with interactions as they are or with things you’re doing as they currently are being done." They would say, "Oh no, you should actually be training yourself to respond in ways that can actually affect situations for the better — alter your relationships that really alter the situations you’re in." And I would even add mindfulness, as it was originally practiced, was actually much closer to this idea. It’s really in America that it’s been turned into a kind of acceptance mantra. Whereas a lot of the Asian philosophies — and this is certainly true of China as well — the focus really is on altering, changing. Changing yourself. Changing your actions. Changing the world in which we exist.

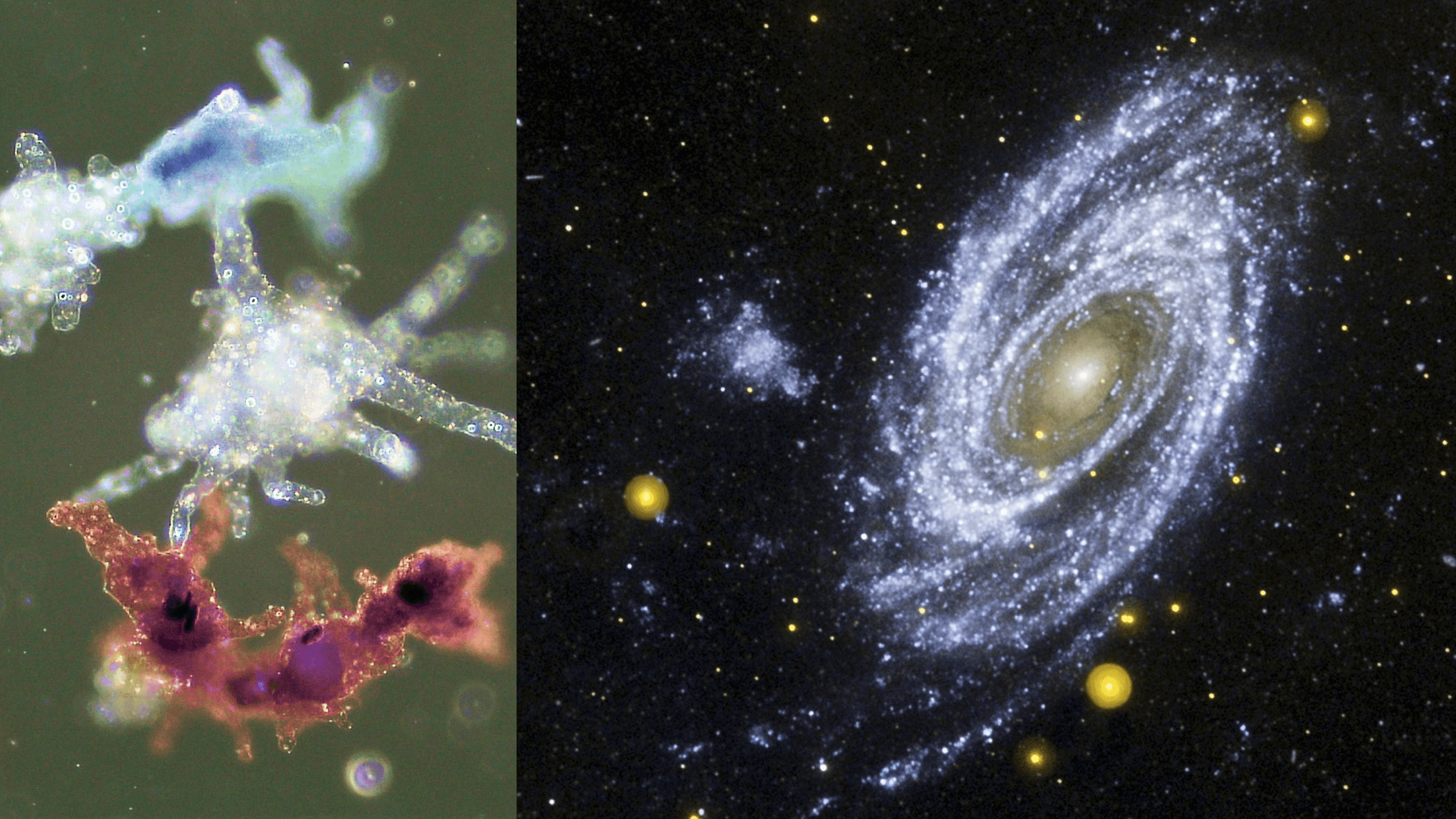

We tend to love the idea of nature. We tend to think that our problem as humans is that we’ve become too artificial, and that we should return to nature in some way. Either return to nature as it exists outside of us — so it means taking a nice walk in a park on a weekend, for example — or returning to our nature within ourselves. So to really stick to who we are, who we fundamentally are, our basic nature that we’re born with, things we’re gifted at doing and really focus on who we naturally are meant to be. Xunzi would argue that both of these visions of nature are actually potentially dangerous.

First of all, let’s begin with the self. The self, sure we’re born with lots of things, but Xunzi would say we’re born with a lot of messy things. We’re born with desires, dispositions, faculties. And we’re all kind of equally born with a bunch of messy stuff. And the focus shouldn’t be on sticking or returning or embracing that stuff with which we’re born. The goal is actually to change yourself, transform yourself. As Confucius will say, 'overcome this self-meaning, this messy self.' And train yourself to be something better than you were at birth. And Xunzi would even make the same point with the larger natural world around us, pointing out that actually most of what we think of as natural is already quite artificial.

There’s nothing natural about a park. This is an artificial attempt by humans to create a seemingly natural space. To which Xunzi would respond that’s a wonderful thing to do, but let’s be aware that we’ve constructed it, and therefore ask the question with a park for example just as we would ask for ourselves, "Have we done a good job of constructing this nature? Have we done a good job of working with this world that we were born into, and the stuff that we are born with?" So his question would always be, 'Don’t return to nature. It’s how you work with things that we are born into, and how you work with the stuff that we were born with.'

The danger of thinking that nature is good is that it restrains us. So I’ll give a very typical example. We often like to think that the way to become a good person is to look within, find one’s true self, the sort of natural self that we have. And once you’ve found that self, that natural thing that you are, the goal is to be sincere and authentic to that true self. So if we stick to what we naturally are meant to be, the gifts that we’re naturally endowed with that’s how we can be a sincere authentic person. Now a lot of our Chinese philosophers would say that sounds good but is, on the contrary, extremely restraining and constraining to what we could do.

The fact is if we’re messy creatures, as many of them would say what we perhaps are in our daily lives are simply people whose emotions are being pulled out all the time by people we encounter, interactions we have, and over time those responses fall into kind of ruts and patterns that can just be repeated endlessly. So someone does something, it makes me angry, and not even because of what they immediately did, but because for some reason it brings back say, you know, someone from my childhood yelling at me, and I just have a patterned response to a certain action being done in a certain way by anyone that brings out a certain response.

So if they’re onto something in this, and I might add lots of psychological experiments show that they really are, then what that means if you try to look within and find your true self — this thing you think you naturally are — what you’re probably finding are just a bunch of patterns you’ve fallen into, many of which could potentially be dangerous for you, for those around you. And if that’s the goal you should be trying to break those patterns, alter those patterns, change the way you interact in the world. And if you’re simply saying, "I should be who I naturally am meant to be," well what you’re probably doing is simply continuing to follow a bunch of patterns probably destructive to yourself and almost assuredly destructive to those around you.