In March 2016, the British Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) decided to crowdsource the name of its new $300 million arctic explorer vessel. It hoped the public would suggest something like ‘Shackleton’ or ‘Endeavor’, but the moment someone suggested the name ‘Boaty McBoatface’, it went viral and shot to the top of the poll. The NERC had the right idea in harnessing the power of crowds, explains Henry Timms, executive director of the 92nd Street Y in New York, but it lacked the skills needed to pull it off. Instead of turning Boaty McBoatface into an opportunity to revive science education and merchandise Boaty, it shut the idea down, canceled the competition and named the ship ‘Sir David Attenborough’. “There’s a set of very clear skills in how you go about harnessing the crowd. And you look around the world right now, any corporation, any nonprofit, any leader who wants to come out on top needs to think a lot more carefully about how they negotiate with the crowd,” says Timms. Here, he shares the four key components of successful crowdsourcing and brand building, and explains how Lego used those methods to pull itself out of near-bankruptcy and up to new heights. Henry Timms is the co-author of New Power: How Power Works in Our Hyperconnected World-and How to Make It Work for You

Henry Timms: So there’s this scientific agency in Britain called the Natural Environment Research Council. They’re a big government body and they’ve got a new ship coming. They’ve got a $300 million new arctic explorer vessel and they’re very excited about it, and they recognize that we’re living in this world of crowds where everyone wants to participate and we’re all finding a way to express ourselves, and they have this idea. They say, "Let’s launch a campaign called #NameOurShip."

Now, this campaign is off to a slightly worrying start because they launch it with a press release, and the press release says, '#NameOurShip. Maybe you, the public, would like to name it something like Shackleton, or Endeavor, or Adventurer.'

Now, these aren’t the kinds of names the public come up with. Within a day someone has tweeted in, “We should call this ship Boaty McBoatface.” And Boaty McBoatface is immediately and virally popular.

I should say that in tenth place—Boaty McBoatface was first, but in tenth place, and I thought this was somewhat neglected, was: 'I Like Big Boats and I Cannot Lie'.

But in any case, Boaty McBoatface does terrifically well. It goes viral. Everyone is talking about it. It’s on all the front pages of the newspapers. There are literally hundreds of millions of Twitter impressions about this. They’re in the pubs, they’re at dinner tables, the whole nation and, in fact, the whole world—it crosses the ocean, it’s covered by The New York Times and CNN—the whole world gets excited and obsessed with Boaty McBoatface.

But there’s a problem. The science minister takes a very dim view of this. 'This is a very big investment of government money. This is not a serious name for a boat. This must be put down immediately and things must be put back in their place.'

And this government agency is in a really tough spot. So, on one hand, they’ve got the public who is incredibly excited about the idea of Boaty McBoatface, on the other hand, the science minister is saying this is not taking science seriously. And they end up, really, in a moment which tells us something about our age, which is what they were trying to do. They were trying to work out, 'Okay, there’s a crowd out there, we want to harness their energy.' They want to do that in a powerful way. They were trying to do that, but they had none of the skills you might need to think about harnessing the crowds.

In the end what they do is they call it ‘Sir David Attenborough’ who is this very famous British scientist, which no one could really complain about too much. And they named one of the small submarines on top of this boat ‘Boaty McBoatface’. So they literally sunk Boaty at sea.

So here’s the question: What could they have done differently? You think about this moment. You think about this huge surge of enthusiasm around science and just imagine if instead of putting Boaty out to the side, instead they leaned into it and they’d said: 'Let’s embrace this. Let’s think about how we could engage a generation of kids in maritime science. Let’s think about how we could merchandise this. Let’s think about all the different moments that Boaty could dock around the nation and you could imagine whole groups of people coming out to learn more about Arctic exploration.'

And they did none of those things. And what that teaches us is, firstly, never ever ask the crowd to name anything. It will always, always go wrong.

But it tells us something else too, which is: there’s a set of very clear skills in how you go about harnessing the crowd. And you look around the world right now and any corporation, any nonprofit, any leader who wants to come out on top needs to think a lot more carefully about how they negotiate with the crowd.

And we see four things that really help organizations and leaders get this kind of thing right. The first is strategy. Do you really need the crowd? This research council didn’t really need any help naming the boat. They already knew what they wanted to call it. So it wasn’t strategic in a very real way.

Number two: Do you have legitimacy with the crowd? There was a famous moment where J.P. Morgan tried a version of this and they did a hashtag campaign called #AskJPM. Now, this was shortly after the financial challenges and crisis and, of course, instead of people tweeting in questions like, “How do I become a banker?”, people tweeted in things like, “How dare you?” and “How do you sleep at night?” So it’s a question around legitimacy. Do you have legitimacy with the crowd if you’re entering this world?

Number three is control. Are you prepared to give up some control to others? What was really interesting about Boaty McBoatface is they weren’t prepared to give up control. As soon as the crowd took this somewhere they didn’t want to go, they shot the experiment down.

If you’re engaging with the crowd you have to honor that crowd, and you have to be able to say, “If you come up with something we don’t expect we will embrace the outcome that you’ve encouraged.”

And then finally, commitment. The fourth thing, which is really important if you want to get this kind of thing right, is are you committed to this in the long term? What we see time and again now is leaders who once a year will “engage with the crowd” and they’ll do some kind of Facebook Live event and they’ll say, “Let’s be open to new ideas.” And then they’ll disappear to their corner office for the rest of the year.

And one of the key things in engaging with the crowd—and you can learn this from anyone, particularly activists who have mobilized—is this is a muscle you have to strengthen day after day after day.

So as we think about how we engage with the world we need to avoid Boaty McBoatface moments, and by doing that find ways of really getting the crowd and getting the value out of the crowd that we can benefit from.

An organization who really got these dynamics right was Lego. So Lego was—I guess about 15 years ago, everything was not very awesome with Lego. They were almost bankrupt. They had spent all this money on theme parks and wristwatches, things were going very badly for the company and they were close to collapsing.

And they recognized—this was just when the Internet was beginning—they recognized there was a group of people out there who had enormous value to offer who they hadn’t previously engaged with, and they were called the AFOLs, the Adult Fans of Lego. And these were people, largely men, who had been building Lego past their childhood, into their adult lives, often in secret, and they all began to realize there were others of them like that around the world. And so as the Internet rose so did this group of AFOLs around the world. And what Lego realized was that these people brought huge value to their brand. So not only were they outspending kids 20 to 1, but they were doing things like creating new sets Lego had never dreamed of or creating whole fan events that Lego had never dreamed of.

And what Lego then did over a decade, which was so smart, is they structured for participation. They built their whole brand around finding ways to invite their crowd to engage with them in meaningful ways. And I’ll give you a couple of examples.

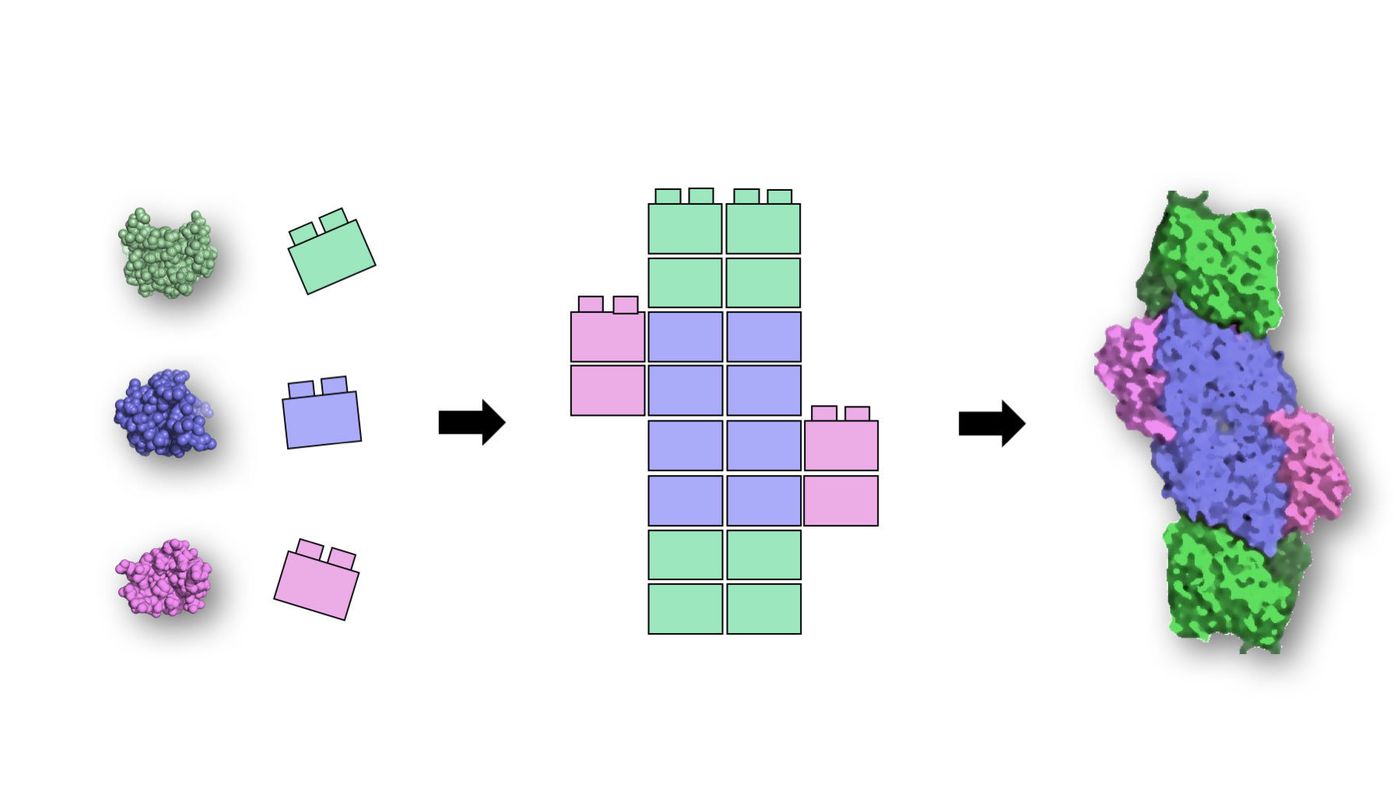

One thing they did even with the recent Lego movie, many of the lines and ideas in the movie were sourced from their fan base. And they did something else too: they opened up their innovation to their fan base. So you now can submit your own ideas for what the next Lego set should be. There was one female scientist who was an AFOL and she had never shown anyone her Lego creations apart from her husband, but she thought that women scientists were very badly underrepresented in Lego so she put together this very cool kit of female scientists and put that forward. Over 10,000 people voted for it. It was hugely successful. It did a great job of doing some great PR for Lego, and that set is now in places all around the world.

And so what Lego teaches is perhaps the key skill of our age, which is: we need to start recognizing that offering agency to our broader community is what’s making the difference between success and failure.

So I think the answer is to think a lot less about hashtags and a lot more around invitations. Because ultimately participation—there are lots of hashtags which don’t work at all, obviously, because what they don’t do is offer people a real genuine chance to participate.

So as you think about the work of building for new power, one of the things to think about is: What am I doing here which will be beneficial to the people I want to engage with? Not, 'What can they do for me?' but 'What can I do for them?'

One of the people we talked to inside Lego—which is a company that's done this very, very well over the years—she always asks herself, the first question she asks herself and encourages her colleagues to ask themselves, is: What am I bringing to the party? What is it that I’m creating that will make my crowd more valuable? Not 'What is it they can do for us?'

I think that power dynamic is actually very important in this work. So, if you’re looking to spread your ideas or start a movement, the first place to begin that isn’t “Here’s my idea, how can more people get behind it?” but “How can I get behind more people?” That’s the right frame.