Who’s Afraid of Beethoven? A Conversation With Joshua Bell

If you run into violinist Joshua Bell at a cocktail party, don’t tell him you find classical music ‘relaxing.’ “Beethoven’s symphonies are not relaxing,” says Bell, who at 45 is director, conductor, and lead violinist of Academy of St Martin in the Fields, where he first performed at the age of 18: “They are the most exciting things that have ever been created by a human being.”

Video: Joshua Bell on why Beethoven’s 4th and 7th symphonies just don’t get old.

I defy you, reader, to dig up or invent an adequate definition of “classical music.” According to Oxford Dictionaries Online, the term generally refers to any body of “serious music following long-established principles rather than a folk, jazz, or popular tradition.” And in the West, strictly speaking, it apparently means: “music written in the European tradition during a period lasting approximately from 1750 to 1830, when forms such as the symphony, concerto, and sonata were standardized.”

“Long established principles”? That’s an 80 year period. And it excludes Vivaldi, Bach, and a couple centuries’ worth of madrigals, operas, and polyphonic church music. It also excludes, at the other end, classically-informed modern and postmodern developments such as Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Duke Ellington’s Satin Doll, and Radiohead’s Kid A. “Serious”? What does that even mean? Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro is about as serious as the 70’s sitcom Three’s Company.

Without impossibly broad terms like ‘classical music,’ or ‘Russian literature’ or ‘Republican’ it would be pretty much impossible to discuss anything or gain any kind of perspective on the vast scope of history and human culture. But because of the way our minds learn, such terms are internalized as cognitive schemata – mental clusters of bits of information around a broad concept that enable us to “get” something in a flash without really thinking about it. Schemas are a useful survival shorthand; you don’t really need to observe the unique characteristics of this particular leopard to know that you’d better run, now. But schemas also account for prejudices (positive and negative) such as “Classical music is relaxing,” “classical music is boring.” Or, “that noise you kids are listening to is not music.”

Video: Joshua Bell on his new(ish) job as director of Academy of St Martin in the Fields.

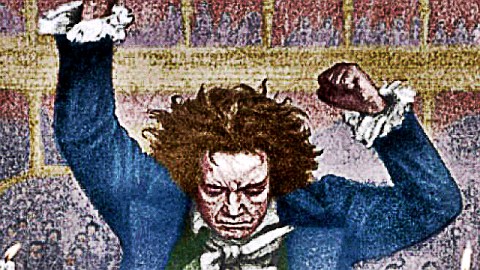

So what happens in your mind when you hear that Academy of St Martin in the Fields has just released Beethoven’s fourth and seventh symphonies, starring and conducted by Joshua Bell? If your experience of Beethoven is more or less limited to that famous, wild-haired, wild-eyed portrait and the da-da-da-DUM opening of the fifth symphony, you’ll think of violins, tuxedos, and, possibly, the word intense. For others, Beethoven’s 7th is “the apotheosis of the dance” (Richard Wagner), the Academy is the most-recorded and one of the best-loved chamber orchestras in history, and Bell’s playing “…does nothing less than tell human beings why they bother to live” (Interview magazine).

Listen to an excerpt from Joshua Bell Conducts Beethoven Symphonies no. 4 & 7, Academy of St Martin in the Fields.

Joshua Bell grew up in a household in which learning about and loving classical music was “like learning to speak. It was just what you did.” He’s heard and played music from the 4th and 7th symphonies hundreds, maybe thousands of times. Yet his enthusiasm in talking about them, and about music in general, is childlike and infectious. For Bell, music – and specifically Western classical music – is obviously a big part of what makes life worth living. It’s a joy he’s made it his life’s mission to share with others.

Which brings us back to cognitive schemas. One of the biggest challenges classical orchestras face these days is in cultivating younger audiences. ASMF is no exception, and as its director, Bell brings a younger energy (one of his main passions growing up was playing videogames) and a willingness to question conventions like the Academy’s white-tie-and-tails uniform:

Which really has nothing to do with the music…It only supports the cliché, you know, that classical music is somehow old and stuffy, which it doesn’t have to be. But playing in venues and experimenting with midnight concerts or jeans concerts or kids concerts, it’s all stuff we’re talking about and I think it’s extremely important.

But you won’t hear Bell conducting over a techno beat anytime soon. His own experience, and the experience he wants for his audiences is that the best of what we call classical music is timeless, revealing something new every time you listen to it. What’s unique about his new recording of Beethoven’s 4th and 7th isn’t that it’s being played on banjos or accompanied in concert by computer-generated projections. It’s that Bell and, under his direction, the musicians of ASMF are telling the “stories” of these symphonies the way they felt them this time around, encountering them in a London rehearsal studio in 2012.

I, for one, who can quote most of Hamlet’s monologues from memory but couldn’t tell a concerto from an overture if you held a gun to my head, plan to clear my mind of bowties, tails, and that crazy-haired Beethoven image and try my very best to hear them.

Follow Jason Gots (@jgots) on Twitter