Four Wildly Different Visions of Canada’s Northeast

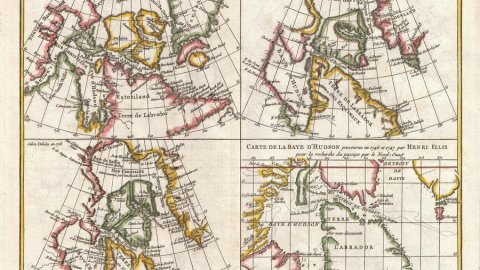

Paris in the 18th century was the hotbed of scientific cartography. But the shape of the Earth’s continents was only as definite as the next explorer’s tall tales. Clans of cartographers bitterly quarreled over how to map the sweep of newly discovered lands, and how to fill in the blanks. This quartet of four contrasting maps on a single sheet is a fossilized reminder of that disputatious era – and a curious, early example of comparative cartography.

This is the Vaugondy-Diderot Map of the Hudson Bay and the Arctic (1772), made by Didier Robert de Vaugondy and first published as plate #9 in the Supplement to Diderot’s Encyclopédie. It was thereafter also published in Vaugondy’s own Receuil de 10 Cartes Traitant Particulierement de l’Amérique du Nord (1779). The legend reads:

MAP representing the different representations made of ARCTIC LANDS since 1650 until 1747, to be compared with the following Map, Plate #10 by Mr. de Vaugondy (1773).

Father and son Gilles (1688-1766) and Didier (c. 1723-1786) Robert de Vaugondy were scions of one of France’s most influential mapmaking dynasties of the 18th century. They were lucky to inherit the map stock of Sanson (cf. inf.), but soon added their own rigorously researched maps to the mix.

Each of the four maps on this sheet shows the same area of North America’s northeast, including Canada’s Hudson, Baffin and Button Bays, the Davis Strait and the coast of Labrador, and a southern section of Greenland. But you have to squint to see the resemblance. The discrepancies between them are huge: the bays and peninsulas are shaped differently, islands present on one map are absent on the others. Some toponyms are still familiar today, while others have sunk into obscurity or have been relegated to the realm of myths.

It would have taken geology millions of years to move and mould land masses to the degree suggested here. It took cartography less than a hundred years, from the mid-17th to the mid-18th century.

The first map, in the top left corner, is an excerpt from Amérique Septentrionale (‘North America’), a map produced in 1650 by Nicolas Sanson, better known for its portrayal of California as an island. Sanson (1600-1667) is often labelled the ‘father of French cartography’. He taught geography to both Louis XIII and XIV as their Royal Geographer, a post to which two of his sons succeeded him.

Sanson’s map places the name Estotiland on the northern part of Terre de Labrador, picking up one of the many phantom names first mentioned on the 1558 Zeno map of the North Atlantic (see also #62). The remarkably pointy northeast coast of Labrador is littered with Dutch names such as Ganse Bay (Goose Bay), and Zuydtoosthoeck (Southeast Peninsula), reflecting earlier Dutch exploration. The westernmost lands are Nouveau Danemark (New Denmark), while a seemingly unattached land (in green) just to the east of it is called New North Wales (refreshing, in light of all the attention South Wales usually gets).

Amérique Septentrionale (1650) by Nicolas Sanson. (Image in the public domain, taken here from Wikimedia Commons)

In the top right corner, a variant of the same geographical area is lifted from America Septentrionalis, produced by Guillaume Delisle (a.k.a. De l’Isle) in 1700 for the Duke of Burgundy. Delisle (1675-1726), who studied under the famous astronomer Jean-Dominique Cassini, was famous for his series of African and American maps, updates of which showing Europe’s evolving knowledge of their geographies. Guillaume was the first to name Texas on a map, the first to map the Mississippi correctly, and the one to finally consign the concept of California as an island to the dustbin of cartography. He too became Royal Geographer (and taught the subject to Louis XIV’s son). And he too was part of a cartographic dynasty: his brothers Joseph-Nicolas and Louis would serve Peter the Great as astronomers and surveyors. The Delisles were great rivals of the Vaugondys.

On this map, the names on Labrador have been thoroughly frenchified, although Delisle acknowledges the persence of Esquimaux. The three separate islands on Sanson’s map have merged into one, possessed of an impressive inlet, the Baie de Cumberland. New North Wales now is a nameless peninsula, on which Cap Confort is the only toponym.

A 1708 reissue by Covens and Mortier of Delisle’s North American map from 1700. (Image in the public domain, taken here from Wikimedia Commons)

The next map, bottom left, is also an extract of a larger Delisle map. His Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France (1703) was the first to correctly depict the latitude and longitude of Canada – the result of 7 years of (desk-bound) research – and would remain the standard for many years to come. It is remarkable for its blank spaces, unknown regions which other mapmakers would have filled with conjecture. Delisle’s scientific rigour drove him to value first-hand, up-to-date knowledge of the features described on his maps, unlike Sanson, who would sometimes knowlingly publish mistakes and outdated facts. However, Delisle didn’t mind hedging his bets by including doubtful features on the map, adding the proviso that their accuracy remained to be established.

Here, Delisle names the island he merged on his previous map James Island (also Île de Jacques), but redivides it into three parts. The Île de Bonne Fortune off the southern tip has disappeared. The Cape Comfort peninsula is still unnamed, but much narrower. The Labrador coast carries the addition: Entrée trouvée par Davis en 1586, a reference absent from Delisle’s previous map. The Passage de Bellisle has been renamed Détroit de Bell’isle, and the island to its south is now named Terreneuve (Newfoundland).

Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France by Guillaume Delisle, first published in 1704. (Image in the public domain, taken here from Wikimedia Commons)

Finally, bottom right, an extract from a 1747 map based on the travels of the English explorer Henry Ellis (1721-1805), who had set out to discover the Northwest Passage – unsuccessfully, as so many before and after him. His expedition got him into the Royal Society, though. After a spell as slave trader sailing on Jamaica, Ellis was appointed governor of Georgia and later of Nova Scotia, when both were still British colonies.

This last map is the only one not using a conical projection, but what looks like a Mercator projection. It is the only one to include Lac Supérieur, one of the Great Lakes south of the Hudson Bay and the Golfe St. Laurent, narrowing to the eponymous river that flows past Québec. Labrador is endowed with a Golfe de Davis on its eastern shore, and a Mer nouvellement découverte (‘Newly Discovered Sea’) on its west. The western shore of the Hudson Bay is shown in great detail, with many bays, capes and rivers named. The phantom island dangling off Greenland’s southern coast looks a lot like Frisland, placed just to the east thereof on the Coronelli map shown in #62.

Nouvelle Carte de Parties, ou l’on cherche le Passage de Nord-Ouest dans les annees 1746 et 1747, Representant la route des Vaisseaux dans cett expedition, Par Henry Ellis. (Image in the public domain. Found here on Rare Maps)

Despite their differences, and their many overlapping accuracies, all four maps share at least one fallacy: each shows the Frobisher Strait dissecting the southern tip of Greenland, placing Cape Farewell, that island’s southern tip, on a separate island. The Strait was named after Sir Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594), sometime pirate and one of the earliest explorers to search for the Northwest Passage. On one of his trips to the Canadian Arctic, Frobisher had mistaken what is now called Frobisher Bay, on Baffin Island, for a strait that might lead to all the way Asia. Somehow, that geographic error was compounded thereafter by moving the Strait to Greenland.

The four maps on the Vaugondy-Diderot sheet contain much more convergence and divergence, truth and error. Explore at leisure, but don’t get lost! For more on Vaugondy mapping the Arctic (but on the northwestern side of the American continent), see #548.

The Vaugondy-Diderot map and excerpts are in the public domain. Found here on Wikimedia Commons.

Strange Maps #692

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].