626 – A Ghost of May Days Past: East Germany Rises Again!

If you’re a cartography nerd, you’re probably also a bit of an election geek. Because nothing beats election night on TV. Exit polls, voting patterns and the results of previous elections are all projected onto maps, and debated until the cows come home.

The framework for each map is the same: the familiar set of national and state borders, and their estranged cousins, the electoral district boundaries. These can be so lugubriously gerrymandered [1] that you understand why they’re only let out on election day, kept behind lock and key at the Institute for Suspicious and Malicious Cartography the rest of the year.

But what keeps mapheads glued to the screen is not those electoral districts, but the constantly varying pattern of primary colours that fill them.

There should be enough political parties to require a rainbow of political colours, but not so many that the mapmakers have to resort to dotted, stripy or cross-hatched fills. Those are the parameters of interesting political cartography – and perhaps also of a healthy democracy.

As the colourful patterns of representative democracy flicker across the screen in wild or subtle variations, they alternate with talking heads who mine them for meaning – cartomancers [2] who conjure victories out of voting patterns, or extrapolate the loss of a single district to a nationwide defeat.

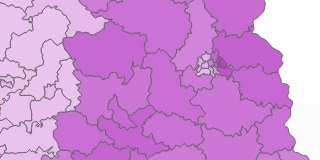

But some electoral maps don’t require analysis. Unprompted by the pundits, they tell a story entirely on their own. The voting pattern they represent manages to resurrect a forgotten fault line, decades or even centuries old. Like this map, which immediately prompts the viewer to freeze frame.

Long time, no see: the DDR resurfaces – on a 2013 electoral map.

Because we’ve seen this map before. It was current for about 40 years, but has been defunct for over two decades. It now belongs in a historical atlas. This is a palimpsest [3], an older map peeking out from under a current one.

This palimpsest surfaced in the German parliamentary elections [4] last month. It plots out the percentages of Zweitstimme[5] going to Die Linke, a party to the left of the SPD, the social democratic party that is the traditional, mainstream leftist force in German politics – and before that in West German politics.

But what it actually, and rather accurately shows is… East Germany! Almost a quarter century after the dissolution of the DDR [6], there it is again: its borders – once so heavily guarded – are crisp and clear once more, exactly where they had been between 1949 and 1990, the year in which East Germany was absorbed by the West [7].

How is it possible that the outline of this failed experiment in ‘Socialism on German Soil’ [8] is still visible after all these years?

East Germany in all its geological glory.

Both the president of Germany and its chancellor [9] were citizens of East Germany. And a generation of Germans now well into their twenties has known nothing else but a unified Germany. And if there was one question dominating the German elections, it was not the East’s place in Germany, but how to deal with Germany’s dominant position in Europe.

Estimates for the price tag of German Unification range from €1.7 and €2 trillion [10]. Far from crippling the German economy, that investment has not stopped Germany from becoming the continent’s economic powerhouse.

But it has also not eradicated the economic imbalance inside the unified Germany. Unemployment in the East is consistently double that in the West (11% vs. 6% in 2012), while the average household income is €7,000 lower (€17,000 vs. €24,000).

This failure to lift East Germany up to the level of the West seems like an echo of a more publicised split in Europe – between the rich North and the poor South. The split also has political consequences: the electorate is more likely to vote for a party that promises to replace capitalism with democratic socialism. That party is Die Linke.

Die Linke came into being in 2007, after the merger of WASG and Linkspartei.PDS – the latter being the successor to the SED, the former ruling party in East Germany. The party’s Council of Elders is still presided over by Hans Modrow [7]. Some elements of its current programme seem lifted straight out of an SED policy paper. Among its foreign policy goals, for example, are the abolition of NATO, the closing of all remaining US bases in Europe, and the creation of a continent-wide security system that would include Russia. Because of their membership of organisations deemed extremist, fully one-third of Die Linke’s current MPs are under observation by the Verfassungsschutz.

Die Linke has managed to make some inroads in the West, winning seats in the regional parliaments of Saarland, Hessen, Bremen and Hamburg. But for the most part, it has fallen below the 5% threshold necessary for representation. Except in the East, where Die Linke has mass appeal. The party even participates in the government of the Land of Brandenburg.

Honecker’s Revenge: a map of where Die Linke is represented regionally.

Consequently, Die Linke profits both from its historic embeddedness in the East, and from the region’s continued economic misfortune. It polled significantly higher in the East, gaining an absolute majority in 4 Berlin constituencies. Since the ejection of the FDP and because it nudged ahead of the Greens, Die Linke, with 64 out of a total of 630 MPs, is now the third-largest party in the Bundestag, after CDU and SPD [10].

Mauer im Kopf: the results for Berlin.

This map illustrates Die Linke‘s geographical dichotomy – the darker hues indicate a score of 14% of over for the party: corresponding exactly with the territory of the former DDR, even in Berlin (which remains split in East and West as to levels of support for Die Linke). The Wall may have been torn down almost a quarter of a century ago, but, as this map demonstrates, die Mauer im Kopf[11] still seems alive and well.

Many thanks to Philip Van Der Veeken and Hildoceras for pointing out this map, found on the website of one of the major newspapers (I forget which). Geological map of the ‘Old DDR’ taken here from Greifswald University. The Berlin map taken from this article on the BBC News website. The map of Die Linke‘s regional representation found here on Wikimedia Commons.

__________

[1] Named after Elbridge Gerry, who in his long and distinguished political career, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the governor of Massachusetts, and Vice President of the United States. Unfortunately for him, his name will remain attached mainly to the herding of likely voters into improbably-shaped electoral districts. See also #53. ↩

[2] Cartomancy is usually understood to mean divination by playing cards, but why not stretch the concept to include maps? ↩

[3] More on electoral palimpsests at #108, #330 and #348. ↩

[4] On 22 September, for the Bundestag, the federal legislative chamber. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s centre-right CDU (and its Bavarian sister party CSU, together called Die Union) won 42% of the votes, and almost 50% of the seats. But as Merkel’s coalition partner, the liberal FDP, sank below the 5% threshold, they are no longer represented, forcing her to look to the socialist SPD or to the Greens in order to achieve a majority in the Bundestag. ↩

[5] In every Bundestag election, Germans get to vote twice. Their Erststimme (First Vote) goes to the candidate they deem the best choice to represent their district in parliament. Half the Bundestag is composed this way, by candidates who got the most votes in each of the 299 Wahlkreise (constituencies) throughout Germany. The other 299 members of parliament are chosen via Zweitstimme (Second Vote), which is cast for the party the voter thinks would best represent the district. Parties get seats in proportion to the percentage of votes they received nationwide – but only if this is more than 5%. If not, they are excluded. This 5%-threshold is meant to prevent the fragmented political landscape that paralysed politics in 1920s Germany. ↩

[6] DDR stands for Deutsche Demokratische Republik, the common local acronym for German Democratic Republic (GDR), East Germany’s official name. ↩

[7] In a last, desperate attempt to spin German Unity as something other than the West’s takeover of the East, the DDR’s leaders proposed that a unified Germany should have a different look and feel from either of its parent states. See for example the title of a book by Hans Modrow, East Germany’s last communist prime minister: Für ein neues Deutschland, besser als DDR und BRD (‘For a New Germany, Better than DDR and BRD’). ↩

[8] Der Sozialismus auf Deutschem Boden – East Germany’s utopian epithet, subliminally encapsulating the communist narrative that the evils of nazism had been overcome by its benign opposite. See also the title of the DDR’s national anthem: Auferstanden aus Ruinen (‘Arisen from Ruins’). ↩

[9] Joachim Gauck, since March 2012; and of course Angela Merkel. ↩

[10] Or $2.3 to $2.7 trillion. Which, to put it in perspective, is only twice the US’s military budget for 2012. ↩

[11] ‘The [Berlin] Wall in the head’. ↩