The Lesson of Barry Commoner, A Social Revolutionary in Environmentalist’s Clothes

“When I was young and bold and strong,

O, right was right and wrong was wrong!

My plume on high, my flag unfurled,

I rode away to right the world.

Come out you dogs and fight! said I,

And wept there was but once to die.”

Dorothy Parker’s wonderful poem about the simplistic passion of the young crusader comes to mind as I think back to the time I met Barry Commoner, one of the pioneers of the modern environmental movement who just passed away. It was 1971, at the height of the Vietnam protest movement, at the beginnings of the modern environmental movement, and I was a weed-puffing long-haired college sophomore swept up in passionate outrage over the ‘The War’ and the National Guard killings of college students at Kent State. I was young and bold and, together with my protesting brothers and sisters, so very strong…and so sure about what was right and what was wrong.

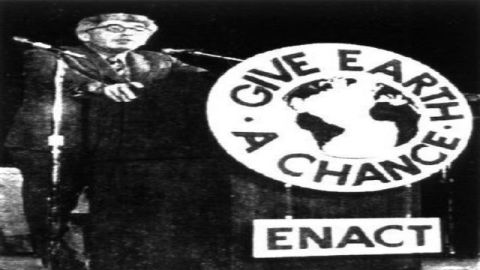

Commoner came to Northwestern to proselytize the new concern about the environment. In those days of rivers that caught on fire (a stretch of Ohio’s Cuyahoga burned in 1969 and made national news), smoke-belching factories, and growing post-Silent Springconcern about industrial chemicals, Commoner was no less than a minor prophet with his deep voice and thick white hair, bow tie and black-rimmed glasses. We showered him with wide-eyed adulation and were inspired to take up the cause. I subsequently rode away to right the world as a journalist, and inspired by that one interaction with Commoner (I don’t recall even speaking with him, just listening), focused my reporting on environmental issues.

But what I’ve learned about Commoner recently also reminds me of the beginning of the next verse of Parker’s poem;

“But I am old; and good and bad

are woven in a crazy plaid.”

As time grants us the gifts of knowledge and wisdom and perspective, we learn that things are usually not as black and white as they first seemed. Commoner’s environmentalism had hidden roots, and deeper goals, than he let on that day (though he spoke about them openly at other times.) His concerns about the state of the air and water and biosphere were actually rooted in an original fear…of nuclear weapons. Commoner was one of many in the early 50’s to launch the global protest movement against nuclear weapons and then the radioactive fallout from the atmospheric testing of those weapons. The fallout risk was actually tiny…the doses were infinitesimal…but fear of cancer and genetic damage from radiation served as effective emotional appeals to alarm people and fuel resistance to nuclear weapons generally. As Commoner once said “I learned about the environment from the Atomic Energy Commission in 1953.” His organization’s influential publication “Environment Magazine” actually began as “Nuclear Information”.

But after helping win international agreements in the 60’s to curtail nuclear weapons programs and atmospheric testing, rather than retiring in victory Commoner transferred his concerns to the related and budding issue of the environment. He just kept fighting, because he was actually fighting for something else, something much deeper, a cause that he never mentioned that day at Northwestern; nothing less than universal social and economic justice.

As the New York Times obituary put it; “Like some other left-leaning dissenters of his time, he believed that environmental pollution, war, and racial and sexual inequality needed to be addressed as related issues of a central problem. Having been grounded, as an undergraduate, in Marxist theory, he saw his main target as capitalist “systems of production” in industry, agriculture, energy and transportation that emphasized profits and technological progress with little regard for consequences…” Those consequences included damage to the environment, a clearer and more universally appealing target for what was a much larger values battle against an economic and power system that Commoner and most of the other founders of modern environmentalism were really attacking.

This remains true today. As Commoner and Rachel Carson did then, Bill McKibben and Greenpeace and many environmentalists do now, rallying people with appeals about threats to the air and water and biodiversity and human health that are at heart values-based campaigns against an economic and social system they feel unfairly puts power in the hands of a few and leaves everybody else powerless and unjustly trapped in rigid hierarchies of social and economic class. (The theory of Cultural Cognition refers to these people as Egalitarians.) While it is absolutely true that the environmental damages produced by this system are real, and concerns about them are earnest and important, it is also true that many environmentalists are waging the same battle Commoner was really waging, a battle not about biodiversity or climate change or air and water pollution but about values and worldviews about how society should work. Environmental issues are just a face for that deeper fight.

Because those deeper values are the informing motivations of some environmentalists, some of them sometimes take positions that are counter to the very goals they profess. Consider opposition to genetically modified (GM) food. Along with safety concerns (essentially unsupported by any reliable evidence even after we’ve been eating the stuff for more than a decade), a prominent environmentalist argument against GM food is that Monsanto happens to make a lot of it, and Monsanto, the GM opponents charge, is a polluting big corporation that uses its riches to influence government and get its way, and is unfair to farmers who have to buy new seeds each year. What does any of that have to do with GM technology or why it should be rejected? Absolutely nothing. But it has everything to do with an underlying motivation of fighting a system in which a powerful few reap a disproportionate share of the benefits while burdening the majority with a disproportionate share of the risks, a system which imposes a rigid social and economic class structure that is not as flexible and fair as environmentalists want it to be.

Consider the effect this has. If GM foods were more widely used a lot of people would be still be alive, or be healthier, and agriculture to feed 7 billion people going on 9 billion would be more efficient, use less water, less land, destroy less soil, demand fewer pesticides…all of which would be good for the environment. But some environmentalists don’t like Monsanto and the system they feel big companies are part of, so in pursuit of their underlying values, they act in ways that are counter to the goals for which they claim to be working.

When I was young, and bold and strong, and naïve and innocent and passionate, Barry Commoner inspired my abiding environmental concerns. But Commoner’s passing reminds me that now I’m old, and the simplistic right and wrong/good and bad of my earlier environmentalist innocence has yielded to the crazy plaid complications of issues like GM food and nuclear power and so many other environmental issues, with tradeoffs that make things more grey than black and white and with their pesky but important qualifying details. And I’m reminded to think a bit more carefully when any advocate urges me to unfurl my flag for a cause, and to think cautiously about what that cause is really about before joining in the chant, “Come out and fight, you dogs.”