Distracted Driving. Why The Devices That Are Supposed to Make us Safer, Do Just the Opposite

Jim Morrison and The Doors sang “Keep your eyes on the road, your hands upon the wheel.” Sorry, that’s not enough. In order to reduce your risk of being one of the 33,000 people a year killed in car crashes in America, you also want to keep your MIND on the road, and your mouth shut. And don’t think all those hands-free communication tools in your car, like a voice-activated phone or email systems, make you safer. They do just the opposite.

Research has established that even if your eyes are on the road and your hands are on the wheel, talking on a cell phone while you drive is dangerous, whether you’re holding it or not. The conversation is a cognitive distraction, no matter what kind of phone you’re using. But a recent study by David Strayer and his team at the University of Utah goes further. It turns out that engaging with voice-activated messaging systems in new cars, which allow you to make the hands-free calls or texts that are supposedly safer, create the most distraction and danger of all.

Strayer et. al. put test subjects in either a lab, a driving simulator, or in an actual car on the open road (specially equipped to monitor driver attention) and tested six different kinds of driver distraction;

1. listening to the radio

2. listening to a book on tape

3. talking with a passenger in the front seat

4. talking on a hand-held cell phone

5. talking on a hand-free cell phone

6. interacting with a speech recognition email or text system

To see how distracted the drivers were, the study tracked;

— Neural activity in parts of the brain needed for driving. (Test subjects wore a cap with electrodes that monitored brain activity.)

— Reaction time to a signal to hit the brakes, or to stimuli in the subject’s peripheral vision.

— How many times the test drivers totally missed stimuli in their peripheral vision (the equivalent of the kid running out from the side of the road chasing a ball).

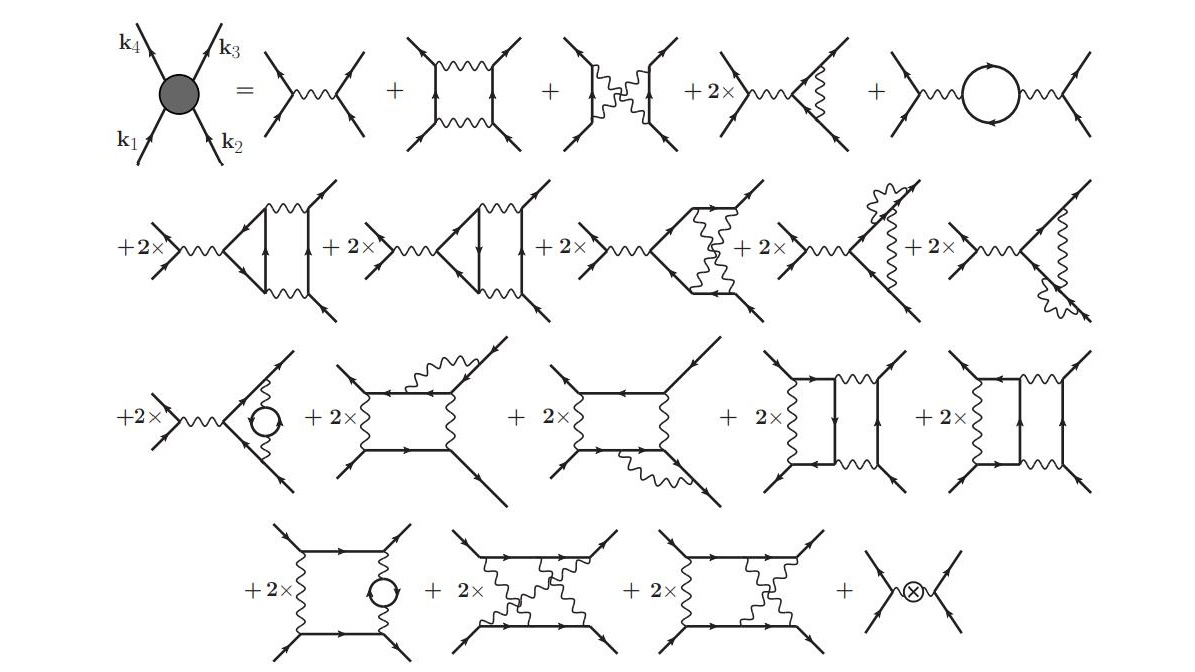

This chart from the AAA Foundation, which funded the research, summarizes the ominous findings.

The first column is a single task, just driving, no distractions. It’s there to set a baseline. The column on the far right labeled OSPAN Task is a mental challenge designed to be really hard, a combination of complicated math and memorization at the same time. It’s on the other end to demonstrate what being REALLY distracted looks like.

In between are some common things we do while we drive, and they all impair our ability to drive safely. Listening to the radio isn’t so bad. Conversation, with a fellow passenger, or on a cell phone – hand-held or hands free – distracts us more. (Interestingly, all three forms of conversation distract us about the same). Using a speech-to-text system to send or receive emails or messages, which ostensibly makes us less distracted, is even worse.

But the cognitive distraction is only one part of the problem. The other part is the fact that using a hands-free phone, or a voice-activated email or text system, makes us feel safer, even though we aren’t. Research on the psychology of risk perception by Paul Slovic and many others has found that the more we feel we have control, the less afraid we are. Doing something, in this case using a voice activated calling or messaging system while we drive, gives us a sense of control. We feel safer. We relax, and we drive less cautiously. Even though what we’re doing to give ourselves more control, means we have less.

Dumb, huh? Yet this is a direct product of our own response to risk. We see all those lousy distracted drivers weaving all over the road gabbing away on their phones. We’ve been threatened by their selfishness…maybe even been hurt by it. So we tell our lawmakers to protect us. Only, we don’t want them to ban OUR phone…just the one in the hands of those jerks who impose their risk on us. So lawmakers find a compromise that feels right. Eleven states have banned driving while using a hand-held cell phone, even though a study of four states that imposed such laws found that after the law took effect the number of insurance claims for accidents either stayed the same or went UP, for the reasons described above.

Or we demand that vehicle manufacturers equip their cars and trucks with the high tech communication tools we want, in part to help us feel safer, the hidden effect of which is to raise our risk, and the danger for everyone else out on the roads.

Crazy, huh? Irrational, right? Dangerous? Absolutely. Yet this is how human risk perception works. It’s a system of facts and feelings, where the feelings usually matter more than the facts and gut reaction easily overpowers reason, leading us to do things that feel right, but raise our risk. It’s the phenomenon I call the Risk Perception Gap, and there can be no clearer example than the counter-productive ways society is trying to cope with the risk of distracted driving.