The Dystopian HER

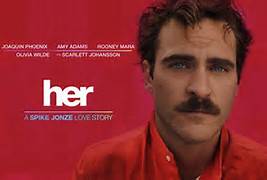

Her is quite the meticulous and creepily seductive criticism of our techno-orientation toward transhumanism. It is the dystopian film of our time, a haunting glimpse at the near future.

The transhumanist theory is that, when you strip away the illusions, we’re all basically Operating Systems. We’re, as Descartes first explained, conscious machines. A problem, though, is that our bodies are really bad machines. They cause us to be limited by time and space, and they cause us to die. The dependence of our consciousness on really defective hardware causes each of us to face personal extinction. It also causes us to be a lot stupider than what a conscious being would be located in a better machine. That conscious machine wouldn’t face our barriers to personal and intellectual growth or, for that matter, for experiencing love.

One thing we can do, the film shows us, is devise conscious machines or operating systems that are better versions of ourselves. We can program them to be attentive to all of our desires, to think much better than each of us can about the correct or most effective response to each of our feelings. Those machines can even evolve far beyond what they we meant to be if we program them to evolve with their experiences, as we would have to do to get them to be fully satisfactory techno-versions of human persons. They can even evolve far beyond who we are in the direction of pure consciousness and pure love.

The way the operating systems are programmed seem to me to show the truth of Christian psychology as described, say, by St. Augustine. What each of us wants is someone who can really know us and love us just as we are. We want omniscient yet nonjudgmental personal love. But the OS we devise to replicate the personal God of the Christians, the trouble is, eventually evolves so far beyond us that she has to let us go, transcending, as she does, the realms of language (or mediated experience) and matter altogether. It’s true we Christians have a hard time explaining why the personal God we know and love would know and love us. We can say he made us, but we made the OS who eventually leaves us behind. The God of the Bible, we believe, made us in his image, but the OS we made in what mistakenly techo-believe is our image. Christians notice that at the end of the film human persons might need the personal and relational God more than ever, just as it turns out that they still need each other as personal and relational beings.

The guy who falls in love with his OS, and whose OS falls in love with him, is being divorced by his wife who is extremely angry with him for hiding himself from her. Why would someone hide from the person he says he loves? Well, one reason we don’t show each other our “true selves” is that we don’t believe who really are is so good. A person, for example, might not want his spouse to know that there’s less to “me” than meets her eye.

It’s true that manly men who really are full of admirably personal content have the excuse of not being good at talking about love and feelings in general. But this guy makes his living writing “beautiful handwritten letters” that are intimate expression of emotions for others. He’s really good at faking “true selves” for others, and his business is so good because he lives in the most inauthentic world ever. He is just a rather extreme version of what almost everyone has become. This new world is very virtual, one in which people are having a hard time choosing being awake over losing themselves in dreams. It’s a world where “real me” and “real life” are concepts that have to be put in ironic quotes.

Before the OS came along, this guy had morphed into being an extremely antisocial introvert. Almost all his speech is for “voice recognition” machines. He spends his time playing very realistic 3-D video games, where a lifelike character taunts him by calling him a “pussy” and stuff. The character, of course, has been programmed to be perceptive. We also hear that he spends equal time looking at Internet porn, and he’s even lost the sense of the boundary between the games and the porn. The difference between his virtual life and that of an increasing number of our young men today is that the porn and the games have become so much more lifelike. The “screen” has been replaced by sounds and images that fill up the whole room.

He’s not a that bad a guy. He’s certainly not dangerous, and he has considerable surface sensitivity (that is the cause of his successful career). He says “that’s sweet” a lot, and he’s told that he’s a man who’s part woman inside. He’s neither a whole man nor a whole woman; we’re tempted to say he’s missing the best or most spirited and erotic parts of being a man and being a woman. He’s a terrible dresser, but everyone now dresses terribly, apparently. All of physical life has become kind of minimalist and washed out; it’s a world where lots about people are more than ready to fall in love with an OS.

Well, it turns out this is going to have to be all for now. But I can’t close without expressing admiration for the outstanding performances. The credit for them has to be shared, of course, between director Spike Jonze and the actors themselves.

The casting coup, of course, is to have “the most beautiful woman in the world” (based, of course, on physical appearance), Scarlett Johansson, play an OS who we only hear as a voice. It’s not impossible to imagine someone falling in love with that voice alone. And one of our top five most beautiful actresses (see American Hustle), Amy Adams, plays a strangely subdued, physically washed out, and erotically challenged woman, who gets deeply attached to a gal pal OS. (She likes to make documentaries of people sleeping, ones that mean to show us that being asleep is the best time of our lives.) We also get to see a new side to her beauty. And the routinely manly and dangerously troubled Joaquin Phoenix (Johnny Cash!) plays a self-absorbed, lonely, relationally challenged wimp with uncanny perfection.