This is Your Brain on Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s literary career, which spanned a quarter century roughly between the years 1587 and 1612, came at a time when the English language was at a powerful stage of development. The great fluidity of Early Modern English gave Shakespeare an enormous amount of room to innovate.

In all of his plays, sonnets and narrative poems, Shakespeare used 17,677 words. Of these, he invented approximately 1,700, or nearly 10 percent. Shakespeare did this by changing the part of speech of words, adding prefixes and suffixes, connecting words together, borrowing from a foreign language, or by simply inventing them, the way a rapper like Snoop Dogg has today. (Another exemplary instance is the way HBO’s series The Wire has integrated slang into our contemporary vernacular.)

What’s the Big Idea?

In the past, most brain experiments would involve the study of defects, and use a lack of health in the brain to show what it can do. Professor Philip Davis from the University of Liverpool’s School of English is approaching brain research in a different way. He is studying what he calls “functional shifts” that demonstrate how Shakespeare’s creative mistakes “shift mental pathways and open possibilities” for what the brain can do. It is Shakespeare’s inventions–particularly his deliberate syntactic errors like changing the part of speech of a word–that excite us, rather than confuse us.

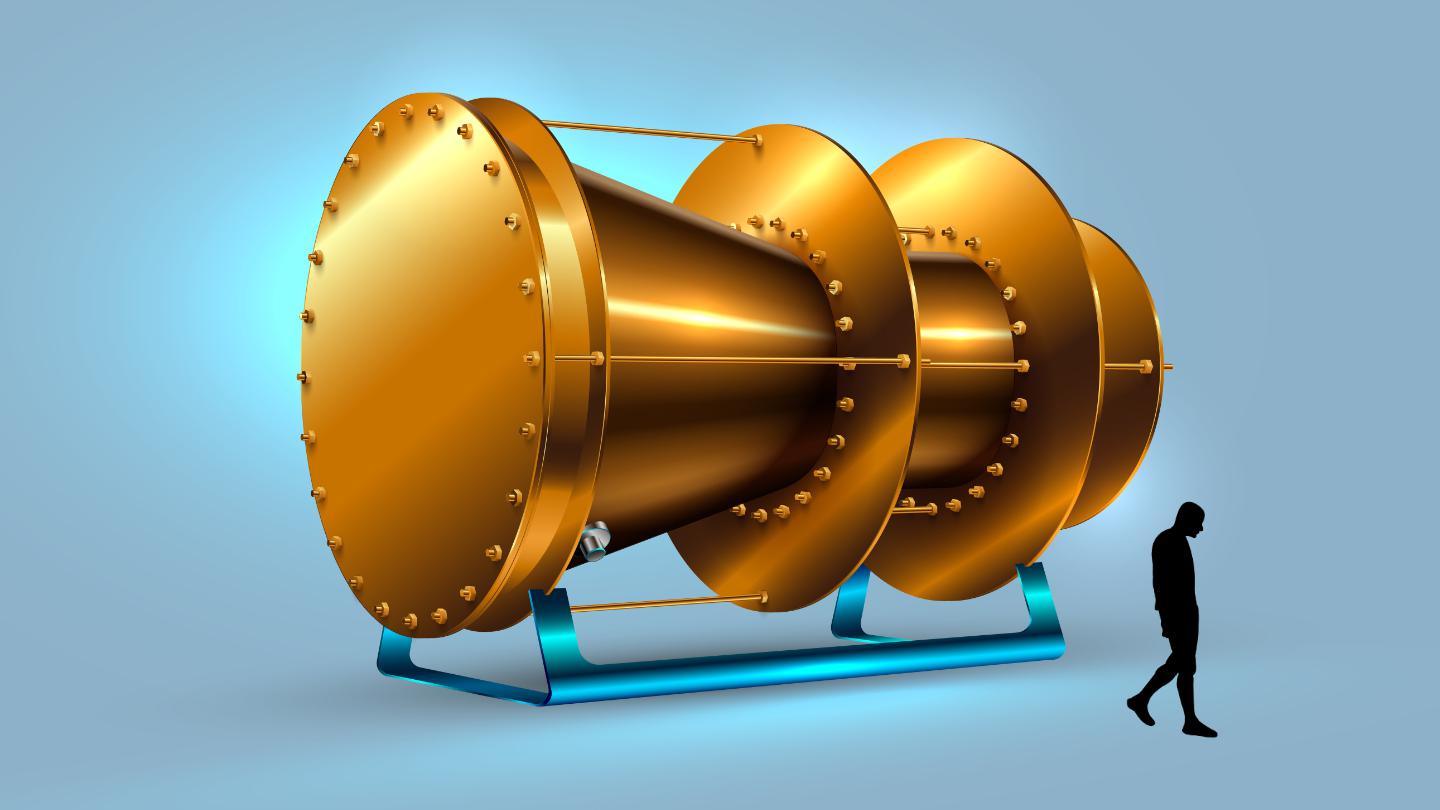

With the aid of brain imaging scientists, Davis conducted neurolinguistic experiments investigating sentence processing in the brain. The experiments showed that when people are wired they have different reactions to hearing different types of sentences.

One type of measured brain responses is called an N400, which occurs 400 milliseconds after the brain experiences a thought or perception. This is considered a normal response. On the other hand, a P600 response indicates a peak in brain activity 600 milliseconds after the brain experiences a quite different type of thought or perception. Davis describes the P600 response as the “Wow Effect,” in which the brain is excited, and is put in “a state of hesitating consciousness.”

It should be no surprise that Shakespeare is the master of eliciting P600s, or as Davis told Big Think, Shakespeare is the “predominant example of this in Elizabethan literature.” The visualization of the experiment looks like this:

But how is poetic language different from normal language? Consider these examples, in which Shakespeare grammatically shifts the function of words:

An adjective is made into a verb: ‘thick my blood’ (The Winter’s Tale)

A pronoun is made into a noun: ‘the cruellest she alive’ (Twelfth Night)

A noun is made into a verb: ‘He childed as I fathered’ (King Lear)

As Davis’s experiments have shown, instead of rejecting these “syntactic violations,” the brain accepts them, and is excited by the “grammatical oddities” it is experiencing. While it has not been fully proven that we can localize which parts of the brain process nouns as opposed to verbs, Davis says his research suggests that “in the moment of hesitation” brought on by the stimulative effects of functional shift, the brain doesn’t know “what part to assign the word to.”

What is the Significance?

For Davis, we need creative language “to keep the brain alive.” He points out that so much of our language today, written in bullet points or simple sentences, fall into predictability. “You can often tell what someone is going to say before they finish their sentence” he says. “This represents a gradual deadening of the brain.”

Davis also speaks of the possible applications for his research on other fields, such as treating dementia. “My hope is that we find ways to treat depression and dementia by reading aloud to patients.”

And yet, Davis is a literary scholar first and foremost. He argues the heightened mental activity found in the brain responses to his experiments may be one of the reasons why Shakespeare’s plays have such a dramatic impact on readers and audiences. What is at the heart of Shakespeare, he says, is the poet’s “lightning-fast capacity” for forging metaphor that created “a theater of the brain.”

Lesson:

Short of placing multiple electrodes on your scalp, simply read the four sentences below, and ask yourself which one you like best.

1. A father and a gracious aged man: him have you enraged

2. A father and a gracious aged man: him have you charcoaled.

3. A father and a gracious aged man: him have you poured.

4. A father and a gracious aged man: him have you madded.

If the experiment worked, here are how the results should have played out: The first sentence should elicit a normal brain reaction. The brain recognizes that the sentence makes sense; unlike the second line, which the brain rejects. The third line (“charcoaled”) measures both N400 and P600 responses, because it violates both grammar and meaning, and is gibberish. The fourth line is an example of functional shift, which is found in King Lear. Your brain is now thinking like Shakespeare.

Follow Daniel Honan on Twitter @DanielHonan