How do We Choose our Mates? The Big Bang Theory vs. the Algorithm

Love is an epiphany. Maybe that’s the sweetest romantic dream of all. By the big bang theory of mate selection, our soul mate is out there somewhere, and they’re going to hit us like a ton of bricks one day, while we’re in line at Target, turning the street corner, or riding Amtrak.

Nat King Cole sang the big bang theory best:

I was walking along, minding my business,

When out of an orange-colored sky,

Flash! Bam! Alakazam!

Wonderful you came by!….

One look and I yelled TIMBER!

Watch out for flying glass….

I went into a spin and I started to shout, ‘I’ve been hit. This is it, I’ve been hit!’

According to the big bang, we don’t select a spouse. We discover them.

A variation is the romantic chaos theory: an invisible hand of the (erotic) market guides us to Mr./Ms. Right through a sociobiological brew of pheromones, adaptive preferences, and other mysterious but irresistible forces of attraction that only look chaotic from afar.

The post-romantic mood is different. It favors mate selection with screening instruments, marketing formulae, detailed questionnaires and algorithms.

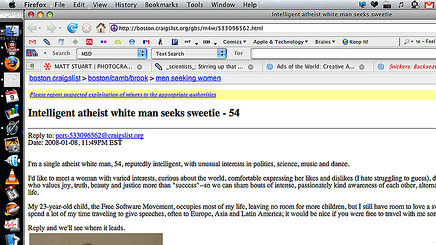

I remember from my adolescence when the personal ads ran ignobly in free city newspapers, one category removed from escort services and listings of places to sell sperm and platelets. Now, they’re mainstream, especially online. According to research out of MIT’s media lab, over half of American singles use online dating services and personal ads.

We also unapologetically and enthusiastically use matchmaking services, to go about the business of love. “Maybe it’s time to outsource your dating life,” an ad for the successful matchmaking service, It’s Just Lunch, advises. “Great guys and women don’t circle around your block waiting for you to come out of your house” (tell that to Nat King Cole!). “You’ve got to market yourself.”

Marketing yourself and “taking a professional approach to finding [your] compatible match,” they explain a la mode, means telling the matchmaker what you’re sure you want, and sure you don’t want, and won’t consider. Then, the clients can “go out on dates with someone who already meets their essential requirements.” The search for “chemistry,” the ad says, can proceed from a pool of pre-selected, chemistry-worthy candidates.

This on-paper screening and culling of the herd may be a better or worse dating style than what came before, or qualitatively just the same.

Whatever the case, the pre-screening does reinforce the decades-long trend toward “assortative mating.”

More than ever, like marries like. We’re marrying people with the same education, earning potential, career paths, and background. In the 1940s and 1950s, it was more likely that someone could “marry up” out of their class.

For my book, I read a month’s worth of wedding announcements in the New York Times and my hometown newspaper, and discovered not only assortative mating, but hyper-assortative mating on steroids. It wasn’t just that the college-educated married the college-educated. They tended to choose spouses from colleges on almost the exact same “tier” of selectivity according to the U.S. News and World Report’s ranking system. And spouses frequently married someone with exactly the same advanced degree.

We’re profoundly socially niched. That’s Bill Bishop’s point in The Big Sort, and the same applies to marriage. We marry ourselves, people more like us by key criteria of education, earning potential and career.

Second, pre-screening instruments replace the big bang theory with a more rational process, curve-fitted to our perception of our ideals. They eliminate people with qualities that we’re absolutely sure we don’t want—our “essential requirements.”

My husband and I joke that we’d have never selected each other at match.com. He would have screened me out because I’m not an athlete. I would have screened him out because he was an athlete; or, more precisely, because he wasn’t a funky creative type, since I was “absolutely positive” that’s what I wanted when I was 30.

There’s the dilemma. Because a new research study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology finds that while we thinkwe know what we want, we don’t. Researchers found that when looking at written profiles, participants expressed more interest in candidates who fit their “ideals.” But in live interaction, the ideals were no longer correlated with romantic interest.

Pre-screens are based on the idea that we can know what we desire in the first place. This research suggests, however, that what feels like an ironclad essential is more like a mushy maybe.

Think about your single life. In addition to my husband, here are some of the people that I liked and had meaningful, charming relationships with, who didn’t meet an essential requirement and would have been pre-emptively eliminated on Zoosk:

I’m not much of a romantic. Or a Luddite. Still, this list does make me nostalgic for those chaotic, in-the-flesh mixing pots—any place where maybe, just maybe… “Flash! Bam! Alakazam!” a totally inappropriate, bizarre, and essential-requirement-flouting person gets chosen, and loved.