Not every disagreement is a logical fallacy

This article originally appeared in the Newton blog on Real Clear Science. You can read the original here.

All too many people behave as if they are experts in everything. The internet is partially to blame. The widespread availability of information is both a blessing and a curse. Indeed, the adage “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” has never been more true, especially as it has become painfully obvious that some people believe that reading the first paragraph in a Wikipedia entry will quickly bring them up to speed on complex topics. Really, who needs a PhD when you have five minutes to kill and access to Google?

Philosophy, in particular, has witnessed an obnoxious infestation of alleged experts. World-renowned physicist Stephen Hawking — who has weighed in on everything from aliens destroying Earth to the existence of God — recently declared that “philosophy is dead.” How he is able to simultaneously practice philosophy while believing that philosophy is dead without experiencing cognitive dissonance is curious, but perhaps Dr. Hawking suffers from the philosophical equivalent of Cotard delusion.

The esteemed Dr. Hawking isn’t the only person who has foolishly dabbled in philosophy. Several bloggers, specifically science and political bloggers, have made dubious contributions to the philosophical subdiscipline of logic. How so? By inventing logical fallacies (that you would never learn in a real logic class) and applying them to their political opponents.

The most popular one is false equivalence. (I wrote an entire chapter debunking false equivalence for my book, Science Left Behind — now available in paperback at fine retailers everywhere!) From what I can gather, “false equivalence” is a fancier way of saying, “You’re comparing apples and oranges.” It’s meant to convey the notion that two things being compared can’t actually be compared.

In reality, this argument is used mostly by political hacks who are trying to rationalize hypocritical beliefs and behavior. For instance, readers of RealClearScience know that both sides of the political spectrum — Republicans and Democrats — will throw science under the bus whenever it is politically convenient. But partisans don’t see it that way. In their minds, only the “other side” is unscientific, and any comparisons between the two sides immediately draw accusations of “false equivalence.” Some writers have built their careers peddling this nonsense.

Outside of political bickering, another newly invented fallacy is called sunk cost. According to psychologist Daniel Kahneman, “We are biased against actions that could lead to regret.” This explains why, for instance, students finish their PhD’s even if they realize they don’t really need one anymore.

But how is that fallacious thinking? Regret is a powerful emotion. Nobody likes feeling regretful. Additionally, many people enjoy finishing something they started. Proving one’s ability to persist in the face of adversity could instead be interpreted as a positive character trait.

The growing list of fallacies goes on and on. Some are legitimate, but others are questionable. After reading the list, however, it is difficult to imagine how anyone could ever form an argument that wasn’t fallacious!

The trouble with labeling everything a “fallacy” is that (1) not all poor reasoning is automatically fallacious, and (2) it implies that everybody would agree on everything if we could only think correctly.

Consider the following: Your child tells you that she wants a lollipop before bedtime. You, the supposedly enlightened adult, know that a dose of sugar for a toddler before bedtime isn’t the best idea in the world. So you ask, “Well sweetie, why do you want a lollipop now?” She responds, “Because I want one.” There’s nothing wrong or fallacious about her argument. It is, however, very poor and immature reasoning — something we would expect from three-year olds or, perhaps, college students. No matter how many hard facts you use to convince her that you’re correct, your little princess is going to disagree.

Why? Because people differ in priorities and value judgments. What is important to me isn’t necessarily important to you. What your daughter finds important (a lollipop) isn’t the same as what you find important (a good night’s sleep and smaller dental bills). Fundamental differences in beliefs and values will forever prevent humanity from coming to 100% agreement on anything.

Blaming our disagreements, particularly political ones, on logical fallcies does nothing other than delude us into thinking that our opponents are illogical and that we are intellectually superior. And since when has that attitude ever succeeded in convincing anybody?

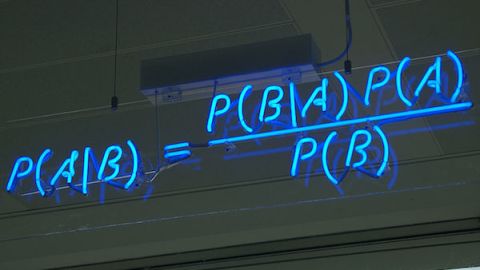

(Image: Bayes’ Theorem via mattbuck/Wikimedia Commons)