How Our Minds Work = Hard To See

How our own minds work is hard to see. Here are some once-tempting views about why we do what we know we will rue:

1. Mythmakers like Homer imagined us at the mercy of gods and fate. What isn’t achievable by will and effort is a gift of the gods (even sleep). And the strong emotions of our inner lives seemed like external spirits possessing us.

2. Reason-loving Socrates reportedly believed that we never knowingly do wrong. Ignorance causes vice. Knowing what’s right = doing it. That’s untrue, but still influential (~more information = healthier eating).

3. Plato compared the mind to a two-horse chariot: Reason (the charioteer) steers the horses (emotions), one good (naturally virtue-seeking), one bad (appetitive, unruly). All three must cooperate to reach rational goals.

4. Aristotle blamed “weakness of will” which enabled emotions to master reason. Well-being required the opposite… reason must master (well trained) emotions.

5. Saint Paul confessed, “I do not understand my own actions… For… I do the very thing I hate.” He blamed “the sin that dwells within me.” Augustine went further, projecting his own psychodrama onto everybody by inventing universal “original sin.” Avoiding sin was hard, so “lead us not into temptation” became desirable.

6. The Enlightenment enabled new metaphors, like Hume’s “The mind is a kind of theater.” And thinkers recast minds as moved by impersonal science-like forces. Locke (called the “Newton of the mind”) imagined we are gravitationally attracted to pleasure, which we weighed against pain. Behaviours seemed driven by utility maximizing calculations (see “Bentham’s bucket error”).

7. Economics remains possessed by Socratic and Enlightenment spirits (better information begets better calculated behavior). And practices “flaw enforcement”… markets systemically encourage (rather than resist) temptation, envy, and greed.

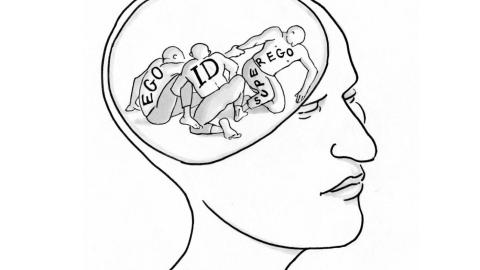

8. Meanwhile Freud’s subconscious wrestlers (id, ego, superego) remain influential beyond reason. Like Augustine, Freud over-projected his own demons. Adding an unample sample of case studies, his unfalsifiable unscientific stories of repressed hydraulic drives and dark irrational impulses, keep mythic spirits alive within our skulls (e.g. the Oedipus complex which Frued imagined explained much human behavior).

9. Nowadays scientific psychologists are (re)discovering and empirically measuring our everywhere evident (throughout experience, history and the arts) un-rational-ness: Emotions are fast thinking. Minds have kludgey “cognitive biases.”

What to make of, or add to, the above?

a) Many evidently aren’t prudent, so is avoiding or promoting temptation wiser?

b) Unconscious influences aren’t all Freud’s demons or psychophysics. The logic coupling basic drives to behavior is script-like and culturally configured.

c) Self-command remains rationally adaptive, Plato’s reins must bridle unruly vices (or we reason no better than id-centric children, see Plato’s pastry and Freud’s Reality Principle).

d) We evolved to habitually act without consciously thinking. Aristotle was correct, we must train our emotions (fast thinking) and habits (automatically unthinkingly triggered behaviors).

Or our fate is to live irrationally.

Illustration by Julia Suits, The New Yorker Cartoonist & author of The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions.