Bradbury, Borges, and the Future of Media

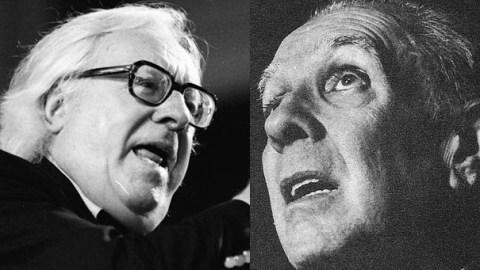

Who knew that Jorge Luis Borges, the great Argentine fiction writer and maestro of high literary culture, was a Martian Chronicles fan? Now that you know, doesn’t it seem fitting? In Borges’s Selected Non-Fictions I came across the following tribute to Ray Bradbury, who died this past week at 91:

What has this man from Illinois created—I ask myself, closing the pages of his book—that his episodes of the conquest of another planet fill me with such terror and solitude?

How can these fantasies move me, and in such an intimate manner? All literature (I would dare to answer) is symbolic; there are a few fundamental experiences, and it is unimportant whether a writer, in transmitting them, makes use of the “fantastic” or the “real,” Macbeth or Raskolnikov, the invasion of Belgium in August 1914 or an invasion of Mars. What does it matter if this is a novel, or novelty, of science fiction? In this outwardly fantastic book, Bradbury has set out the long empty Sundays, the American tedium, and his own solitude, as Sinclair Lewis did in Main Street. [“Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles,” Eliot Weinberger trans.]

I don’t think Borges ever commented on Fahrenheit 451, but I wish he had: it makes for fascinating reading beside Borges’s fictions. Bradbury’s most famous book imagines a dystopia in which books are systematically burned. Late in life, the author pegged this nightmare to a specific interpretation: it wasn’t about censorship, he said, but the replacement of books by television. He imagined a world in which books were first stripped down to their bare “factoids,” then junked altogether in favor of “a proliferation of screens.” He feared the destruction of precious texts, precious culture.

In his own stories, Borges gave us the nightmare of texts proliferating out of control, such that the best are not destroyed but lost in the shuffle. He captured this idea through a variety of related images: neverending books (“The Book of Sand”), infinite libraries (“The Library of Babel”), labyrinths (just about every Borges story). A librarian who suffered from deteriorating eyesight, he dramatized both his private anxieties and a mounting twentieth-century sense of information overload. In the futuristic universe of “The Library of Babel,” the book destroyers have already come and gone—and haven’t made a dent:

Their name is execrated, but those who deplore the “treasures” destroyed by this frenzy neglect two notable facts. One: the Library is so enormous that any reduction of human origin is infinitesimal. The other: every copy is unique, irreplaceable, but (since the Library is total) there are always several hundred thousand imperfect facsimiles: works which differ only in a letter or a comma. Counter to general opinion, I venture to suppose that the consequences of the Purifiers’ depredations have been exaggerated by the horror these fanatics produced. [Andrew Hurley trans.]

Both authors’ prophecies were spot on. The Web has overtaken TV as our dominant mass medium, but while it’s partly text-based, it’s much better at chopping up, scattering, and recombining texts than preserving their integrity. It hasn’t ended the dominance of visual media or the decline of print books (Bradbury himself finally consented to a Fahrenheit 451 e-book last year), but it does churn out more text per day than anyone could sift through in a lifetime. It’s Borges’s nightmare linked to, or spliced with, or embedded within Bradbury’s.

At the same time, both prophecies were pure fantasy. The Web, unlike TV, is not a medium constrained by a finite number of programming hours. It’s capacious enough to offer both a universe of stupid factoids (or if you prefer, cat videos) and a universe of serious, long-form texts. It also makes information far more navigable—and thus less overwhelming—than it ever was in the days of card catalogs and microfilm. A simple search algorithm could have tamed the Library of Babel.

Still, the future isn’t over yet. In a book culture increasingly dominated by an electronic device called the Kindle, and freshly divided over plans to create a “universal library,” both Bradbury and Borges will be wearing their prophets’ mantles for a long time to come. May we never lose the worlds they created, and never be lost in them.