Perceptions of Science: Hubris and Public Distrust

–Guest post by Kathrina Maramba, American University graduate student.

Recently, Dr. David Agus appeared on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart to promote his new book The End of Illness. “Why do we have such a hard time allowing science to overcome our irrationality?” Stewart asked the doctor.

While Dr. Agus had his own answer to the question, the topic is one that scholars from a range of fields have studied for several decades. In The Golem at Large: What You Should Know about Technology, Harry Collins and Trevor Pinch discuss the relationship between science and engaged publics.

In their examination of cases involving Cumbrian sheep farmers and AIDS activists in the late 1980s, Collins and Pinch argue that scientists’ hesitation (and sometimes outright unwillingness) to include public input on issues they feel belong in the scientific realm actually hinders scientific advancement.

Furthermore, when scientists’ hubris is shown to be unwarranted, as was the case of the Cumbrian sheep case in the U.K., science’s credibility is undermined among the public. Needless to say, the undermined credibility of science may contribute to the people’s inability to “overcome their irrationality.”

Iso-nope

In April 1986, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union exploded after a melt-down of its reactor’s core. As the worst nuclear accident in recent history, as Collins and Pinch describe, the incident not only killed those in the immediate accident but also “condemned many others who lived under the path of the fallout to illness and premature death or a life of waiting for a hidden enemy.”

The release of radioactive debris into the atmosphere was carried over some 4,000 kilometres to Britain. As documented in a series of studies by UK researcher Bryan Wynne, scientists in the U.K. advised sheep farmers in Cumbria to keep sheep in their valleys for fear of their exposure to radium caesium, a metal that is carcinogenic when it is unstable.

Sheep farmers became disgruntled with what they claimed were scientists’ unfamiliarity with fell farming and the land. The issue at hand concerned their livelihood and therefore it was particularly alienating when the government scientists dismissed their own expertise regarding the land. Furthermore, the farmers suspected that the danger of radio-caesium did not come from Chernobyl but rather from a nuclear accident that had occurred decades earlier at a nearby reactor.

In 1957, a reactor in the Sellafield processing plant in Cumbria caught fire and burned for three days. Many claimed the fire was never properly investigated, as details of the accident were never made public. The farmers contested that it was the Sellafield nuclear accident that was responsible for the sheep contamination. Scientists explained isotopic differences of the caesium proved otherwise. However, the scientists later recognized that most of the radioactive caesium were, in fact, from the Sellafield fire and “other sources” and less likely from the tragedy at Chernobyl.

Alternative Medicine

At around the same time of the Cumbrian sheep farmer debacle, in a continent a whole ocean away, experts and activists were contesting another area of science. The issue in this case was how to conduct clinical trials of AIDS drugs.

In April 1984, the U.S. Health and Human Services announced that the cause of AIDS had been discovered. The culprit was a retrovirus known as HIV and the development of treatments had begun. Then unlike for any other epidemic before it, a strong grassroots movement formed in the fight against AIDS. Activists were committed to learning and disseminating the truth about AIDS and how to fight it.

As chronicled by sociologist Steven Epstein, ignorance and misinformation caused AIDS to be viewed as the “gays’ disease” in the 1980s. At one point, homosexuality was also considered itself to be a disease by medical “experts.” In turn, Epstein found that the gay community was distrustful of the scientific community. With this skepticism of experts, AIDS activists sought to learn the science behind AIDS and endeavored to take the matters of treatment into their own hands.

In the meantime, Dr. Anthony Fauci and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) were charged with evaluating azidothymidine (AZT), a promising anti-viral drug in the fight against HIV. Faucui and the scientific community wanted to use traditional experimental methods when evaluating AZT. These clinical trials are made up of a test group and a control group. The test group would receive treatment and the control group would receive a placebo in order to account for psychosomatic effects of the drug that may skew the drugs’ true effectiveness. Fauci and NAIAID argued that this was the safest and only method to effectively determine the true effects of AZT.

Activists claimed two main problems with this trial procedure. The first being that the only way to measure the success of the trial was to tally the body count of each research “arm.” In other words, did the control group or the test group have the greater number of survivors? Also a cause for concern—the protocols of the studies prohibited participants from taking other potentially life-saving medications, such as those that prevented opportunistic infections. The clinical trials, activists argued, were not ethical and undermined their purpose of usefulness for the common welfare.

The activists’ distrust of “experts” spurred them to learn the science behind the controversy. The activists wanted to prove that the preferred methods of scientists were morally problematic by using their language and in the end, were successful in winning an active role in shaping drug testing procedures and protocols. For example, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was an AIDS activist group that began in the 1980s and by the 1990s found themselves included in annual International Conferences on AIDS among medical professionals that gather to discuss the status of the AIDS epidemic.

An Inconvenient Answer

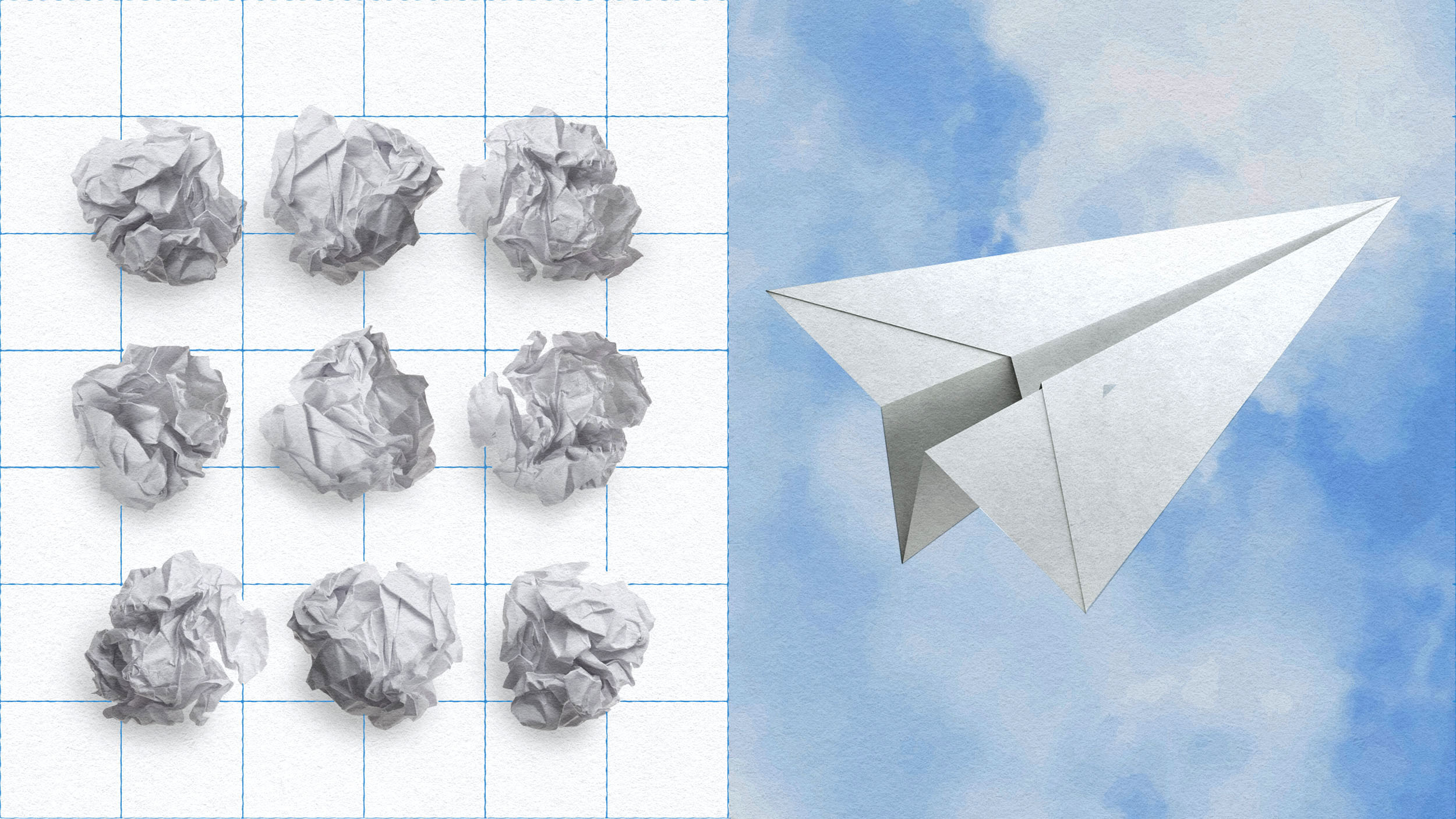

In both the instances of the Cumbrian sheep farmers and AIDS activists, we are presented with examples of the hubris of science. These were situations in which experts were reluctant at first to consider lay expertise and active public participation. In hindsight, this resistance became a hindrance to the progression of science as an institution, undermining trust among affected publics.

To answer Stewart’s earlier question, “Why do we have such a hard time allowing science to overcome our irrationality?” I would propose that the answer is that trust and communication is a two way street. When science does not properly engage the public and utilize expertise outsides its ivory walls, those affected in a debate will be far less inclined to allow science to overcome their irrationality. You can watch the interview between Stewart and physican David Agus below.

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

–Guest post by Kathrina Maramba, a MA student in Public Communication at American University. Her post is part of the course Science, the Environment, and the Media. Find out more about the MA programs in Public Communication and Political Communication as well as the Doctoral program in Communication.

REFERENCES:

Collins, M. & Pinch, T. (1998). The Golem at Large: What You Should Know About Technology. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 113-56.