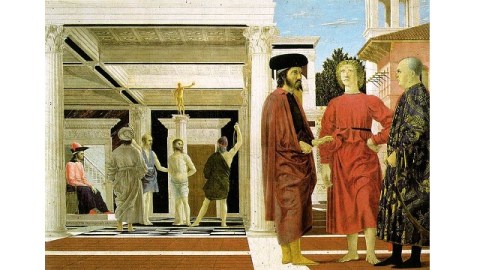

Why Is This the Greatest Living Poet’s Favorite Painting?

Poets quite often make the best art critics. The same aesthetic antennae attuned to language and meaning come into play when diving into the meaning of visual art. So, when Irish poet Seamus Heaney, 1995 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature (among a slew of other prizes), talked to More Intelligent Life magazine about his personal “seven wonders of the world,” it was interesting that he picked as his favorite work of art Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation of Christ (shown above). Called by many the greatest poet alive today and the most important poet of the last half century, Heaney knows that his pronouncements carry a lot of weight. So, why is this the greatest living poet’s favorite painting?

For an artist so connected to his native land of Ireland, Heaney reveals a startlingly cosmopolitan side in his selections. Aside from Heaney’s favorite beach, Portstewart in County Derry, “the first place where [he] encountered the ocean” that “retains for [him] the aura of original wonder and, of course, there was the mystery of the courting couples in the dunes,” Heaney’s six other wonders hail from Europe, Russia, and even America. His favorite journey trekked around the Peloponnese to “places with mythic names—Argos, Nemea, where Heracles wrestled with the lion” and Arcadia, the poet’s ultimate destination. Although Heaney calls Russia’s St. Petersburg his favorite city, he tabs the Orologio in Bologna, Italy, as his favorite hotel, the Pantheon in Rome as his favorite building, and the view of San Francisco from Grizzly Peak Boulevard as his favorite view, which gave him “a huge sense of the wonder of what man and woman have built. It was a moment of epiphany, something akin to Wordsworth’s revelation on Westminster Bridge.”

When it comes to places, Heaney spreads the wealth far and wide, seeking the monumental, yet when it comes to art, Heaney finds a whole cosmos in the tiniest image. della Francesca’s Flagellation measures a mere 23 by 32 inches, but it hits Heaney’s consciousness like a mountain. “I’m choosing a work of art that I don’t quite understand,” Heaney begins enigmatically. “If you see other representations of Christ being scourged, he is right at the front. But Piero della Francesca puts him way down at the vanishing point of the perspective, and it gives the painting an aura of the uncanny; a sense of Christian iconography, but defamiliarized. There’s a mysteriousness about it, and yet a complete clarity. I’d known it from reproductions for years, but when I first came across it in the paint—and there’s a lucent quality about the actual paint—it really made a memorable impact.”

Heaney touches upon all the standard talking points of the Flagellation: the idiosyncratic placement of the title act, the overall uncanny feel, and the tension between clarity and mysteriousness. But coming from a poet, all of those talking points take on a different significance. By choosing a work he self-admittedly doesn’t “quite understand,” Heaney shows a very poetic comfort with uncertainty. Just as poet Archibald MacLeish wrote “A poem should not mean/but be” as the standard modernist poet’s company line, Heaney adapts that modernist creed to della Francesca’s Renaissance masterpiece. Don’t try to make the painting “mean,” Heaney suggests, just let it “be,” and “be” with it yourself.

And, yet, Heaney’s restless mind can’t simply stand aside. Part of “being” with the painting as a poet is allowing your imagination to roam through the landscape of the painting, which looks to modern eyes like something out of a De Chirico painting, until you remember that the chronology (and the influence) flows in the other direction. As Heaney writes in his signature poem, “Digging,” he takes his pen and “digs” into the painting with it. The way that this five and a half century old painting still “defamiliarizes” Christian iconography for Heaney—turning over familiar ground like a spade cutting into soil—refreshes that story for the poet the way a farmer renews the earth by plowing.

Just as della Francesca digs into the familiar story of the Passion, Heaney in his brief statement digs into the familiar image from art history books and makes it fresh again. Poets such as Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and Peter Schjeldahl have always stood at the forefront of modern art criticism, so it’s no surprise that Heaney makes such a modernist, yet “old school” pick. I only wish that “Famous Seamus” would venture into art criticism more and share some more of the insights he digs up.

[Image:Piero della Francesca. The Flagellation of Christ, circa 1455–1460. Image source.]

[Many thanks to friend Dave, the second greatest living poet, for passing on this story to me.]