What Do You Do With a Sex Offender’s Art About Children?

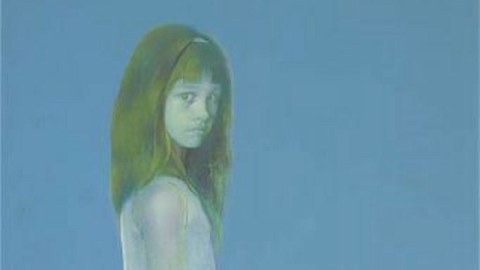

Since the Victorian invention of the modern, romantic concept of childhood, images of the innocent child have dominated Anglo-American culture and its art. Even nude images of young children that skirt the edges of child pornography often get a pass in the name of art evoking and celebrating the magical qualities of untainted youth. News of artist Graham Ovenden’s conviction on four charges of indecency with a child, two further charges of indecency, and one charge of indecent assault irrevocably taints his art that often involves images of young children, specifically prepubescent girls, such as The Picnic (detail shown above). As this Hyperallergic article by Kyle Chayka reports, the Tate Museum in England responded by physically pulling any works they own by Ovenden from public view and even removing the images from their website. Some works by the 70-year-old Ovenden date back as far as the 1960s and have beat back repeated charges of child pornography over the years, but these legal proceedings may have turned the tide permanently against Ovenden. After nearly half a century of institutional acceptance, what do you do with a sex offender’s art about children?

There’s no denying an inherent creepiness in Ovenden’s child-related art. The detail shown above from 1969’s The Picnic fails to show the full-length nudity of the young girl who challenges the viewer with her gaze and also fails to show the older man (presumably Ovenden) and a second, clothed young girl standing in the tall grass in the distance. But if creepiness were criteria for objecting to art, we’d be clearing a lot of space in our modern art museums (see, for example, Schiele, Egon). Quite often, that creepiness is a challenge to social norms. The uncomfortableness makes us think, or so the argument goes. But in the context of Ovenden’s actions, this particular creepiness now makes us think the worst. It’s possible that social norms have evolved over the past 50 years to make us more sensitive about sexual exploitation of children, but I can’t imagine a past so desensitized that such exploitation could ever be acceptable.

Chayka’s Hyperallergic article also makes a great parallel to the life and art of Charles Dodgson, aka, Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the sequel Through the Looking-Glass. Carroll’s infatuation with young girls (particularly Alice Liddell, the inspiration for the fictional “Alice”) played out disturbingly in photography. Ovenden’s a scholar of Victorian images of young children, especially those by Carroll. Carroll’s faced much posthumous criticism of his photographic fetish as a form (or perhaps an extension) of child sexual offense. Linking Carroll and Ovenden in this way may be unfair guilt by association in both directions, but Ovenden’s acknowledgment of the influence of Carroll on his art makes the connection unavoidable and the added creepiness unavoidable as well.

Just as Charles Krafft’s recent comments possibly robbed his Nazi-inspired art of any redeeming irony, does Ovenden’s conviction rob his images of any hope of being seen as a celebration of childhood innocence or, failing that, of our collective exploitation of youthful beauty in advertising and other media? Could Ovenden’s art thus be an extended visual “confession” of his own proclivities and as well as an indictment of the society that, perhaps, fed them? Are these present revelations enough to erase the art itself from our cultural memory banks?

Ovenden’s an established artist, but probably not big enough of a name to make a huge impact on the museum world. But what if a canonical artist such as Mary Cassatt, who painted multiple works showing young children in almost erotic ways (albeit often with a mother present), was revealed posthumously as a pedophile? Suddenly, the interesting undertone of a work would become the overwhelming overtone drowning out all other discussion of the painting. Would Cassatt be erased, too? I don’t know if she should or should not, and I hope we never have to even consider it. But the Ovenden case raises the always interesting question of what impact, if any, any artist’s life and actions should have on our perception of a work of art. There are certainly artistic merits to Ovenden’s paintings, as experts have long admitted, but do the moral demerits now surrounding the work trump them? Perhaps they should be allowed to be seen, if only as reminders of our obligation as a society to remain continually vigilant in the protection of our smallest, most vulnerable, and least heard members—children.

[Image:Graham Ovenden. The Picnic, 1969 (detail). Image source.]