Was There a Seventies “Sexplosion” in the Arts?

“Today, full frontal nudity is more common on cable TV than cigarette smoking is in office buildings,” writes Robert Hofler in Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange—How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos, his fascinating study of how we got to this point. Hofler contends that the American “sexual revolution” of the 1960s ignited a “sexplosion” in the arts in the half decade ranging from 1968 through 1973. In those tumultuous five years, breaking sexual taboos evolved from the counterculture to the mainstream, inspiring a sexual counter-revolution as well that still holds sway over American culture. Artists have always pushed the envelope when it came to sex, but Hofler makes a strong case that the half decade between “The Summer of Love” and Roe v. Wade represents a “big bang” we’re still feeling the vibrations of.

“Artists have been breaking sex taboos from the beginning of time,” Hofler admits, “ but probably no greater number of those totems to repression were smashed than in the year 1968… Sexplosion is the story of how a number of very talented, risk-taking rebels challenged the world’s prevailing attitudes toward sex, and, in the process, changed pop culture forever.” Hofler, an entertainment journals for four decades, experienced this “sexplosion” firsthand, initially as an admittedly fantasizing college student and later on the front lines as entertainment editor for Penthouse. Although chock full of interesting detail, Hofler never loses sight of the overall story of a powerfully liberating period of change in American arts.

The first question Hofler tackles is how the counterculture taboo breaking went mainstream. Citing the example of the popularity of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up, which featured a 2-second glimpse of female full frontal nudity, Hofler argues that “audiences were, indeed, different then… curious because they had seen and heard so little with regard to graphic sex onscreen [and] patient because they were hungry for what they hadn’t seen or heard.” Andy Warhol’s art film Chelsea Girls (a favorite of Antonioni’s) came out around the same time, breaking new ground on a smaller scale. However, major studios soon noticed the buzz surrounding these new, sexually explicit films and jumped on the “sex sells” bandwagon, perhaps not so much to liberate social mores as to make serious money, but the end result turned out to be the same. “Smashing taboos could be profitable,” Hofler points out.

Once Hofler gets rolling into his chronological progression of the “sexplosion,” the results can get a little dizzying. Crossover between media and collaborations between artists make for an incestuous storyline. “These artists knew each other,” Hofler writes, “often collaborated, and just as often competed to be first at discarding whatever the censors threw at them. In many cases, there is only one degree of separation between the novels, movies, TV shows, and plays that they created in the Sexplosion years.” For example, in just January 1968, The Boys in the Band began running Off-Broadway, a slew of sexy films were in production (Candy,Midnight Cowboy, and Barbarella), Gore Vidal’s novel Myra Breckinridge hit the shelves, and Kenneth Tynan was collecting ideas for his “sex review” Oh! Calcutta! For those unfamiliar with the history of the time, the detail can be dizzying, but I anything less would be untrue to the spirit of the age Hofler’s hoping to convey.

Hofler mixes a bit of social history into the narrative (for example, the 1969 Stonewall Riots), but his main focus is on how sexual issues played out in entertainment. Within that entertainment world, Hofler concentrates mainly on motion pictures and live theater, although he does dip into novels (how Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint discussed the self-love that dare not speak its name) and music (did Jim Morrisonreally show his penis during a Doors concert in 1969?). Anecdotes abound from these films and plays, but the most fascinating concern the actors enlisted by the writers and directors to smash taboos with their physical, mostly nude portrayals. Whereas newcomer Maria Schneider felt comfortable in her own skin (and nothing else) during the making of Last Tango in Paris, established star Marlon Brando struggled with his weight and his inhibitions. In contrast, Malcolm McDowell “turned out to be the perfect Alex in A Clockwork Orange, after establishing his comfortableness with nudity and graphic sex scenes in If…. After years of hiding his homosexuality in playing heterosexual characters, British actor Ian Bannen struggled to play the gay Dr. Hirsh in 1971’s Sunday Bloody Sunday.

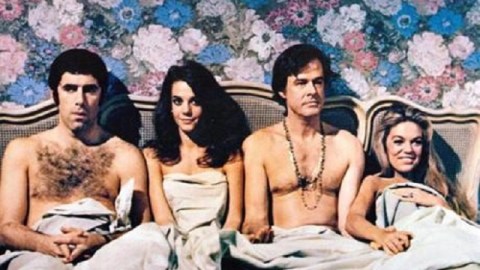

As could be guessed by the mention of Stonewall, some of the biggest taboos smashed were those concerning homosexuality. Warhol’s Chelsea Girls features as many, if not more, boys with other boys than with girls. Thanks to An American Family, one of the first reality TV shows, Lance Loud (whom Hofler calls “the Zelig of the Sexplosion years”) became “the first openly homosexual ‘character’ on television to have a story line that carried out over multiple episodes,” Hofler writes. Another boundary broken was interracial sex in everything from the controversial poster of topless African-American Jim Brown embracing topless Caucasian Raquel Welch for 100 Rifles to Melvin Van Peebles’ extended examination of male African-American sexuality colorfully titled Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Finally, heterosexual sex came out of the closet with the unbridled nudity and sexuality of plays such as Oh! Calcutta! and Hair and films such as 1969’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (whose climactic scene is shown above), which put on screen the swinging lifestyle hidden behind so many doors.

Although heterosexual and homosexual sex found a measure of freedom, it was a decidedly male brand of freedom, Hofler points out at the end. Although women participated as actresses, Hofler writes, they “were rarely instrumental in making a project happen (Jane Fonda and Natalie Wood being the possible exceptions), and there were no female executives, producers, or directors to help in those groundbreaking endeavors.” Not until books such as Nancy Friday’s My Secret Garden and Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, both published in 1973, at the tail end of the “sexplosion,” did female sexuality find its voice.

Was all this “sexplosion” just about sex (and selling sex)? Sexplosion says no through the words and actions of its heroes. When American newspaper editorials pushed back against the breaking of sexual taboos, filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, fresh off of making A Clockwork Orange, compared such attacks to Adolf Hitler’s assault on what he labeled as “degenerate art” but was really art by Jews, homosexuals, and other excluded groups. The Sexplosion happened because of the critical pressure built up over years of social, moral, and political repression. 1973 marks not only the peak of the “sexplosion” years with the APA’s dismissal of homosexuality as “abnormal” and Roe v. Wade, but also its end, and the beginning of the backlash. “[T]hose twin edicts,” Hofler argues, “functioned to galvanize conservatives, uniting them around causes to stop reproductive rights, stop gay rights, stop pornography, stop whatever else they thought contributed to a permissive society.” The “sexplosion” thus becomes the first strike in what we now know as the culture wars in America. Although we have gay marriage, legal abortion, and internet pornography today, we also have forces opposing those changes everywhere from the halls of Congress to your nearest Hobby Lobby store. Hofler sees the fact that the most recent sexually focused films (Brokeback Mountain, Shame, Crash) all came from small independent studios, in contrast to the major studio productions of the “sexplosion” era, as a sign that the forces of repression might be winning today. Or perhaps we’re going through a second “sexplosion” today and don’t realize it. If so, Robert Hofler’s Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange—How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos is history well worth reading because its history we’re living right now.

[Image: The spouse swapping scene from 1969’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice featuring Elliott Gould, Natalie Wood, Robert Culp, and Dyan Cannon.]