The Sweet, Happy Side of Philip Larkin, the Sour, Sad Poet

“They f**k you up, your mum and dad,” poet Philip Larkin wrote in the late work “This Be the Verse.” “They may not mean to, but they do./ They fill you with the faults they had/ And add some extra, just for you.” Larkin kidded that those lines would be his best remembered, a guess not too far off 30 years after his death. Where others see in those lines a perfect portrait of the sour, sad curmudgeon poet, in the new biography Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love, James Booth sees something different. “The poem’s sentiment is sad, but the poem is full of jouissance,” Booth argues. “This must bid fair to be the funniest serious English poem of the 20th century.” Likewise, Larkin — target of posthumous charges of racism, misogyny, and assorted cruelties — could lay claim to being the “funniest serious” English poet of the 20th century. Booth, who knew and worked with Larkin, shows the sweet, happy side of the sour, sad poet and makes a strong case for learning to love Larkin again, if not for the first time.

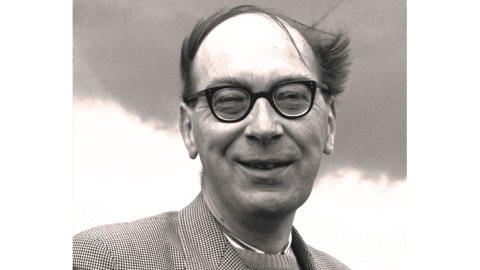

There’s an equally strong case to be made that (at least for the American edition) you can judge Booth’s biography of Larkin by its cover photo (shown above). For those who know Larkin’s poetry and the persona he carefully cultivated over the years as the no-nonsense, unsmiling public poet, the sight of Larkin relaxed and smiling at the camera, comb-over bristling in the wind like the flag of his uncovered disposition, can be a bit disconcerting. Before you even crack open the text, you’re prepared to hear about a side of Larkin rarely captured on film or ever permitted to be seen by the guarded subject.

Booth begins with an enlightening introduction that spreads all the race cards, misogyny cards, etc., on the table. Larkin famously remarked that he didn’t want “to go around pretending to be me,” but Booth sees a great deal of pretending performance art in Larkin’s life. “Some readers fail to register the performative playfulness of Larkin’s self-caricatures,” Booth defends. “These are not the words of a gaunt, emotionless failure, but of an ebullient provocateur with an instinct to entertain.” Spying the agent provocateur behind the public persona, however, is difficult for those who never knew the man, yet those who did know him, such as Booth, remember the warm, generous soul rather than the “provisional personae” that Booth sees at the root of the “various ideological Larkins” that raise critics’ hackles.

Three decades after Larkin’s death, critics still wrestle over his remains, especially the controversial letters published in 1992. A year later, an official biography, Larkin: A Writer’s Life, by Andrew Motion, one of the poet’s literary executors, made much use of what seemed to be the manipulative nature of Larkin’s correspondence to paint a negative view of Larkin that’s become the standard take for the past 20 years. Motion knew Larkin for nine years, while Booth knew him for 17, yet each man comes away with different interpretations of the poet.

Throughout Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love, Booth counters Motion’s interpretations with his own well-intended correctives. Where Motion sees Larkin’s fling with Patsy Strang as “the most happily erotic of all his affairs,” Booth rebuts that “happy eroticism had no place in Larkin’s emotional repertoire.” Later, Booth takes Motion to task for uncritically accepting hearsay from Larkin’s long-time love Monica Jones about another woman, suggesting instead that the domestic tranquility the other woman offered was “not an arrangement that a man of Larkin’s temperament could possibly have borne.” Even later, Motion sees Larkin mistreating Jones because he was “too self-absorbed to respond to her grief” and “emotionally stingy,” whereas Booth reads instead “protective sympathy … warm solicitousness, erotic tenderness, and sentimental rabbit language.” Reading Booth re-reading Motion (allegedly) misreading Larkin feels like a trip down the rabbit hole at times, but Booth keeps things civil, even praising Motion’s estimation of how Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings “transcends biography, diversifying the personal origins of poems, ‘until they become exemplary.’”

What’s exemplary about Booth’s approach to Larkin is his ability to balance a biographical reading of Larkin’s novels, poems, and letters with his personal knowledge of the man, which may still be the speculation of someone without intimate access to Larkin’s thoughts, but seemingly no one had that kind of insider access to this most private of public figures. “To some, omnivorousness of spirit will always seem a sign of deviousness and insincerity,” Booth writes of Larkin’s penchant for being a different person for different persons. “But self-contradiction is part of the human condition; and Larkin’s contradictions are central to his greatness.” To paint a less-complicated, simpler Larkin would be to do an injustice not just to the man, but also to the mission of biography itself.

In a book full of surprising insights, Booth’s chapter on “Jazz, Race and Modernism: 1961-71” caught me the most unprepared, despite knowing Larkin’s love of jazz. “Jazz allowed Larkin to indulge his longings without the censorship of reality,” Booth writes, “offer[ing] him an ideal of spontaneity and freedom” as well as “a more impersonal lesson in artistic rigour.” Booth also manages to take on charges of Larkin’s racism through Larkin’s love of jazz. Where others read racism in Larkin’s distaste for modern jazz figures such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Charles Mingus, Booth sees instead a preference for an ideal, apolitical, anti-modernist artist in the vein of Louis Armstrong, whom Larkin felt was more important than Picasso. (Larkin’s misreading of Armstrong as apolitical and anti-modernist is another matter.) Larkin admitted he disliked modernism, “whether perpetrated by [Charlie] Parker, [Ezra] Pound, or Picasso.” In the end, Larkin wasn’t a racist as much as a reactionary, a man out of step with the world changing around him.

If the opening lines of “This Be the Verse” aren’t Larkin’s virtual epitaph, then the closing lines of “An Arundel Tomb” just might be. After musing over the stone memorials of a couple dead centuries ago, Larkin concludes, “What will survive of us is love.” Many read that final line as Larkin’s romantic heart bleeding through, but Booth sees something deeper. “The poet knows that the concluding affirmation is mere rhetoric,” Booth writes, “but its ineffectuality is precisely what makes it so moving.” Any attempt to understand Philip Larkin reduces inevitably to rhetoric, which is precisely what makes Booth’s Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love so moving as a labor of love. Booth paraphrases that concluding line in his final judgment of Larkin: “What will survive of him is poetry.” My love of Larkin began in 1986 (rather late for me) between the second Reagan inauguration and Phish’s first LP, but his life and his poetry will always survive in me and all others who’ve encountered this strange, sad, inexplicably funny, and joyful soul.

[Many thanks to Bloomsbury for providing me with the image above and a review copy of James Booth’s Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love.]