Should a Death Row Inmate’s Corpse Become Art?

Because two thirds of all countries in the world have abolished the death penalty, the majority of executions happen in just five countries—China, Iran, North Korea, Yemen, and the United States of America. The idea that the state holds the power to exact the ultimate price in the name of law and order remains one of the biggest debates both internationally and within the U.S. No place in America is that debate hotter than in the state of Texas, which has executed more than a third of all prisoners killed in the U.S. since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976. One member of Texas’ death row, Travis Runnels, recently added a whole new dimension to the debate by donating his body to Danish artist Martin Martensen-Larsen’s proposed artwork, The Unifier. Martensen-Larsen plans to paint Runnels’ corpse gold (artist’s conception shown above) and pose it in a parody of Daniel Chester French‘s statue of Abraham Lincoln in The Lincoln Memorial. The Unifier could become as controversial as the death penalty it takes as its subject. Should a death row inmate’s corpse become art?

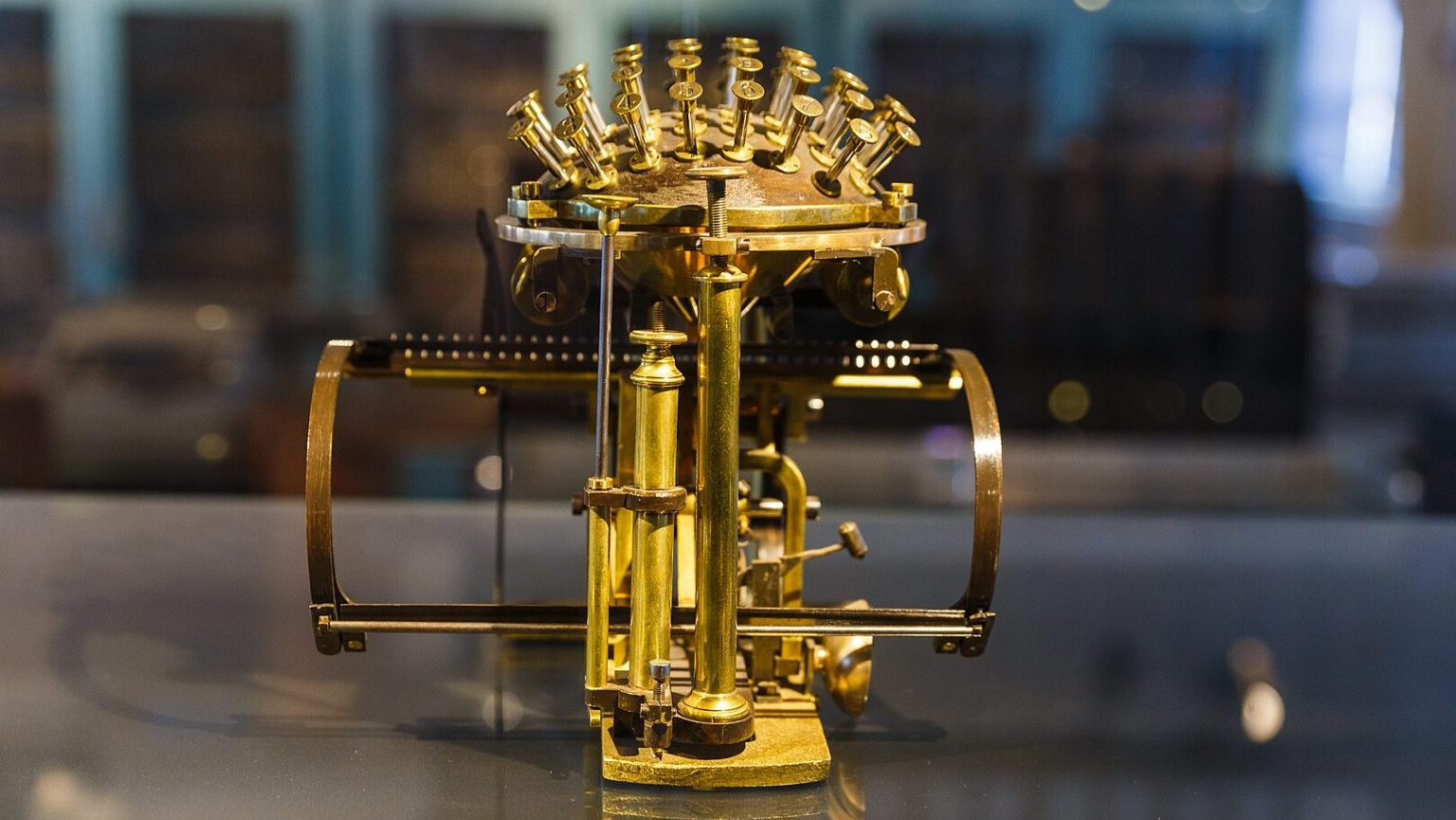

Martensen-Larsen, who actually resists the title of artist, calls himself a “jurist,” i.e., post-law degree but not yet a practicing lawyer in his native Copenhagen. The “jurist,” however, imagines The Unifier as the last third of a death penalty trilogy. In Part One, titled Curtainfall, Martensen-Larsen sold five front-row tickets to Runnels’ execution (which has not yet been scheduled). Norwegian artist Morten Viskum purchased two of the tickets, which are usually reserved for friends and family. The $12,000 raised will go to a shelter for homeless animals, per Runnels request. In Part Two, titled Redeem X, Martensen-Larsen placed the donated ashes of executed Texas death row inmate Karl Eugene Chamberlain into an hourglass. When Chamberlain’s ashes fall from one chamber to the other, the hourglass is turned over again and again. In his last words before his execution, Chamberlain wished he “could die more than once” to pay for the murder he committed, so Martensen-Larsen “grants” that final wish with the endless redemption of the hourglass.

Ashes, however, are one thing. A corpse entails entirely different moral and legal issues. Even with Runnels’ permission, Martensen-Larsen faces potential “abuse of corpse” charges if he carries out his plan for The Unifier. Gunther von Hagens’ Body Worlds’ exhibitions have toured the world since 1995, drawing crowds and criticism for its display of human and animal remains in artistic settings. An even older precedent for The Unifier is 19th century English Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s voluntarily preserved corpse, the Auto Icon. Runnels, who’s placed his own art online, might see The Unifier as his own Auto Icon in giving him posthumous fame as well as making a similar utilitarian, practical use of his death.

What exactly does Martensen-Larsen want to say with The Unifier? “Lincoln saved the union and saved the self-understood purpose of America,” Martensen-Larsen explains. “He therefore represents the Redeemer, the Unifier. The executed person redeems the blood sin of the society.” He goes on to cite the philosopher Immanuel Kant, who “said that a society that does not execute a murderer is immoral. So I will show how the death row inmate is actually one of the most valuable persons in the society, contrary to how he is portrayed in the public debate.” So, is Martensen-Larsen agreeing with those who see the death penalty as a necessary evil? Is his real problem with America’s imposing of its celebrity-mad culture even on capital punishment? Does he want to elevate the executed death row inmate to the status of religious scapegoat, literally a golden figure who assumes our sins for us?

I suspect, however, that The Unifier, however intended, will be read as anything but a unifying force. I also think that jurist Martensen-Larsen, whose native Denmark bans the death penalty, rejects any arguments supporting the death penalty, but doesn’t want the piece to be seen purely as protest. Runnels’ guilt seems unquestioned, so that’s not the issue at hand. The real issue behind The Unifier is the complex of inequalities at the heart of American legal executions: 70% of Texas death row inmates are either African-American or Latino, which reflects nationwide statistics on race and the death penalty; the mental illness of death row inmates is largely ignored; since 1976, 82% of all executions in the U.S. have taken place in the South, with 37% in Texas alone; and almost all death row inmates could not afford their own lawyer. Martensen-Larsen’s The Unifier may face “abuse of a corpse” charges, but it also raises charges of abuse of a corpse—formerly a human being—by Texas and America.