Is This What Still Life for the 21st Century Will Look Like?

Sign up for the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly newsletter featuring the biggest ideas from the smartest people

The still life, or, as the French would say, “nature morte,” died sometime around the middle of the 20th century, despite modern art’s attempts to resuscitate the genre into Cubism and Expressionism. A piece in, of all places, the “Dining and Wine” section of The New York Times, however, might be taken as proof that there’s life in the old genre yet. Mike Geno’s still lives of exotic cheeses might seem like, well, cheesy takes on a moldy old art form best left in the cupboard, but I think that, looked at in a different light, they might be just what the 21st century needs from its still lives.

I’ll forgive Jeff Gordinier, a staff writer at the Times and author of the piece, for his title, “Like the Mona Lisa, but on a Cracker.” Gordinier focuses mainly on how Geno found himself painting cheeses. (He and/or the caption editor even go so far as to call Geno a “cheese portraitist,” as if the richer cheeses were looking for something to hang over the mantelpiece.) Following a personal “larkish culinary impulse,” Geno started out painting steaks, rapidly capturing a likeness in hours so that the subject would remain edible and delicious for that evening’s dinner. From there, Geno branched out into other meats, breads, donuts, and assorted foodie fantasies (including the quintessential staple of every Philadelphian’s diet, as Philly natives Geno and I know, the soft pretzel). But cheese remained the star food item. “I only paint things that I find attractive and appetizing,” Geno tells Gordinier. “I like to translate what I find the most seductive about my subject. And cheese, it turns out, is the absolute perfect match for the way I paint. I get hungry looking at cheese.”

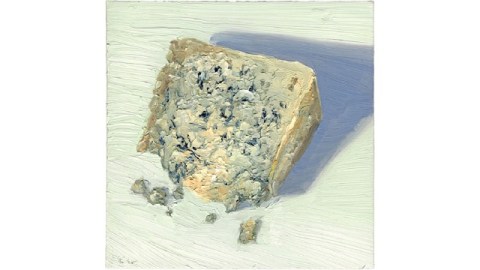

That desire comes across in the passionate brushwork and attention to detail in such works as Cabrales D.O. (shown above). Whereas Geno’s meat still lives carry on a tradition shaped by artists as diverse as Rembrandt in his Slaughtered Ox to Chaim Soutine in his Piece of Beef, I can’t recall any tradition based solely on cheese, although cheese does make the occasional guest appearance in a group still life. Like Rembrandt and Soutine, Geno picks his subject for the aesthetic pleasure of texture, line, and color. I would suggest that cheese, like meat, although less obviously, speaks of decay and death, the original theme of the “old school” still life. The French “nature morte” brings out the wonderful oxymoron of the genre when you translate it as “dead life” rather than “still life.” When you look at a cheese, you see food—the stuff of life—decaying or gravitating to the stuff of death, and, yet, in another paradox, we can eat this “death” to sustain our life. I don’t know if these ideas come into Geno’s head when he’s painting them hungrily, but I think that they’re a valid, modern interpretation of an old genre updated for the age and land of Whole Foods and Epicurious.

What makes these cheese still lives particularly modern and modern American is their internationality (another paradox). If you go to the web page for Cabrales D.O. (or any of the cheeses), you’ll find accompanying text that goes into vast, decadent detail. For Cabrales D.O. you’ll learn that it’s “[a]n intense Spanish blue cheese described by Di Bruno Bros. [a local Philadelphia specialist in specialty cheeses and meats]” as “powerful to the tongue but sophisticated and evolving. Flavors of red wine, gooseberries, dark chocolate and black walnuts all ride out a long finish that lingers on the palate.” Part education, part invitation, and part advertisement, these ready-made future museum wall panels capture the commercialism of American consumption perfectly. It’s not enough to have delicious cheese. You need to know all those details if you are to truly “experience” the cheese. Just as certain 17th century Dutchmen were fluent in the symbolism of Pieter Claesz’s Vanitas Still Life, for example, present-day Americans with means speak “Di Bruno Bros.” just as fluently.

More than just a cheese plate alternative to Wayne Thiebaud’s more well-known pie and cakes dessert menu of paintings, Mike Geno’s cheese portraits might just be the direction that 21st still lives should take if artists hope to find new relevance for a genre left behind by the wave of abstraction of Jackson Pollock and friends. If someone asks you what’s the next great subject of American art, say cheese.

[Mike Geno. Cabrales D.O. Oil on wood, 8 x 8″. Copyright Mike Geno, www.mikegeno.com]

[Many thanks to Mike Geno for providing me with the image above.]

Sign up for the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly newsletter featuring the biggest ideas from the smartest people