Is Indiana Jones Better as a Silent Movie?

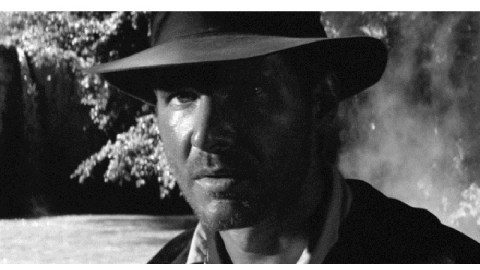

It’s one of the most unforgettable opening acts of any 20th century film. In the midst of a dense jungle, a mercenary pulls a gun on the man paying the bills in the search for buried treasure, hoping to pull a double-cross now that the payoff is near. With the crack of a bullwhip, however, the disarmed man scurries off into the jungle. The hero turns and we see for the first time the sweaty, unshaven, handsome face of Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (shown above). Raiders, as fans now call it, remains one of the highest-grossing films ever, launched the Indiana Jones film franchise, and continues to rank among the greatest action-adventure films ever made. But could it be even better as a black and white, silent movie?

Steven Soderbergh, director of Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Erin Brockovich, Traffic, and otherremarkable films, wondered what Raiders would look like if you stripped away the color, original iconic John Williams soundtrack, and audio, thus reimagining what Steven Spielberg’s 1981 film might look like if were filmed in the silent era that ended in the late 1920s. Soderbergh doesn’t specifically intend to create a silent film, claiming instead that his reimagining is a teaching tool, but that’s what he essentially ends up with—with startling results.

On his website page hosting the reconceived film, Soderbergh can’t say quickly enough that “This posting is for educational purposes only,” perhaps to avoid copyright litigation, but more honestly to justify his creation of and your close viewing of this “new,” old film. What interests Soderbergh about Raiders specifically and filmmaking in general is staging. “Of course understanding story, character, and performance are crucial to directing well,” Soderbergh explains, “but I operate under the theory a movie should work with the sound off, and under that theory, staging becomes paramount.” To prove his theory, Soderbergh turns down Raiders’ volume to turn up awareness of its imagery.

The fact that Soderbergh makes his experiment available to the public is a great opportunity for any aspiring filmmaker or anyone interested in motion pictures to learn what makes a great film great—the elusive “it” factor the uninitiated can identify with their hearts but can’t always appreciate with their heads. “So I want you to watch this movie and think only about staging,” Soderbergh instructs, “how the shots are built and laid out, what the rules of movement are, what the cutting patterns are. See if you can reproduce the thought process that resulted in these choices by asking yourself: why was each shot—whether short or long—held for that exact length of time and placed in that order? Sounds like fun, right? It actually is. To me.” As Soderbergh self-deprecatingly admits, such intense, purposeful watching might not be for anyone, but is well worth the effort.

Armed with Soderbergh’s advice, I found myself watching just the imagery, focused in my viewing in a way most of us normally are not today as we multitask on our devices as we take in our visual entertainment from television and movies, even when we’re in movie theaters. I recently wrote here about Zen and the art of silent movie watching, specifically how silent films and their dependence on visuals force us to pay attention and achieve an almost meditative state of single-minded focus on the moment on the screen before us. Even if you don’t get all Soderbergh hopes you will from his crash course in “Staging 101,” you might at the very least have an old school moment of Zen watching Soderbergh’s Raiders.

But why did Soderbergh pick Raiders? The main reason Soderbergh cites is the cinematographer, Douglas Slocombe, whose “stark, high-contrast lighting style was eye-popping regardless of medium,” praises Soderbergh. Slocombe worked on 84 feature films over the course of nearly a half century, including Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Lavender Hill Mob, before working beside Spielberg on the Indiana Jones series. Slocombe learned lighting and contrasts while working in black and white and applied those lessons even when working in color.

Another reason why Raiders works so well as a silent film could be the content. George Lucas, author of the original Indiana Jones story and producer of the films, proudly acknowledged the influence of movie serials from the 1930s and 1940s on the story. However, by Lucas’ childhood, the American movie serial was in decline from its heyday in the silent era. The Perils of Pauline, The Hazards of Helen, and four separate Tarzan serials, as well as great European silent film serials such as Fantômas, Les Vampires, and Judex represent just some of the great silent serials that created an audience for fast-paced, episodic action that continued long after the introduction of synchronized sound. Many details of Raiders can be traced to the silent era, including stunts involving hanging from trucks and other vehicles (a common Indy problem) pioneered by silent stunt man Yakima Canutt. Finally, if Harrison Ford was channeling any film predecessor in his portrayal of Indiana Jones, it was the original laughing swashbuckler—silent film star Douglas Fairbanks.

Although I realize that Soderbergh wanted to eliminate all distractions from the visuals, part of me wishes he had gone all the way into silent film territory and introduced intertitles, the dialogue and explanatory text silent film audiences sped read through. I also wish Soderbergh had forgone a soundtrack entirely instead of replacing Williams’ marches with disconcerting techno pop that made me hit mute early on. Despite these minor, understandable omissions, Soderbergh’s Raiders recreates the spirit of the silent film and raises the tantalizing question of what other films might benefit from this silent treatment. Perhaps even more revolutionary is the idea that, if fervent audiophiles can go back to vinyl for a more “human” sound, why can’t filmmakers go back to the good old days of silent films, when images and staging ruled over megamillion contracts and blockbuster special effects?

[Image credit: screen capture taken from Steven Soderbergh’s educational copy of Raiders.]