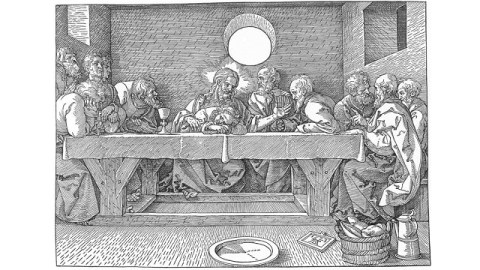

Is Albrecht Durer’s Last Supper Better Than da Vinci’s?

With Easter coming this Sunday and the minting of a new pope still fresh in people’s minds, considerations and reconsiderations of Christianity seem natural and unavoidable. The Renaissance art of the Italian big three—Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Raphael—continues to dominate the popular imagination, but a new exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, asks us to turn our eyes north, to a different kind of Renaissance man. Albrecht Dürer: Master Drawings, Watercolors, and Prints from the Albertina features all the bravura draftsmanship of Albrecht Dürer, who epitomizes what we now call the Northern Renaissance. When we think of Dürer, we think of his oversized talent matched by his oversized presence in the unforgettable portrait in which he set himself up as Christ himself. And, yet, Dürer, as the show demonstrates, could push ego aside in depicting scenes of great religious sensibility. For centuries, da Vinci’s take on The Last Supper has stood as the gold standard (even when the painting itself threatened to fall apart). Is it wrong (or even blasphemus) to ask if Dürer’s interpretation (shown above) is just as good, or even better?

You’ll be hard pressed to find more Dürer under a single roof than what the NGA is offering through June 9th. The Albertina in Vienna, Austria, boasts a veritable greatest hits of Dürer’s drawings and watercolors, including the watercolor The Great Piece of Turf, the chiaroscuro drawing The Praying Hands, and the almost obnoxiously precocious silverpoint Self-Portrait at Thirteen, which may be the youngest self-portrait drawing by any significant artist. Dürer was good, knew it, and knew it early on. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II knew Dürer was great early on, too. Rudolf II would send imperial ambassadors and pulls the levers of the machinery of state to add another Dürer to his growing collection. The crowning achievement for Rudolf II came when he acquired the collection of the Imhoff family in Nuremberg, who owned the works from Dürer’s personal estate. The emperor’s obsession allows the NGA to show off 91 Dürer watercolors and drawings and 27 related engravings and woodcuts from the Albertina in addition to 19 related drawings and prints from the the NGA’s own collection.

In addition to these well-known secular works, the show offers many of Dürer’s religious works. Like many artists of the time, Dürer enjoyed the patronage of the church and made art to sell to the sacred as well as secular market. Two “New Year’s Greeting” images designed to be distributed as woodcuts feature the Christ child as savior (in 1493) and on a donkey (in 1500). A series of pen drawings with white highlights done on green prepared paper comprise what is now known as Dürer’s “Green Passion.” These works bring out all the hustle and bustle of Dürer’s finest draftsmanship and flood the image with detail and characters. The “Green Passion” shows a passion by Dürer for the story of Christ’s suffering and death similar to his passion for mathematics found in the iconic Melencolia I (also in the show). Similarly, a woodcut showing The Death of the Virgin demonstrates a spirited approach to a familiar religious subject. Likewise, Dürer’s drawings and woodcuts concerning Adam and Eve, including The Fall of Man and The Expulsion from Paradise, resurrect the drama of the Old Testament tale.

But it’s Dürer’s woodcut of The Last Supper (shown above, from 1523) that draws me into Dürer’s religious sensibility. Whereas Leonardo wows you with the drama of the moment of the revelation of the betrayal to come in his Last Supper, Dürer picks a quieter, calmer moment of the evening’s meal. Dürer repositions St. John laying his head on the table before Christ in a lamb-like way free of all the Da Vinci Code-inspiring drama of da Vinci’s version. The room itself looks and feels simpler than the location Leonardo chose. Christ gestures simply to his left in Dürer’s version, almost visually tipping the image, already unbalanced with the food and clump of Apostles curling around the table’s end, in that direction.

Putting Dürer and da Vinci’s versions side by side, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the chalice choosing scene from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Dr. Elsa Schneider picks a jewel-encrusted chalice and hands it to villainous tycoon Walter Donovan, who drinks from it and meets his doom. Harrison Ford’s Dr. Indiana Jones then picks a humbler, more rustic cup to offer to his dying father (played by Sean Connery), who is healed by it. Beauty’s in the eye of the beholder, of course, and asking which masterpiece by a master artist is best is a dangerous and/or unfair question to ask, but I’m drawn to the life of Dürer’s work at this moment more than to da Vinci’s timeless scene. With the election of a St. Francis of Assisi-evoking, bus-riding pope in the midst of a seemingly endless global economic recession, the simplicity and rustic nature of Dürer’s woodcut feels like the more apt vision for our times.

Surrounding these religious images by Dürer are, of course, vignettes from classic mythology featuring satyrs and centaurs. A Reclining Nude from 1501 done in brush and pen with black ink, shadowed in gray wash, and highlighted in opaque white on the same green prepared paper used in the “Green Passion” seems to have travelled from the future to this show about the past until you recognize the old school draftsmanship. Agnes Dürer as Saint Ann shows the artist’s reportedly shrewish, demanding wife posing as a saint in a perhaps preparatory illustration for a larger commission, but it also shows how Dürer could bring both halves of his life together in his art. Albrecht Dürer: Master Drawings, Watercolors, and Prints from the Albertinaallows an American audience to see up close the undisputed mastery of the greatest of the German Old Masters, but it also allows the world to reconsider how this artist’s spiritual vision from the past can still matter today.

[Image:Albrecht Dürer. The Last Supper, 1523. Woodcut. Overall: 21.3 x 30.1 cm (8 3/8 x 11 7/8 in.). Overall (framed): 40.6 49.3 3.6 cm (16 19 7/16 1 7/16 in.). Albertina, Vienna.]

[Many thanks to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, for providing the image above and other press materials related to their exhibition, Albrecht Dürer: Master Drawings, Watercolors, and Prints from the Albertina, which runs through June 9, 2013.]