How We Almost Lost JFK Twice

This week we mark the loss half a century ago of President John F. Kennedy. For that generation, Kennedy’s death was the “where were you” moment. For our generation, the “where were you” moment is September 11th. In the middle of all that devastation, few knew that we “lost” JFK in that moment, too. Locked away in a safe in Five World Trade Center were 40,000 negatives of photos of the Kennedy circle by photographer and family insider Jacques Lowe. The trusted photographer of the Kennedys since the late 1950s, Lowe captured many of the iconic pictures of JFK and Camelot in the making. Thanks to the magic of modern technology, Lowe’s photographs have been restored. Those photographs, many never before published, are now united with Lowe’s recollections in The Kennedy Years: A Memoir. Lowe’s words and pictures remind us of how Kennedy became our first modern president in the sense of being the first to take full advantage of the technologies of the day to project a particular image to the public, both for personal political gain and to inspire the nation. We’ll never be able to bring Kennedy himself back to life, but Lowe’s images and recollections raise the Kennedy myth from the dead and allow us to recover the best and the brightest of that moment.

Lowe himself passed away in May 2001, just months before the terrorist attacks. He always considered his time filming the Kennedys to be his most important work, both historically and artistically. When Lowe moved back to his native Europe in 1968, he bought an extra ticket so that the negatives could sit beside him on the plane. When he returned to America in the 1980s, Lowe tried to get the negatives insured, but no company would take on the liability for those literally priceless pieces of film. Lowe finally decided to store the negatives in a safe in the seemingly secure World Trade Center Complex, close enough for him to access when needed from his studio, where he kept separately the original contact sheets and prints taken from the negatives.

When Lowe’s daughter, Thomasina, to whom Jacques entrusted the negatives, learned of the attacks on September 11th, she faced a unique dilemma: “Do I save myself or my father’s precious negatives, depicting one of the greatest statesmen of the modern era…?” “In my mind’s eye,” Thomasina writes in the preface to the book, “I could see my father running down Broadway against the flow of traffic with just one aim: to rescue his negatives. I have no doubt that he would not have paused for thought.” Thomasina chose to remain safe that day, but she’s still “haunted by the dilemma.” When the “strangely intact” safe was found in the wreckage, she discovered that the negatives inside had been destroyed. For the past 10 years, restorers using modern technology have painstakingly restored Lowe’s images from his original contact sheets and prints, which presented problems of size, scratches, dust, and Lowe’s own grease pencil markings. (A video of some of the restoration efforts can be found here.) “More than ten years after that grim day in New York,” Thomasina Lowe writes, “the publication of this book stands as a testament to the possibility of rebirth in the aftermath of almost inconceivable horror.”

Sadly, Kennedy’s assassination often overshadows the rest of his life. Lowe’s photographs allow the vigorous, youthfully alive Kennedy and his circle to shine once more by going back to the beginning, which Lowe himself fortunately found himself part of. Jacques’ relationship with the Kennedy’s actually began not with Jack, but with Bobby Kennedy. Lowe met Bobby while covering RFK’s involvement as chief counsel in the Senate committee investigating racketeering in 1957. RFK invited the freelance photographer to dinner at his home and the two struck up a friendship. During their time together, Lowe photographed RFK and his family. As a gift, Lowe presented RFK with a set of prints of those photographs. When RFK’s saw the prints, he asked Lowe to make a second set for his father, Joe, Sr. When Joe, Sr., saw the prints, he asked Lowe to photograph another of his sons then running for reelection to the Senate—Jack.

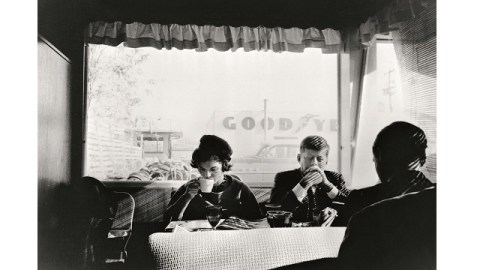

After a chilly first meeting, Lowe soon won the weary campaigner and his family over with his photographs. Working for $150 a day plus expenses, Lowe became the Kennedy’s prime image maker as the Senate reelection campaign soon became a secret (and then not so secret) campaign for the 1960 Democratic nomination for President. Lowe’s pictures capture Kennedy on the cusp of becoming “Kennedy.” The public man and master of persuading the public through pure youthful confidence and charisma seems light years away from simple images such as Lowe’s photograph of Jack and Jackie enjoying a quiet, undisturbed breakfast in a diner on the campaign trail in 1959 (shown above). While Jackie sips coffee and reads the newspaper, Jack folds his hands and muses on the day’s work ahead. Morning light penetrating the window blinds rakes across Kennedy’s hair, face, and hands, perhaps foreshadowing the larger spotlight to come. Around this same time, Lowe photographed the young couple freshly disembarked from the small plane and greeted by an underwhelming contingent of just three supporters—an image Kennedy told Lowe later was his favorite by the photographer. “Maybe nobody remembers that day,” JFK explained, “but that’s why it’s my favorite picture.” Thanks to Lowe’s pictures, we can now remember that long gone day, too, and better understand the makings not just of history, but also of mythology.

Interspersed between the memorable and new images are reproductions of Lowe’s contact sheets, the tiny proofs where the Kennedy mythos was strategically chosen. Seeing the pictures not chosen was as fascinating for me as seeing those that made the cut. Where Jackie Kennedy saw each “image [as] a piece of art… composition, light, and shadow,” Jacques writes, “Jack looked at content. For him a photograph was a document.” Fortunately for us, Jacques Lowe saw his photographs as both art and history, because his art helped shape that history in so many ways. Kennedy’s the first modern president in the sense that he’s the television president from the debates with Nixon to the short programs welcoming voters into his world, but it’s Lowe’s timeless photographs that leave the most indelible mark—time literally held still for us to appreciate and marvel over.

Lowe never hides his affection for the Kennedys in his words or his pictures. A freelancer, Lowe never needed to feign lack of bias in the name of journalism. There’s a quaintness to his prose (which was taken from talks, speeches, random writings, and family stories and edited into a chronological order) that our modern knowledge of Kennedy’s womanizing and multiple hidden illnesses make almost impossible. Lowe stopped working exclusively documenting JFK’s presidency after the first year. After the excitement of the campaign and the whirlwind tour of Europe in 1961, Lowe grew bored with the daily grind of government. Although he continued to be close with the family, Lowe learned of JFK’s assassination while in New York and rushed down to Washington in time to film the funeral. Personal anguish over RFK’s assassination in 1968 set Lowe packing for Europe, where he stayed until 1985. Amazingly, Lowe didn’t exhibit his Kennedy pictures until 1990, needing more than two decades of distance to finally let the public see his work.

In the end, Lowe often asked himself how he found himself part of history, especially why he decided to dedicate his life to documenting the Kennedys. “In Jack Kennedy and in Bobby Kennedy I had something I could believe in,” Lowe concludes, “something I could look up to, something that was bigger than me. When Jack went, we lost all that.” Through The Kennedy Years: A Memoir, Jacques Lowe’s pictures and words allow us to recover at least some of the Kennedy mystique—not for pure, blind nostalgia, as some would claim, but rather for that something “bigger” Lowe alludes to. Modern media loves to cut giants down to size, especially those who aspire to the highest offices. The Kennedy Years: A Memoir reminds us that sometimes we need giants—not to follow blindly, but as ideals (however false) to aspire to. I was born years after JFK died, but my parents filled my Irish Catholic childhood with his memory as he looked down on us in the form of a plaster bust, one of the few pieces of art my parents owned. Literally a household god for me, Kennedy’s life reminded us of all that we can achieve while his death reminded us of how little time we each have to do it. Reading The Kennedy Years: A Memoir and musing upon the pictures (none of which directly depict that terrible day in Dallas we remember this week), I found myself believing again, even in these dark economic and spiritual days for America, in bigger and better things.

[Image:Jacques Lowe. Jack and Jackie Kennedy eating breakfast in a diner on the campaign trail, 1959. © The Estate of Jacques Lowe.]

[Many thanks to Rizzoli USA for the image above and for a review copy of The Kennedy Years: A Memoir by Jacques Lowe, with a preface by Thomasina Lowe.]