How the Vorticists Defied the World (and Definition)

If the Vorticism movement had a headstone, it would confidently read “Here Lies Vorticism, 1914-1919.” Perhaps no other art movement had such a cut and dried beginning and end, yet no other art movement has been so poorly defined, even today. Great, yet slightly mad, minds such as Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound tried their best, but strayed more into mysticism than method when attempting to put Vorticist imagery into words. The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World, at the Tate Britain through September 4, 2011, attempts to make sense of the Vorticists as well as reposition them in the greater scheme of modern art. The Vorticists were rebels with a nebulous cause, but the passion of their rebellion and the art it produced still draw us into their vortex.

“In the summer of 1914, at the time of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo (28 June) and only weeks before Germany invaded Belgium (4 August), Vorticism blazed into existence in London,” begins Philip Rylands in his introduction to the show’s catalog. “During the cataclysmic years of the First World War, its flames spluttered and eventually, in 1919, winked out.” Pound came up with the name “Vorticism” early in 1914, although Lewis and others had been painting in that as-yet-unnamed style for at least a year. “The vortex is the point of maximum energy,” Pound tried to explain a few months later in the first issue of BLAST, the Vorticists’ in-house literary magazine. “It represents, in mechanics, the greatest efficiency.” What Pound seemed to be saying was that the art of this Vorticist movement captured an energy swirling all around them in the world in such a way that it became ordered and intensified. The vortex created by these artists took the blur of early 20th century life and froze it in paintings and sculptures for the edification and education of humanity.

As The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World argues, Vorticism wasn’t all that new, except in name. Taking tidbits of Cubism from the French, Expressionism from the Germans, and Futurism from the Italians, these British (and some American) artists concocted a whole new stew of their own, all while defying that they were at all like those other movements. In “Wyndham Lewis’s Vorticism: A Strange Synthesis,” Paul Edwards analyzes Lewis’ definition of Vorticism as “this strange synthesis of cultures and times (which we named Vorticism in England) and which is the first projection of a world-art, and also I think the clearest trail promising us delivery from the mechanical impasse.” As rampant nationalism in Europe ramped up for war in 1914, Lewis saw Vorticism as a way not only to bring England out of its cultural isolationism, but also to bring the scattered jigsaw of continental Europe back to some kind of reunion.

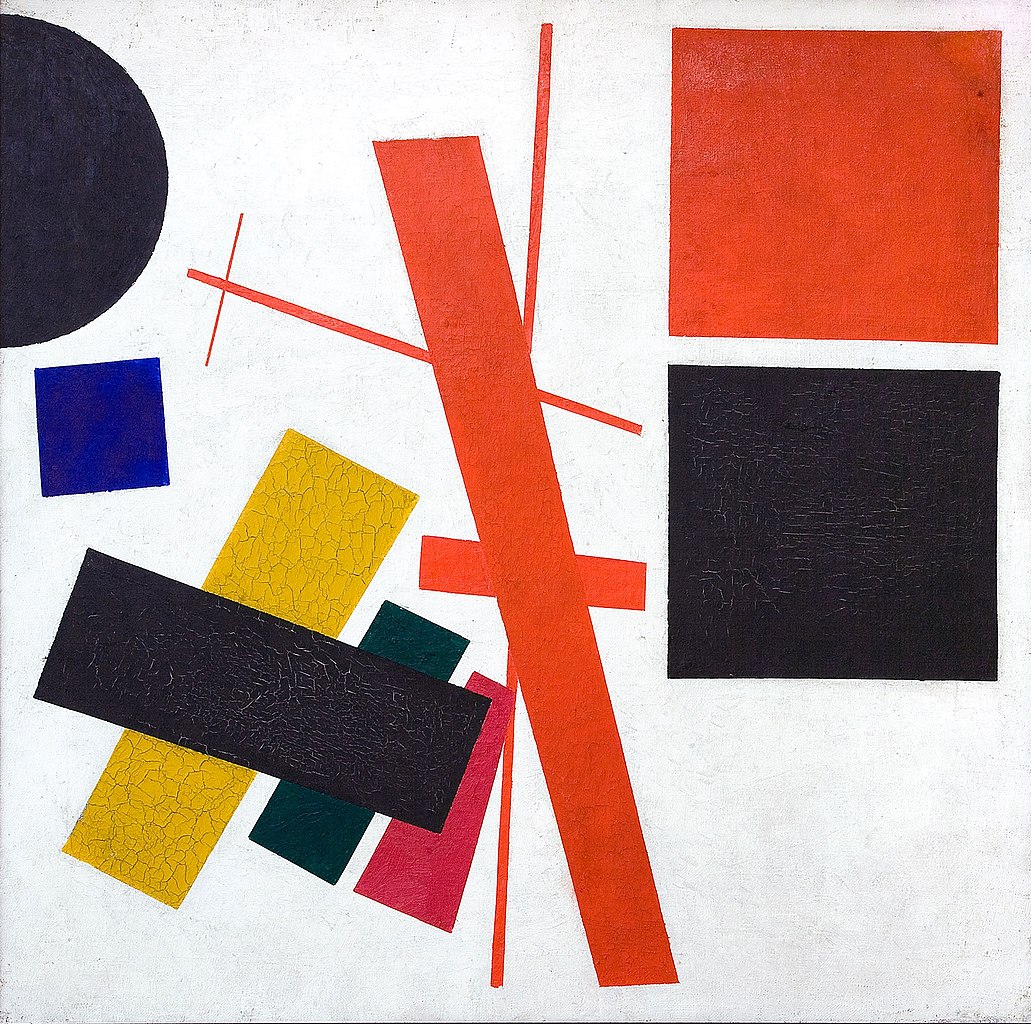

Whereas Italian Futurism cried out for war as a cleansing force, Vorticism hoped to hold war off. “The truth is that Lewis does not want his [and other Vorticist] paintings to belong exclusively to the world of matter,” Edwards continues. “Their uncompromising geometry and earthy textures evoke matter and the geometricizing intellect, but their dynamism and vibrant colours conjure spirit and transcendent intuition.” Whereas Cubism and Futurism reduced reality to solely matter, Lewis saw Vorticism as putting the ghost back into the machinery threatening to engulf Europe in bloodshed. Faced with our own seemingly endless cycle of war, perhaps we can use a little more Vorticism today, if we could only find the words to make such abstractions sing to the masses and not just the aesthetic elite.

The Tate Britain’s exhibition thoroughly and insightfully covers the short but distinguished history of Vorticism fully. Both Vorticist exhibitons—the 1915 Doré Gallery show in London and the 1917 Penguin Club show in New York City—live again in this new exhibit and ably recreate the impression that the originals once had on amused, bemused, and/or confused British and American audiences. The full range of Vorticist art appears as well, from sculptors Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein to painters William Roberts, Frederick Etchells, and Edward Wadsworth to photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn (with his “Vortographs”) to innovative typographer and graphic artist El Lissitzky (who gave BLAST its distinctive look) and even to women artists such as Jessica Dismorr, Helen Saunders, and Dorothy Shakespear.

One artist that caught my eye in this show and in the original 1915 Doré Gallery show wasn’t even a Vorticist. David Bomberg embraced Cubism and made it his own when many British artists continued to resist that and every other form of Post-Impressionism. Bomberg’s The Mud Bath (shown above, from 1914) helped establish him as one of the most innovative artists working in England at the time, a distinction that earned him an innovation to show with the Vorticists, despite his unwillingness to join in their group. Bomberg the non-Vorticist Vorticist may be the perfect example of just how ill- or un-defined this so very often defined movement was. The “manifesto for a modern world” in this exhibition’s title might be telling us that this failure of words to define an art movement may be symbolic of the 20th and 21st centuries’ astounding ability to render even the sharpest minds speechless.

“You think at once of a whirlpool,” Lewis offered in yet another attempt to explain Vorticism. “At the heart of the whirlpool is a great silent place where all the energy is concentrated, and there at the point of concentration is the Vorticist.” Regardless of how you define “energy,” you must admit that the Vorticists were as the center of something. The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World recreates that center and allows us to struggle once more with the ideas and hopes they once held. Although Vorticism fizzled in 1919, Pound continued to hammer away at the ideas behind it for the rest of his life, a strange odyssey involving giving speeches for the fascists during World War II and spending his final 12 years in a psychiatric hospital, yet still writing award-winning poetry all the while. The Vorticists were a lot of things, but they were never dull, and The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World proves that they still aren’t.

[Image:David Bomberg. The Mud Bath, 1914. © Tate.]

[Many thanks to the Tate Britain for providing me with the image above and other press materials from The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World, which runs through September 4, 2011.]