Remembering Patrick Kelly — the man who emancipated fashion

“I’ll take American Fashion History for $500, Alex.” “The answer: This man was the first American to be admitted as a member of the Chambre syndicale du prêt-à-porter des couturiers et des créateurs de mode, the prestigious French fashion association, in 1988.” “Who is Patrick Kelly?” The question remains decades later. Who is Patrick Kelly, not only the first American to join the ranks of Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, and others, but an African-American man? Two new exhibitions at the Philadelphia Museum of Art—Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love and Gerlan Jeans ♥ Patrick Kelly—try to answer that question by recalling a tragically short, but groundbreaking career in fashion in which Kelly created artful fashion while challenging racial boundaries that still persist today. Arguing against those who see fashion as trivial, Patrick Kelly’s story shows how one man emancipated fashion through fun and love.

Kelly might never have made it to Paris if not for the kindness of strangers in the shape of an anonymous one-way plane ticket to “The City of Light” given to him in 1979. (African-American supermodel Pat Cleveland, a friend of Kelly’s and an early believer in his talent, later admitted to providing the ticket to Paris, the city she fled America to after allegedly vowing not to live in the United States until a black model appeared on the cover of Vogue.) Upon arriving in Paris, Kelly made a name for himself through what he called “Fast Fashion,” ready-to-wear designs that quickly demonstrated his flair for body-conscious clothes any woman could wear, regardless of shape or age, and for fun use of colors and patterns. In an ingenious guerrilla marketing move, Kelly gave free “Fast Fashion” samples to his model friends to wear on casting calls. French Elle fashion editor Nicole Crassat noticed Kelly’s clothes on one of those casting calls, which led to a 6-page photo spread in the February 1985 that essentially launched Kelly’s Parisian and international career. Sadly, just 5 years later, Kelly would be gone.

Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love recreates the classic configuration of a runway show, with a central “stage” of outfits from More Love, the theme of Kelly’s Fall/Winter 1988-89 collection (his last), flanked by clothing from earlier shows as an “audience.” Archival footage from the runway shows appears behind the clothing, bringing the clothes to life through the original models, including the aforementioned Pat Cleveland. Add in the sounds of classic late ‘80s pop music such as Michael Jackson’s “Bad,” and you’re partying like it’s 1989. The more than 80 ensembles (recreated right down to the earrings and shoes by curators pouring over the archival footage) in the show were recently presented to the PMA as a promised gift by Kelly’s business and life partner, Bjorn Guil Amelan, and Bill T. Jones, dancer, choreographer, and Amelan’s current partner, which ensures that the museum will be the place to study Kelly for the foreseeable future.

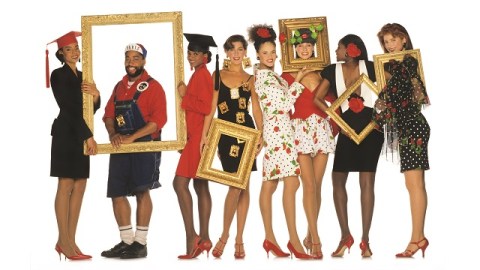

The first thing that hits you about Kelly’s art is the sheer fun of imagination, as if a big kid were designing clothes, but a precocious kid who could riff on Surrealists such as Man Ray with stacks of hats perched on models or even reframe art history itself with “Lisa Loves the Louvre” (image above), Kelly’s Spring/Summer 1989 collection that fantasized Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa inviting him to fantasize in fabric a Kelly Lisa (Patrick himself as La Joconde), a Billie (Holiday) Lisa, and even a Moona Lisa (in honor of the then 20th anniversary of the first moon landing). In addition to those whimsical influences, Kelly knew serious fashion through his study of Madame Grès, Coco Chanel, and Elsa Schiaparelli (who was perhaps his greatest influence, as demonstrated by an offhand remark that Kelly dreamed of one day calling his collections “Schiaparelli by Kelly”).

“Riff,” however, with its jazz connotations, is the wrong word for Kelly, who brought a decidedly hip hop perspective to fashion as art. As much as Kelly sampled from the world of Chanel and Schiaparelli, he also drew upon the lessons of his grandmother back in Mississippi, Ethel Rainey, whose fierce personal style inspired Kelly’s extravagant use of buttons as well as his enduring pride in his ethnic roots even on the streets and runways of Paris. Just as N.W.A owned and repurposed the “n word” through their music, Kelly owned and repurposed racial imagery such as the pickaninny, Aunt Jemima bandana, and golliwog through his fashion. (A display case in the exhibition area contains some of Kelly’s collection of dolls and other artifacts from the racist past.) Kelly even adopted the golliwog as his corporate logo, which led American stores to reject Patrick Kelly Paris shopping bags as “too controversial.” Kelly confounded the power of hate behind such images with an overdose of love, transforming the message of such caricatures from a hate crime into a shared joke everyone could laugh at. Beside a video projection of Kelly spray painting the signature heart symbol he placed on each runway backdrop of his shows stands Kelly’s professional “uniform” of oversized denim overalls, which alluded both to the African-American sharecroppers and laborers of his past as well as the hip hop artists of his present. Kelly often wore a button featuring the face of Martin Luther King, Jr., on those overalls as a reminder of the dream he, too, was striving to make true.

“Nothing Is Impossible,” reads the epitaph on Kelly’s headstone in Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris. When Kelly died on New Year’s Day 1990, friends and family cited bone marrow disease and cancer as the cause of death, rather than the stigmatizing real cause of AIDS. Even in death, Kelly (who only listed 1954 as his “approximate” year of birth to avoid ageism) resisted easy labels designed to limit him by race or sexual orientation. Breaking into the predominantly white, predominantly European world of high fashion once seemed impossible, but Kelly proved it wasn’t. Alas, Kelly’s emancipation proclamation for fashion failed to leave a larger lasting legacy. Although contemporary designers such Gerlan Marcel evoke Kelly’s spirit (as beautifully demonstrated by the accompanying exhibition Gerlan Jeans ♥ Patrick Kelly), racial boundaries in fashion stubbornly persist, as Kanye West recently pointed out in regards to his own inability to break the fashion barrier. As Alex Rees points out in that article on West, “The spring 2014 Paris Fashion Week show schedule featured 99 shows. Of those 99, not one collection came courtesy of a black designer—male or female.” Somehow, Kelly beat those long odds. Now, someone else needs to beat those odds today. To close out what was his final show, Kelly presented the obligatory “bride” look, but replaced the gown with a heart-shaped, black body suit, replaced the tiara with a candy box, and replaced the white veil with a floor-length red version—all “wrong” choices that add up to something amazingly, strikingly right. For everyone who sees fashion as trivial, Patrick Kelly in Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love shows that you can marry what many see as “wrong” (the racist imagery and attitudes still embedded in society) with a deep sense of love and pride and come up with an answer that’s not just right, but important for us all to see is right.

[Image:Patrick Kelly. Spring/Summer 1989 Collection. Photograph by Oliviero Toscani.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with a press pass to, the image above from, and other press materials related to the exhibitions Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love and Gerlan Jeans ♥ Patrick Kelly, which both run through April 27, 2014.]