How Neurocomic Gets Into Your Head

The two “go to” occupations for conveying the idea of genius are usually “rocket scientist” and “brain surgeon.” Only the best minds pursue the mysteries of the outer space beyond our atmosphere or the inner space between our ears. We all have brains, but getting our brains to understand themselves seems something reserved only for the eggiest of eggheads. Two neuroscientists, Drs. Hana Roš and Matteo Farinella, have teamed up to create the educational and entertaining graphic novel Neurocomic. By turning neurons into trees, the depths of memory into caves, and the mind’s self-deceptiveness into a haunted castle, Roš and Farinella take you on a visual and verbal rollercoaster ride into your own brain in hopes of bringing the non-brain surgeons of the world closer to cutting through all the scientific jargon and considering the big questions of brain versus mind, how we remember, and how we become who we are. A mind trip in every sense of the word, Neurocomic gets into your head to get you into your own head.

Roš, a neuroscientist with a PhD from Oxford University, and Farinella, a neuroscientist with a PhD from University College London who also is an illustrator, first teamed up on the Neurocomic project in the summer of 2012. They wanted to bring the history and science of neuroscience to a wider audience by balancing information and storytelling in a compelling yet educational way. In the “making of” film on the book’s website, Roš laments that they couldn’t get all the science into the book, but even the bare outlines of knowledge of the brain are better than nothing for the average college-educated adult.

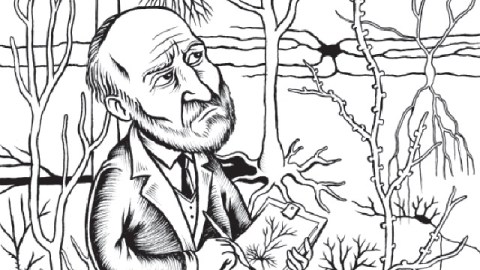

The premise of the story is that an unnamed male hero spies a lovely lady but finds himself pulled away into an alternate dimension of the mind before he can make his move. As he searches for a way out, the hero moves through a bizarre landscape as he encounters the great figures in the history of neuroscience, who explain the strange sights before him as metaphors for how the human brain works. Farinella taps into the long history of illustration in neuroscience, which had to draw what appeared under the microscope until photographic technology caught up. The story and neuroscience itself both start with Santiago Ramón y Cajal (shown above strolling through and sketching a neuron “forest”), the Spanish father of neuroscience and himself a passionate and skilled illustrator of the brain.

Roš and Farinella borrow heavily and affectionately from Lewis Carroll, Hieronymus Bosch, and (in a brief Scream cameo) Edvard Munch. The hero both falls down a hole and passes through a looking glass, all the while almost bored by the panorama before him in his singled-minded pursuit of escape. Farinella uses inventive design and interesting textures to his stark black and white illustrations to create arresting visuals on every page. Roš and Farinella’s quirky humor comes across throughout, particularly when they unleash a Kraken on a submarine manned by neuroscience pioneers Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley as revenge for their studies on squids, who have larger and more easily studied axions. Later, an oddly humanized hound tries to escape imprisonment by Ivan Pavlov only to have the ringing bell produce the famous, conditioned effect. The sloppily salivating dog manages to tell the hero to save himself between slurps. These may be the oldest neuroscience “in jokes” (only a neuroscientist would know), but they add charm to the overall surreal tone of the tale.

On the whole, Roš and Farinella manage to provide memorable visual counterparts for even the most difficult concepts, such as a banjo-strumming sea snail embodying motor memory or a speed typing sea horse for the memory-archiving hippocampus. If I found one fault with Neurocomic it was that the target audience seemed vague at times. In an attempt to cram in too much information on two facing pages, the authors sent me scurrying back and forth for a chapter or so trying to understand, which led me to wonder how well the average college-educated reader could follow. While I loved extended visual metaphors such as the haunted castle of the constructed self, I couldn’t get over the anachronism of using an old-fashioned switchboard operator surrounded by cord-dangling handsets as a metaphor for the brain’s ability to process multiple signals. Anyone in college today used to wireless iPhones would probably stare momentarily at the woman plugging wires into the switchboard and plough on perplexed. Neurocomic isn’t for kids, but maybe neuroscience isn’t for kids either.

In a mind-bending epilogue, Roš and Farinella give a nod to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics as they explain how the brain’s ability to turn images on a flat piece of paper into moving, three-dimensional stories is just one example of its marvelousness. “So, if you enjoyed this book,” the woman at the beginning of the story says at its end, “thank your brain first of all, because nothing really happened if not inside it.” As she says this while holding the hero’s hand, we see a brain-shaped projector producing their image in a theater of the mind (while Farinella sneaks in a self-portrait of himself in the director’s chair). Although Neurocomic, like any book (or even this review), happens in your head, Roš and Farinella deserve great credit for once again showing the educational value of the graphic novel to get across difficult ideas to a wider audience. Thanks to Neurocomic brain surgery doesn’t have to be rocket science anymore.

[Image: Dr. Matteo Farinella. Santiago Ramón y Cajal in Neurocomic.]

[Many thanks to Nobrow for providing me with the image above and a review copy of Neurocomic by Drs. Hana Roš and Matteo Farinella. Neurocomiccan be purchased here.]