How Art Spiegelman Is More Than Just Maus

Sometimes the toughest shadow to escape is one you cast over yourself. When artist Art Spiegelman began publishing Maus in 1980 in chapter form in the indie comics magazine Raw, which he co-founded with his wife Françoise Mouly, he couldn’t have guessed that his artistic journey into his family’s past and the Holocaust would lead to a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Spiegelman’s career stretched back to the 1960s (and Maus itself began in 1972 with a 3-page comic), but he never experienced the recognition that Maus could bring. In The Jewish Museum, New York’s new exhibition Art Spiegelman’s Co-Mix: A Retrospective, which runs through March 23, 2014, we see not only what led up to Maus, but also what’s led from it. Co-Mix is as much the story of the man who made Maus as the story of how a comic innovator and visionary escaped the snares of fame and made it out more creatively alive than ever.

Maus quickly entered the pantheon of great graphic novels quickly after its Pulitzer-ization, and rightfully so. The audacious honesty of Spiegelman’s depiction not only of the Holocaust itself, but of his parents’ own experiences and their effect on their life after the war and his childhood transcends typical historical storytelling. By using the creative conceit of casting the Nazis as cats and the Jews as mice, Spiegelman mimicked and almost mocked the less-honest, fairytale approach of Holocaust history that bled the victims dry of their individual humanity while trying to express the immensity of the horror. I’m always heartened by the appearance of Maus on high school reading lists, but that feeling’s usually tempered by my doubts at how many students and even teachers are equipped to understand the nuance and depth of Spiegelman’s images and words.

Co-Mix contains the standard “greatest hits” approach of most retrospectives, but it also takes great pains to show Spiegelman’s great pains. Through over three hundred preparatory sketches, preliminary and final drawings, prints, and other related materials, Co-Mix stresses the stress of Spiegelman’s creative process. Just as Maus was nearly two decades in the making, Spiegelman’s development as an artist spans half a century and includes everything from the revered Maus to the low-brow humor of Garbage Pail Kids. And, unlike the typical artist facing a career retrospective, Spiegelman’s career is far from over.

Spiegelman got his start in the 1960s working in the heart of the counterculture. At 15, young Art, then majoring in cartooning at New York’s High School of Art and Design, created and distributed his own fanzine, titled Blasé. By 1967, Spiegelman contributed to Wally Wood’s witzend, a proto-underground comics magazine. Around this time, underground comics became “comix,” with the “x” standing both for the x-rated sex, drugs, and violence banned from mainstream comics and for the “x” factor of unrestrained creative expression of artists free of company guidelines and free to express their opinions—political, social, and artistic—wherever and whenever they chose.

To pay the rent, Spiegelman began working as a freelancer for Topps Chewing Gum, best known for their trading cards and stickers. Eventually working his way up the corporate ladder to the status of art director and editor, Spiegelman never traded in his subversive impulses. I fondly recall the “gross out” brand of art Spiegelman helped produce to stir my Mad Magazine-fueled 1970s childhood imagination and irritate authority figures. Spiegelman’s raucous reign reached its apex with the Garbage Pail Kids, which parodied not just Cabbage Patch Kids but all forms of corporate-brand cutesiness forced onto kids to keep them quiet and unquestioning. He later wrote that the Garbage Pail Kids “were one more way to feed back the transgressive lessons I gleaned from Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad, which informed even my most serious comics work. We were trying to help another generation of juvenile delinquents come of age, to offer them a counterculture. But not one that was counter to our American Way of Life—we’re talking about the bubblegum counter. This was Topps, after all.” Spiegelman worked as a rebel with a cause—a believer in America as an ideal, if not America in actual practice.

While working creatively in the corporate world, Spiegelman never gave up being a comix artist. In 1980, he and his wife resurrected the underground comix spirit of the 1960s by founding RAW, which soon dedicated itself to introducing the work of new comix visionaries such as Chris Ware and Charles Burns to a wider audience. It’s in the pages of RAW that audiences first read chapters of Maus, which are later gathered into book form and sold in mainstream book stores as well as indie comics stores. Spiegelman had delved into personal material for years, including “Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” which told the story of his mother’s suicide, but Maus transformed the personal into the mythic—art that resonates with audiences who normally wouldn’t read “comix” or the gentler termed graphic novel. Spiegelman titled his 1977 anthology Breakdowns as pun on the technical term for a cartoonist’s panel-by-panel layout, but also to allude to his personal emotional breakdown in 1968 as well as the breaking down of psychological defenses that makes his work, especially Maus, so accessible and so compelling.

But after such a breakdown and the vast publicizing of that breakdown for Maus, Spiegelman found himself trapped by his own success. He gave up publishing longer works for years. More autobiography was absolutely out of the question. Only another epic horror—9/11—forced Spiegelman to return to the epic and the autobiographical. A native New Yorker, Spiegelman found himself first racing to reach his daughter’s school before the towers collapsed and then racing to safety with the towers’ debris at his heels. Spiegelman’s 9/11 cover for The New Yorker, which he developed in collaboration with his wife just hours after the attacks, remains the most eloquent visual commentary on that unforgettable day. The attack on his city and his family “left me reeling on that fault line where World History and Personal History collide,” Spiegelman said later. For the next few years, Spiegelman wrote and drew about his feelings and opinions about the attacks and the “War on Terror” that followed, which he eventually collected in 2004’s In the Shadow of No Towers. Even if he felt free of Maus’ shadow at last, the shadow of 9/11 quickly took its place.

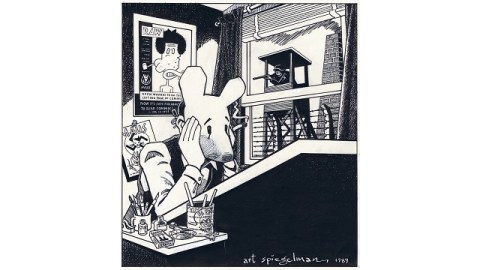

Even before the Pulitzer, Spiegelman felt the pressure of being the man behind Maus, as shown by a cover illustration he did for The Village Voice in 1989 (shown above). In that Self-Portrait with Maus Mask, Spiegelman seems flustered at the drawing board by the creation he finds himself increasingly identified by. In recent years, however, Spiegelman’s done more and more to cast off that Maus “mask” and to reclaim his place as an innovative spirit in the cartooning world. In 2010, Spiegelman fused animation with dance by collaborating with the Pilobolus dance troupe on Hapless Hooligan in “Still Moving.” Just last year, he finished a 50-foot-high stained-glass mural titled It Was Today, Only Yesterday for his alma mater, New York’s High School of Art and Design, inspired by the connection that such windows were, according to Spiegelman, “comics made before the invention of newsprint.” This year, Spiegelman teamed with jazz composer Phillip Johnston on Wordless!, which they call “a hybrid of slides, talk, and musical performance” during which Spiegelman revisits the history of the graphic novel and cartoonists who influenced his work. (Wordless!, which first debuted in Australia,premieres in New York City in January 2014.) With these multimedia works, all rooted in his cartooning past, Spiegelman looks both to his future and the future of comics (and comix) itself.

Art Spiegelman’s Co-Mix: A Retrospective takes its title from Spiegelman’s often-noted remark about his name: “Spiegel means mirror in German, so my name co-mixes languages to form a sentence: Art mirrors man.” This retrospective proves just how powerfully Spiegelman’s work not only mirrors his life in works such as Maus, but also how it mirrors the life of most 20th and 21st century Americans facing the stresses of economic uncertainty, terrorism, and increasing infringement of authority on the personal. Co-Mix shows how the “transgressive lessons” of those Garbage Pail Kids exist just as meaningfully in works ranging from Maus to Wordless! With such transgressions, Art Spiegelman slips free of the shadow of Maus and stands proudly in the spotlight as the once and future king of cartooning.

[Image:Art Spiegelman. Self-Portrait with Maus Mask. The Village Voice, cover, June 6, 1989. Ink and correction fluid on paper. Copyright © 1989 by Art Spiegelman. Used by permission of the artist and The Wylie Agency LLC.]

[Many thanks to The Jewish Museum in New York for providing me with the image above and other materials related to their exhibition Art Spiegelman’s Co-Mix: A Retrospective, which runs through March 23, 2014.]