Finding the Lighter Side of Mark Rothko

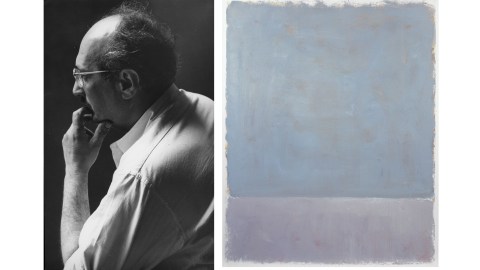

When artist Mark Rothko (shown above, left) took his own life in 1970, he forever colored perceptions of his art with that one final act. Suddenly the “classic” Rothko paintings of arranged colored shapes became suicide notes — dark messages from the dark places he painted from. Art historian and psychologist Christopher Rothko tries to paint a brighter, bigger, and more boldly human portrait of his father and his paintings in the new book Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out. Christopher Rothko takes the dark myth’s head on with humor and insight and sheds new light on the man and his art that will make you see both as you’ve never seen them before.

Christopher (shown above) was only 6 years old when he lost his father, so those hoping for a Rothko “kiss-and-tell,” “Daddy dearest” exposé will leave disappointed. Instead, Christopher wants to make his father’s art “not easier, but more directly approachable” by “indicat[ing] paths … that might have been less clear before, even as these paths remain very much the viewer’s to tread.” Christopher hopes to guide us to Mark’s paintings, but the final steps are always our own, if we are willing to face the potentially difficult truths about ourselves that the paintings often draw out.

Tapping into his own psychology background, Christopher remarks that, although people often cry before his father’s paintings, we shouldn’t assume they’re tears of sadness. “Tears do not tell us of sadness,” he writes. “They tell us a person has been moved, that they are experiencing something intensely meaningful.” This book encourages us to experience the “intensely meaningful” in Rothko’s art. Whether that meaning comes as “a most welcome gift” or “existential crisis,” Christopher explains, is up to the individual. “It’s all about you.”

As the child of Mark Rothko and (along with his sister Kate) keeper of his legacy for the last 30 years, there isn’t a Rothko joke or comparison Christopher hasn’t heard. In the chapter titled “Stacked” (strikethrough in the original), Christopher rails against critics who use easy shorthand such as the “s” word to describe his father’s paintings as “stacked” rectangles of color. (He prefers “float” instead as a way of capturing the light, rather than ponderous, effect of the arrangements.) Beginning with a college girlfriend’s description of the paintings as “big, squashy refrigerators,” Christopher counters every attempt to compare the paintings to something else (such as seeing the 1969 Untitled work shown above as a lunar surface — Rothko’s moon landing the same year as Apollo 11’s). Mark Rothko “does not want to create an ‘as if’ experience,” Christopher writes. “He wants his painting to be an experience.” Lunar landings, refrigerators, stacked boxes, etc., only get in the way of that experience, perhaps, Christopher suggests throughout, as a self-defense mechanism from the troubling truths a direct experience might present.

To show us new paths to his father’s work, Christopher reveals the misdirection of earlier approaches. These sections are where he separates the myth from the man as well as from the art. The stereotypically “classic” Rothko painting is a big canvas making a statement primarily through color, sometimes very dark color (example above). Challenging the “tyranny of size,” Christopher argues for the value of his father’s smaller works, especially the later paintings on paper when illness prevented him from working on a larger scale. Citing his father’s own stress on form over color, Christopher writes, “Color for Rothko is a means to an end, not an end in itself.” Thus, the decorative aspect of the paintings gives way to the ideas behind the arrangement of those colors in space.

Perhaps the most challenging misconception for Christopher to tackle was the portrait of his father as a dour, humorless man consumed by the bigger, cosmic questions and nothing else. Drawing from personal recollections, he recalls how his father used family as a source of “emotional fuel” for his art and cracks the code of Rothko’s subtle, sardonic sense of humor. Thus, the Rothko we think we knew — the one who painted increasingly darker paintings as he personally descended into a suicidal abyss — could paint in lighter, joyous colors even near his end (for example, the brighter work shown at the top of this post, on the right).

As great an artist as Mark Rothko was, he was an equally terrible writer, or at least an obscure, dense writer in the way philosophical thinkers quite often can be. Mark’s paintings will always do the speaking for him and his ideas. In Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out, his son finally gives him the voice he deserves — clear, thoughtful, compelling. For example, Mark writes in The Artist’s Reality (which Christopher edited), “Pictorial function of a color involves aggressions advancing or regressions coming forward or going back.” Christopher translates that Rothko-ese into “Color may be the dancer, engaging the viewer frontally with its undeniable energy, but it is kept on a deceptively tight rein by the forms that define its arena and shape its movement.” Christopher credits his father’s “economy and tempo” as keys to his art (example shown above), but the same economy and tempo drive the son’s artful, accessible prose.

Critics can often overpower Rothko’s art, giving us another “as if” blocking the path to experiencing the paintings themselves. For example, Simon Schama’s final paean to Rothko in his Power of Art series (“womb, tomb, and everything in between”) gets us closer to Rothko, but Schama still gets in the way, even when he’s wonderfully right. Issuing a complaint similar to Christopher Rothko’s, Schama also says in that documentary, “I thought a visit to the Seagram Paintings would be like a trip to the cemetery of abstraction — all dutiful reverence, a dead end.” As Schama realized (and Christopher Rothko points out), the real “dead end” is the issue of Rothko’s suicide, which distracts us from looking at his art with the clear eyes and open heart he intended them to be seen with.

“You may officially consider your mindset under attack,” Christopher Rothko announces in his fight specifically against “the tyranny of size” that leads people to underestimate his father’s smaller works. Actually, all of Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out attacks the typical mindset even the most well-intentioned have when approaching Mark Rothko’s work. Christopher Rothko sees not just the tyranny of size, but also the tyranny of biography hindering people from encountering his father’s work fully. “Writing about the Rothko Chapel,” Christopher explains, “is not so much an exercise in futility; it is simply beside the point.” All writing about Mark Rothko ends up being “simply beside the point,” but Christopher Rothko’s writing about Mark Rothko reminds us in words just how pointless words can be. Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out may be the finest book on Rothko I’ve ever read for this simple point about how the words, myths, and metaphors push us further away from the art and, more importantly, further away from discovering things about ourselves that only such naked encounters with art can make possible.