Does Opera Have a Weight Problem (But Just for Women)?

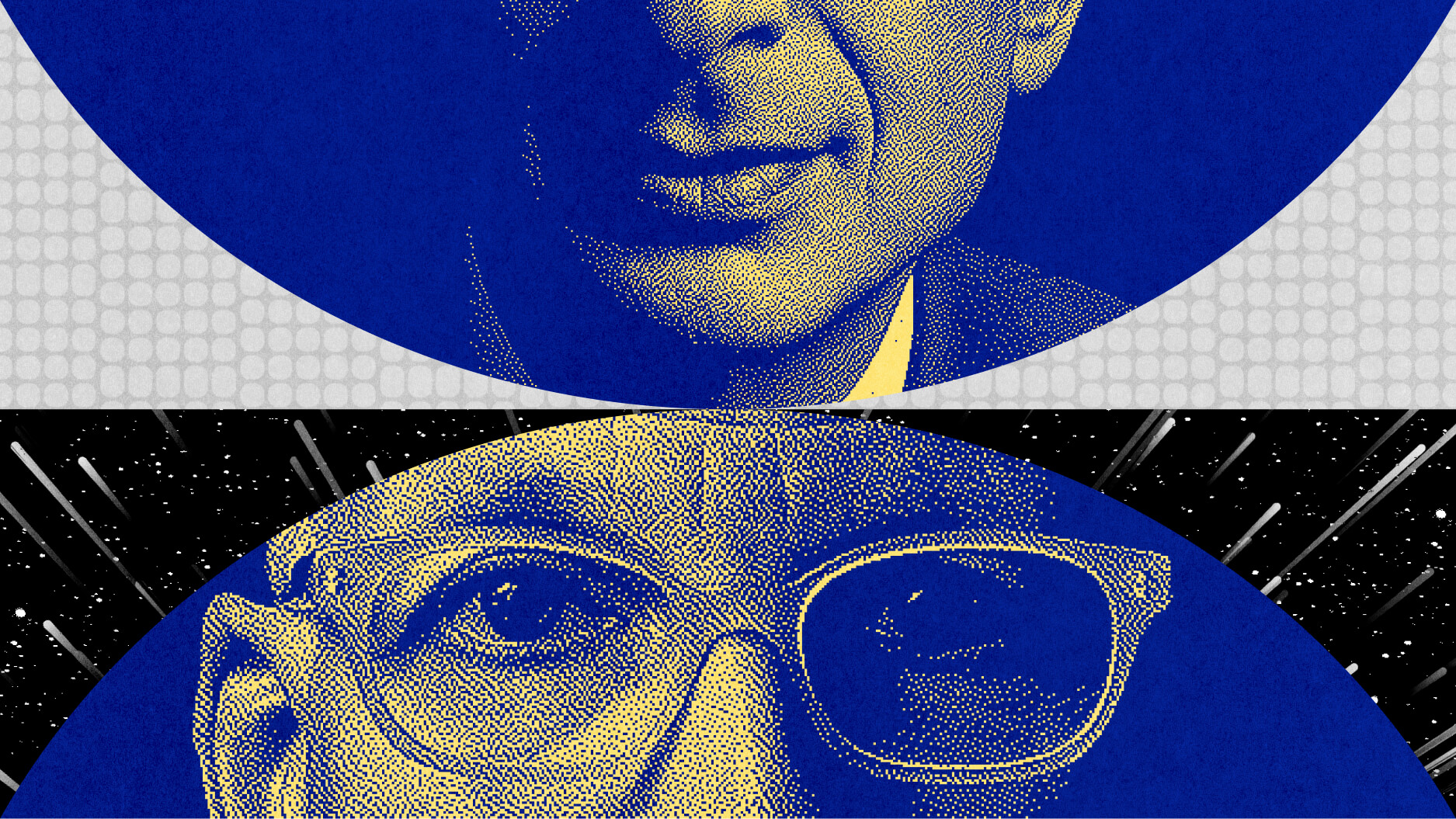

“It ain’t over till the fat lady sings.” American sport fans have heard that Wagnerian opera allusion countless times when one team seems hopelessly behind but with plenty of time to come back. Unfortunately, the stereotype of overweight opera singers, specifically women opera singers, reared its ugly head once again in an incident involving 27-year-old, Irish mezzo-soprano Tara Eerraught (shown above) singing the part of Octavian in Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier at this year’s Glyndebourne Festival Opera in England. Early reviews from several major British newspapers all focused on Eerraught’s physical appearance and how they felt her weight detracted from the quality of the performance. Witnessing this young singer face age-old stereotypes about body image, the opera world took arms against the critics to bring the curtain down once and for all on opera and modern society’s female-specific weight problem.

Sadly, nobody has any problem with Eerraught’s voice. (Listen to her sing “Una voce poca fa” from Gioachino Rossini’s The Barber of Sevillehere.) Even most of the weight-watching critics acknowledge her singing talent. Yet, they oddly can’t get past the packaging of that talent. The Telegraph’s Rupert Christiansen calls Eerraught “dumpy of stature” and the possessor of an “intractable physique.”The Guardian’s Andrew Clements went with “stocky” while questioning Eerraught’s plausibility as a lover. The Independent’s Michael Church labeled the singer “a scullery-maid” while saying nary a word about her singing one of the main parts in the opera. The Financial Times’ Andrew Clark got cute and canine in calling her “a chubby bundle of puppy-fat.” Finally, The Times of London’s Richard Morrison doesn’t mince words in condemning her as “unbelievable, unsightly and unappealing.” This fat-shaming five have, at least to my knowledge, failed to apologize. In fact, The Telegraph’s Christiansen doubled down by announcing that he still “stand[s] by every word.”

It’s no surprise that the five critics are all men, as this weight issue seems to be aimed mainly at women in opera, just as it is in society at large. Mezzo-soprano Alice Cootepublished an open letter to these critics on the music website SlippedDisc.com challenging them and fans to get past the surfaces to the artistry beneath. “It is not about lights, it is not about costumes, it’s not about sets, it’s not even about sex or stature,” Coote implores. “It is ALL about the human voice. This is the Olympics of the human larynx attached to a heart and mind that wants to communicate to other hearts and minds… All the visual messages that a production and costume brings to an opera does not alter (even though they can try very hard) the fact that it’s true success in moving and making an audience love the Art form lies in the voice that sails across the pit to the audience and into their ears.” Audiences, Coote continues, “are not moved by seeing a conventionally beautiful or attractive person walking around in a lovely or impressive costume or lights or environ. This they can get in the theatre (although I doubt that moves them much either) or in film or in daily life. Opera is NOT about that. It is about and really ONLY about communication through great singing.” Coote even contends that the ripped abdominals of idealized physical beauty might actually rob an opera singer of the flexibility necessary to sing at such an Olympian level.

Coote’s blast at the ab blasters and their supporters on the opera stage includes the obvious example of Luciano Pavarotti who, Coote writes, “stood on stages and sang audiences into near hysteria” in becoming “the most famous classical singer of our time.” Where were the fat shamers when the aging, balding, overweight Italian played the lover in countless roles, often visibly sweating under the strain in later years? Was that any less plausible than Eerraught’s playing the lover? When I look at Eerraught I see an attractive young woman of average build, not the grotesque, almost morbidly obese monster these critics paint her to be.

Coote brings up the interesting point that audiences looking for aesthetically pleasing bodies and faces can find them elsewhere. Why, then, are the critics looking for them in opera, of all places? Is this how opera—an increasingly marginalized art form—hopes to go mainstream? It reminds me of classical music’s often odd use of female sexuality on album covers. The classic example of classical music sexploitation is violinist Lara St. John’s album of Bach violin solo pieces on which she appears topless save for her strategically placed instrument. (Sadly, St. John’s revealing cover made her recording a best seller by classical standards, thus reinforcing all the wrong ideas about women and music.) Do women have to be attractive to get noticed even in the classical/opera music world today, which should be more of meritocracy than popular music has ever been or can ever hope to be? What happens when even that last door is closed?

Maybe this controversy is a blessing in disguise in bringing this dark side of opera and music criticism into the spotlight. Maybe it will inspire a wider audience to watch Tara Eerraught’s performance in Der Rosenkavalier and judge for themselves. (The Telegraph will stream a performance of the opera on their site on June 8th.) But maybe this episode will inspire some young woman to express herself artistically on a stage without first judging herself by her physical appearance because she no longer needs to fear others closing their ears and minds simply because they don’t like what they see.

[Image: Irish mezzo-soprano Tara Eerraught. Credit: Christian Kaufmann. Courtesy of IMG Artists.]