Do We Show Our Real Selves While Sleeping?

“Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed/ The dear repose for limbs with travel tired,” William Shakespeare writes in his Sonnet 27. “But then begins a journey in my head/ To work my mind, when body’s work’s expir’d.” Shakespeare knew well that the mind took a journey when the body’s trek through the day ended, but he was wrong about the “body’s work[] expir[ing]” at bedtime. We spend a third of our lives asleep and we shift about for much of that time, as modern sleep study has proven. Researchers now regularly photograph their slumbering subjects, but photographer Ted Spagna pioneered the practice, even before he began partnering with scientists interested in using his images. In Sleep, Spagna’s photographs of himself, family, and friends reveal the hidden world of sleep to satisfy the scientifically curious, but also to enthrall those who recognize the narrative quality of the series of pictures taken throughout the night as well as the penetrating insights of portraits taken when we are at our most vulnerable and, perhaps, most ourselves.

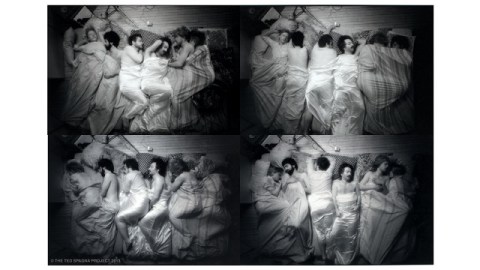

The first person Spagna photographed asleep was himself. Setting up a camera above the bed to look down from what he called a “God’s-eye view,” Spagna used a timing device called an intervalometer to take between 20 and 30 photographs at 15-minute intervals throughout the night. Spagna, a beloved teacher and filmmaker in addition to an innovative photographer, then put the individual images together to capture what he called “the architecture of sleep.” From 1975 until his death in 1989, Spagna continually pushed the envelope with his sleep portraits, moving on from self-portraits, to individual portraits of family and friends, to portraits of couples, to portraits of groups, and even to portraits of sleeping animals. Schizophrenics, sleepwalkers, and even spacewalkers on the space shuttle were next on Spagna’s list when he died at the age of 45. Spagna’s initial discover of “a whole other person” in his sleep self-portraits continually spurred him on to reveal the whole other people for others that only emerges during sleep.

Sleep specialist Dr. Allan Hobson credits Spagna with introducing the idea of photography to sleep studies. “Whether or not Spagna’s sleep portraits capture a hidden self,” Hobson writes cautiously, “they are unquestionably surprising in their revelations of sleep as behavior—especially the tenderness of sleeping couples—and they are unquestionably visually rich.” What Eadweard Muybridge is to early photographic studies of humans and animals in motion, Hobson suggests, Spagna is to late 20th century photographic studies of humans and animals at rest (or restlessness). If nothing else, Spagna and his work prove that art and science can work together without diminishing each other in some way.

But aside from their scientific value, Spagna’s photographs hold great aesthetic value. In the foreword to Sleep, photographer Mary Ellen Mark muses on Spagna’s achievement. “[S]o touching and personal, so real and caring about humanity,” Spagna’s photos are for Mark perfect examples of how “[d]ocumentary photographers strive for total access and the opportunity to capture reality, truth, and intimacy.” Ultimately, Spagna’s project is all about trust. Spagna’s subjects trusted him enough to allow them not just into their bedrooms, but into the most personally vulnerable span of their existence. It helps that many of Spagna’s friends turned subjects were artists themselves and perhaps more willing than the average person to open themselves up to such a self-revealing experience.

When a group of Spagna’s artist friends gathered together in 1980 at the University of Vermont to see an exhibition by a mutual friend, they allowed Spagna to film them in a group sleep portrait he later titled The Wave of Sleep (detail shown above). The six friends—four men and two women—change positions from image to image, but always remain linked. Mark likens them to a row of puppies cuddling together, but the black and white nature of the images made me think more of a Greecian frieze as the individuals seem to dance across a stage, with the bedclothes almost rippling in a nonexistent breeze. No smiling group photo of these people awake could capture the unspoken, unconscious bond between them the way that these photographs do.

Similarly, the sleep portrait of middle-aged husband and wife titled The Prokops defines their bond in a way that waking, more guarded portraits cannot. In contrast, a portrait of an individual, such as aging Uncle Artie, powerfully and almost painfully captures the loneliness of the solitary sleeper. Many of the photos are in color, which captures the rhythms and patters of the bedsheets and blankets as well as the movements and choreography of the sleepers. In Mr. and Mrs. Dream Doctor, the bright red waves on the pillowcases add to the sense of movement as the couple spoons from side to side through the night. Many of the sleepers sleep in the nude, adding to the voyeuristic quality of looking at these pictures, but, again, the dance-like aspect of the photos transforms them into almost classical nudes, timeless in their pure, unmasked humanity.

Perhaps the most fascinating sleep portrait is Spagna’s own self-portrait from 1980. Several still lives of stacked pastel pillows and dark navy sheet suddenly give way to a frame of frenzied activity—Spagna and guest share a joint whose flame inscribes a bright signature on the exposed film. A few frames follow the blurry forms of the twosome in an intimate moment before the bed is once more emptied. Spagna returns, alone, to sleep the rest of the night away, pulling pillows into his embrace, perhaps dreaming of the partner who slipped away. In the final row of pictures, the light changes noticeably as the sun rises and fills the room. When Mark says that looking at one of Spagna’s sleep portraits is akin to “reading a great novel or watching a great film,” it’s series such as that self-portrait that exemplify the complex, nuanced storytelling Spagna’s photography contains.

“Colleagues ask me if I ever tire from having made the same photographs for so long,” Spagna remarked in 1986 after a decade of sleep portraits. “My excitement and interest in the work has increased rather than waned. I never tire at looking at the work. Each portrait is an entirely new exploration, and the information it contains completely unique.” It’s this tireless pursuit of the unique that makes Sleep such a fascinating and beautifully humanistic work (even when it shows animals at sleep). Ted Spagna recognized a hidden self on display only while sleeping and challenged others to open up to his camera to show that side to the world and, more importantly, to themselves. Spagna’s Sleep does, indeed, demonstrate what art and science can accomplish when they join forces, but it most importantly demonstrates that both art and science serve the same goal in furthering human understanding, that even “hard” science has a soft, aesthetic side where beauty can reside.

[Image:Ted Spagna. Wave of Sleep, 1980 (detail). Images courtesy of George Eastman House and © The Ted Spagna Project 2013.]

[Many thanks to Rizzoli USA for providing me with a review copy of Sleep, photographs by Ted Spagna, edited by Delia Bonfilio and Ron Eldridge, text by Allan Hobson, MD, foreword by Mary Ellen Mark. Many thanks also to George Eastman House and The Ted Spagna Project for providing me with the image above.]