Can a 19th Century British Art Movement Solve the Modern Global Jobs Problem?

“Workers of the world, unite!”Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels bellowed in The Communist Manifesto in 1848, largely in response to the Industrial Revolution (and Second Industrial Revolution) threatening not just the livelihoods but the very lives of many workers as profit reigned mercilessly over people. Marx even put the slogan on his tombstone, long before the Soviet Union adopted it as their official mantra. Workers of the world today facing the double whammy of technological revolution and systemic economic collapse wonder what, if anything, they should unite around. Although she doesn’t take the idea as far as I’d like to, Yvonne Roberts in The Guardianoffers a possible solution in 19th century British artist and designer William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris “esteemed craftsmen and women, unlike today when they are seen are second-besters,” Roberts writes, but I think you can extend that “second-best” label to nearly all the “99%” facing underemployment or non-employment around the world. Can a 19th century British art movement solve the modern global jobs problem?

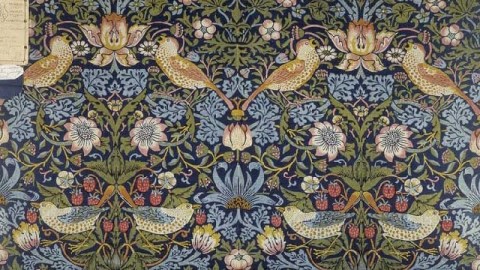

Roberts neatly juxtaposes Morris’ view of work and workers with the prevailing view today. Morris (whose The Strawberry Thief textile appears above) was “a passionate advocate of what’s much missed today, the pleasure (and pain) of the handmade and the value of the vocational,” but “[t]oday, snobbery dictates that those who earn a living with their hands are seen as academically inferior, dim second-besters.” Roberts asks all to “come out of the mass-produced closet and acknowledge that, perhaps we wouldn’t be facing such a famine of engineers, inventors and makers” if we honored the job worker as much as the self-proclaimed “job creators.”

Morris specifically talked about craftspeople because that was the situation his generation faced. Today, the stigma of work extends beyond just craftspeople to almost all jobs. Paul Krugman’s recent New York Times editorial, “Sympathy For The Luddites,” also harked back to the dark days of the Industrial Revolution. “[O]ften the workers hurt most were those who had, with effort, acquired valuable skills—only to find those skills suddenly devalued,” Krugman writes. “So are we living in another such era? And, if we are, what are we going to do about it?” Answering his own questions as well as long-standing arguments for the unalloyed benefits of technological advances, Krugman argues that “[t]oday, however, a much darker picture of the effects of technology on labor is emerging. In this picture, highly educated workers are as likely as less educated workers to find themselves displaced and devalued, and pushing for more education may create as many problems as it solves.” Even the deeply rooted faith in education as a solution to obsolescence—de-ludding the luddites—no longer applies in the 21st century global economy.

Krugman suggests that “the only way we could have anything resembling a middle-class society — a society in which ordinary citizens have a reasonable assurance of maintaining a decent life as long as they work hard and play by the rules — would be by having a strong social safety net, one that guarantees not just health care but a minimum income, too.” To those who would call that scheme ”redistribution” or, more heatedly, Marxist socialism, Krugman wonders “what, exactly, would they propose instead?”

Another solution might be to simply change the way that work itself is viewed. Just to take the American example, work itself has been devalued steadily for the past three decades, while the financial sector has become the domain of the “masters of the universe.” Unions and other worker advocacy organizations have become demonized in the press and political discourse. Meanwhile, the economic gap between the working middle class and the upper ownership class has rapidly expanded, in large part thanks to the revised tax structure. Scroll down and look at this chart recently released by the Economic Policy Institute. The dark blue line at top shows the actual gap. The light blue line at the bottom shows what the gap would look like if tax rates had remained at 1979 levels. The gap between the gaps demonstrates that just as the ownership class reaped record rewards, the tax structure allowed them to keep more and more, all at the expense of the middle class that had to shoulder more of the load.

How can the modern worker be respected (or respect herself) in such a situation? Roberts picks a good quote from Morris that might offer a solution. “”A good way to rid one’s self of a sense of discomfort [or, for the modern worker, disillusionment] is to do something. That uneasy, dissatisfied feeling is actual force vibrating out of order,” Morris said. The “force vibrating out of order” today seems to be the global economy itself, which now serves the good of the few over the good of the many. The Arts and Crafts Movement blunted some of the bedeviling power of what William Blake called the “dark Satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution. Perhaps it could inspire today’s working class to cast out the demons of inequality and erase the devils in the details of the tax code.

[Image: William Morris.The Strawberry Thief, 1883. Textile design for walls or furnishings.]

[ANNOUNCEMENT: I will be presenting a lecture titled “Art Made Personal: Chris Sanderson and the Wyeth Family” at the Christian C. Sanderson Museum in Chadds Ford, PA, on Sunday, June 23rd, from 1 to 3 pm. Please come out to support a great museum with a great collection of art and historical artifacts.]